Sharing the cockpit

10 ways to annoy your right-seat pilot

Whether a turbine aircraft requires two-crew operations or not, cultivating a good relationship with the person in the seat next to you pays dividends. As a service to captains and crews of general aviation turbine airplanes, here is a list of ways in which pilots in command can annoy their right-seaters, whether they are bona fide first officers or “co-crew” pilots helping out in single-pilot operations. These habits range from mildly annoying to dangerous.

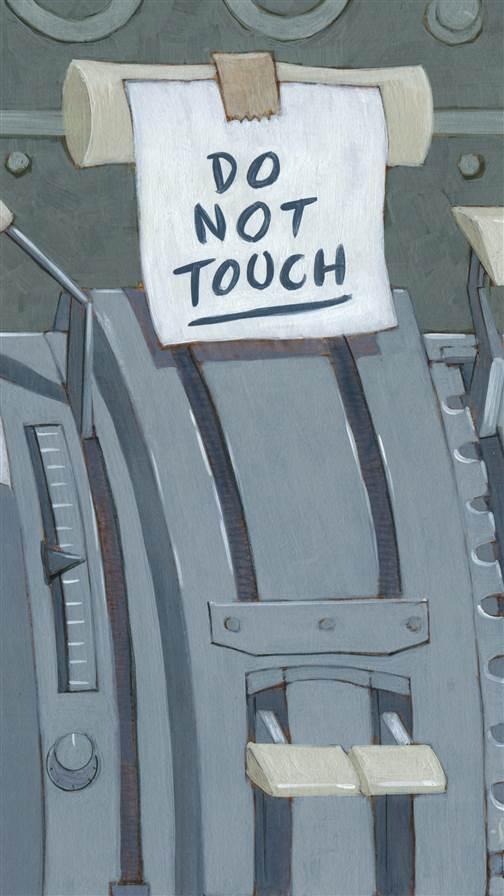

1. Keeping your hand on the flap handle. Many captains have the habit of putting their hand on the flap handle during approaches when they are not the flying pilot. I’ve never been sure if this is a hint to call for the flaps or if they are reminding themselves not to forget them. Either way, I found the habit annoying and would sometimes delay calling for the flaps just to make them keep their hand there.

The best way to remember to put the flaps down is to use the landing checklist. If you make a habit of running the checklist correctly before landing, you won’t forget the flaps. If you think the flying pilot has forgotten a checklist item, just ask.

2. Starting a radio conversation and expecting your co-pilot to finish it. When two pilots share responsibilities in the cockpit, the pilot flying typically does not talk on the radio. However, sometimes workload is high and the pilot monitoring is doing something else or misses a call. At certain times, it might be easier or more efficient for the captain to just make a transmission him- or herself. That’s understandable. But if you do make a radio call, finish the exchange. Don’t just stop in mid-conversation and expect the right-seater to pick up where you left off.

Whether you have a formal dispatch release or print your flight plan and weather from a flight-planning website, the first officer needs to have access to it.An even better solution is to let the pilot not flying do his job as the person communicating with ATC. If time permits, tell him what you need and let him make the transmission. This has the added benefit of keeping both pilots involved in the decision-making process.

3. Trying to do his job. A two-person crew is a team, and each crewmember has a role to play. When the captain tries to play both roles, it causes problems. At most companies, each crewmember has specific duties arranged in a flow. The pilot flying generally should not touch anything not related to controlling the airplane. Other tasks, from selecting the altitude to raising the flaps and setting radio frequencies, are assigned to the pilot monitoring. If the pilot flying tries to do these “housekeeping” tasks as well as fly the airplane, it disrupts the flow of the nonflying pilot. More important, it takes the flying pilot’s attention away from control of the airplane.

4. Using nonstandard procedures. First officers at large companies fly with a lot of captains. Make your first officer’s life easier and fly the way the company wants you to fly. A first officer shouldn’t have to be a chameleon who adapts to the style of every captain. Your company wants you to fly a certain way for a reason—normally, this is because it’s safer than making up your own procedures.

5. Hogging the paperwork. Whether you have a formal dispatch release or print your flight plan and weather from a flight-planning website, the first officer needs to have access to it. Some captains guard these vital flight documents as if they contain personal secrets. Part of a first officer’s job is to back up the captain, and he can’t do that if he doesn’t have all the information. If you want your first officer to make sure the aircraft is properly fueled, he needs to know the fuel burn for the flight. Plus, it’s never a bad idea to have two sets of eyes on pertinent details of the trip, such as the weather, notams, and any special instructions pertaining to departure and arrival procedures.

5. Hogging the paperwork. Whether you have a formal dispatch release or print your flight plan and weather from a flight-planning website, the first officer needs to have access to it. Some captains guard these vital flight documents as if they contain personal secrets. Part of a first officer’s job is to back up the captain, and he can’t do that if he doesn’t have all the information. If you want your first officer to make sure the aircraft is properly fueled, he needs to know the fuel burn for the flight. Plus, it’s never a bad idea to have two sets of eyes on pertinent details of the trip, such as the weather, notams, and any special instructions pertaining to departure and arrival procedures.

6. Not keeping him in the loop. Exercise cockpit courtesy and let the other crewmember know what you’re doing. The other pilot needs to know if you turn the anti-ice on or the seatbelt sign off. Make sure you both see the airport and the traffic before calling it in sight.

There are legitimate reasons to deviate from standard procedures, but if you are going to do so, brief it before you do it. For example, if you plan to take off with a different flap setting or delay gear retraction or extension, the other pilot needs to know your plan. Otherwise, he’s going to sit there wondering what you’re doing.

7. Never letting him fly. Your first officer is a qualified pilot. If he wasn’t, he wouldn’t be there. And if you’re using a type-rated co-pilot to help out in single-pilot airplane operations, that person also needs to stay sharp. Keep in mind that flying skills are perishable and everybody needs to exercise them to remain competent.

Sharing duties gives everybody in the cockpit a break—as well as flying practice.At most airlines, the custom is to trade legs. The two pilots alternate between flying and monitoring roles so that both maintain their skills. The same can be practiced in situations where a single-pilot-certified left-seater is helped out by a type-rated co-pilot. There may be exceptions when it’s a low-time co-pilot, but sharing duties gives everybody in the cockpit a break—as well as flying practice.

8. Acting like a check airman. Flying shouldn’t be a daily checkride. If you aren’t a check airman, then you shouldn’t be attempting to administer an oral exam to your co-pilot. There is no better way to add tension to a cockpit than to start quizzes about memory items and limitations that have nothing to do with the situation at hand.

9. Shutting him down. A basic principle of crew resource management is keeping lines of communication open. Intimidating and insulting your co-pilot into silence inhibits communication. The accident files are replete with right-seaters who didn’t speak up in accident scenarios.

If you want your co-pilot to be confident enough to speak up and prevent an accident or incident, you should start by letting him or her know that you value his input from the first day that you fly together. Once a crewmember has been shut down, the damage is difficult to repair.

10. Losing trust. The worst thing a pilot can do is lose the trust and respect of the crew. Everyone makes mistakes, but if the pilot flying consistently puts the crew in danger, the crew will start second-guessing his or her actions to protect themselves. If it gets bad enough, they may start refusing to fly with that pilot.

To keep the trust of your crew, stay proficient and knowledgeable. Brief departures, approaches, and arrivals before you fly them. Keep yourself up to date on aircraft systems, as well as operating procedures and regulations. This includes knowing how to operate the flight-management system efficiently and cross-checking entries against your clearance and charted advice.

These recommendations boil down to using good crew resource management. No matter what kind of operation you’re conducting—airline, charter, fractional, cargo, military, medevac, or personal—and no matter their title, give your co-pilots respect and recognize that they are a vital part of your team. AOPA

David Thornton is an airline transport pilot with 28 years of flying. He is currently a captain for a major bank flight department.