'Freedom to Fly': Witness to history

Eighty years is a long time for any company to be in business, but for a member-service special-interest organization like AOPA, it’s not just rare, it’s unprecedented. So, when I first began assembling the background material for AOPA’s eightieth anniversary history book, I was rather surprised to learn that in 1939 and 1940, AOPA’s tiny group of founders (and two employees) were not at all certain of success. There were competing general aviation organizations.

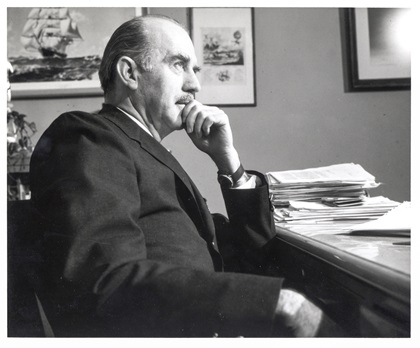

Thirty short years ago, I was “Doc” Hartranft’s guest on his ocean-going tugboat in Annapolis, Maryland. Our talk was wide-ranging. He spoke of AOPA’s formative months and his days as AOPA’s first employee, when attracting members was job one. If we didn’t sign up 2,000 members by the end of 1939, we’d lose our newsletter insert in what was to become Flying magazine—a critical element in broadcasting our goals, and adding more members. He spoke of sometimes tense relations with the Ziff-Davis group, then-publishers of Flying, political battles large and small, of AOPA’s wartime advocacy, the foibles of those he dealt with, and the crises of the 1950s, '60s, and '70s. “We never thought it [AOPA] would become this big and powerful,” he admitted. “We were too focused on day-to-day business to think about the future.”

At one point, he reached into his pocket and gave me a silver badge. It was a badge given to members who signed up for AOPA’s Emergency Pilots Registry during World War II. As far as he knew, it was the only one left.

In the months and years that followed, I began a hunt for historical documents that would provide background material for writing AOPA’s history. It was frustrating because of the lack of material. I can only surmise that every time AOPA moved its headquarters, or remodeled its offices, many documents, records, and artifacts simply went into the trash bin. I’ve seen it happen. One time we threw away an entire library. All in the name of reducing what was thought of as clutter.

The biggest and best trove of remaining letters, documents, photos, newsletters, and magazines were tossed in a large vertical filing cabinet in a downstairs office. Its shelves had collapsed under the weight, and all those papers and photos were in a two-foot-high pile at the bottom. In that collection you could see how the way we’ve communicated has changed. First, carbon-copies on onion-skin paper, and telegrams for urgent messages. Grease pencil for making crop marks on black-and-white photos. As the staff grew, the 1960s and '70s brought reams of internal memos, bearing the “write it, don’t speak it” slogan across the top. That, and more, formed the bulk of the source material for writing about AOPA’s first 25 to 30 years.

Then, by the 1980s, no more memos or telegrams. Was this a result of telephone calls and email—no longer an expensive luxury—becoming the norm? There are seldom any records of these kinds of communications. So, the sources then became newspaper and magazine accounts of events—and then, database searches as computers went mainstream in the 1990s. The bulk of AOPA’s archives was given over to the Hagley Museum of Wilmington, Delaware, for safekeeping, and it’s there that we copied and collected the materials from 1939 through the early 1970s. On one trip to Hagley, I opened an unnamed envelope. In it was the same silver Emergency Pilot’s Registry badge that Doc gave me in 1988.

We also drew on AOPA’s and AOPA Pilot magazine’s own remaining photos and other archival material (used in support of current magazine production)—which is stored in a warehouse near headquarters.

It’s remarkable what we’ve been able to amass for Freedom to Fly, despite all the challenges. It’s all together in this one book, which is not just a history of AOPA. It’s a history of GA in the United States, and I believe it may be the only such work of its kind.

This hardbound 288-page labor of love came together over the past eight months and involved virtually the entire publications staff of AOPA Pilot and AOPA Flight Training magazines. We put together the best of the source material available—and then some—along with sidebars on GA's cultural, manufacturing, military, and political contributions over the years. If anything, it’s proof that GA wouldn’t be what it is today without AOPA’s efforts.

Preorder your copy of Freedom to Fly by Dec. 5 for free shipping by the holidays.