Although thunderstorms are mostly a warm-weather phenomenon, one of their main dangers is ice. Warm air rising in thunderstorms will cool, eventually enough to begin forming ice crystals that grow until they are heavy enough to begin falling as hail.

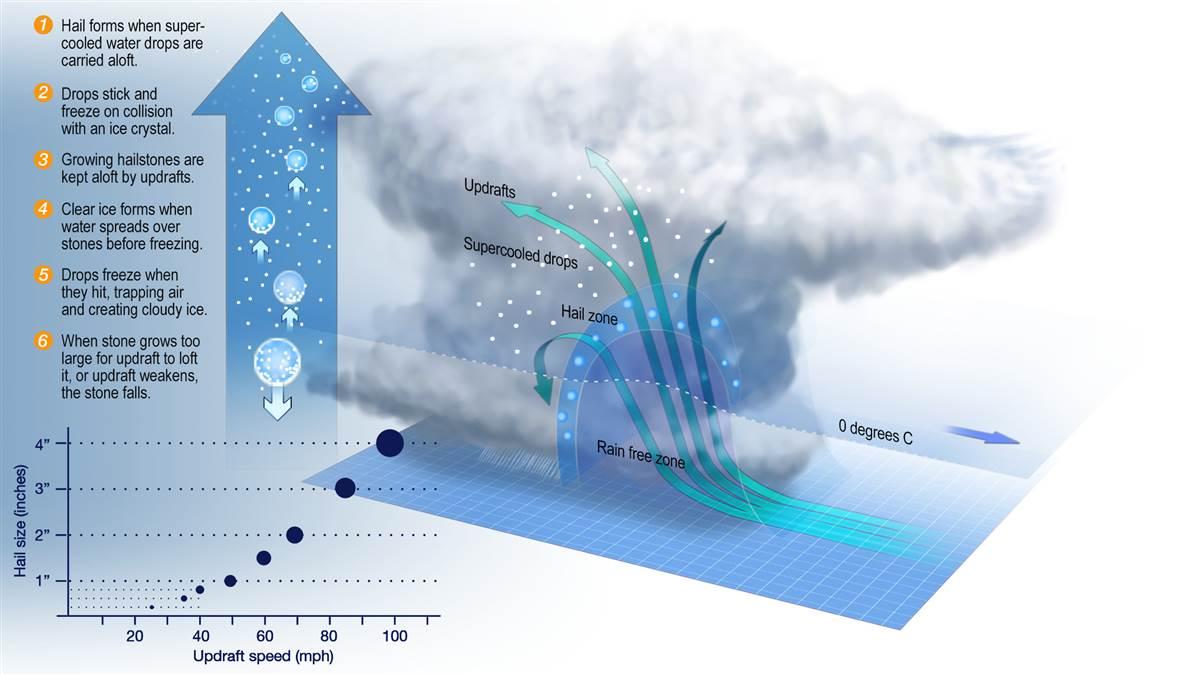

Hailstones are a sign of an even greater danger of thunderstorms: strong up- and downdraft winds that create extremely violent turbulence. The size of hailstones depends on the speed of the thunderstorm updrafts: A 24-mph updraft will form stones about a quarter of an inch in diameter, while a 98-mph updraft will form hailstones 4 inches across.

As a general rule, the speeds of thunderstorm downdrafts are roughly half the speed of its updrafts. A thunderstorm producing three-quarter inch hail has 40-mph updrafts and 20-mph downdrafts. If you fly into the storm you could run into a 20-mph downdraft and then immediately into a 40-mph updraft, or the other way around. Such differences in the velocity of airstreams close to each other would create a bump you won’t forget. In other words, hail falling from a thunderstorm is a sure sign of strong turbulence in the storm; the larger the hail, the worse the turbulence.

Although large hailstones are one measure of the violence occurring inside a thunderstorm, the apparent lack of hail doesn’t mean a thunderstorm couldn’t shake the fillings out of your teeth. Meteorologists estimate that 10 percent of all thunderstorms produce hail. As a thunderstorm moves through the sky, hail will be falling from a small part of it, creating a swath about 10 miles long and a mile or two wide. Some hailstorms have left a 100-mile path up to 10 miles wide. Hail is also a danger to airplanes on the ground. On April 28, 1995, hail hitting Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport caused $640 million in damage, mostly to parked airplanes.