Full circle

Around the patch and back in time

So it was with me and an Aeronca 7AC Champion, N81881 (eights over aces, if you play poker). I had my aerial baptism in this rag-covered taildragger at Bell Air Service on Clover Field (the now-embattled Santa Monica Airport) in Southern California when I was 14 years old. It was the trainer in which I soloed on my sixteenth birthday and in which I mercifully passed my private pilot checkride on my seventeenth. It was in 881 that I became a commercial pilot and a flight instructor when I was 18. It also was the airplane in which I taught my earliest students to fly. The little Champ and I share a great deal of history.

N81881 sold new in 1946 for $2,295 (sans electrical system). When I first crawled into its front seat on November 7, 1952, the Champ rented for $7 per hour (wet) plus four bucks for the instructor. It seems as though everything else in those days cost about a quarter—an aeronautical chart, a gallon of 80-octane avgas, a pack of cigarettes, a movie ticket. This was not as cheap as it sounds. My after-school job at the airport paid the minimum hourly wage of 75 cents, meaning I had to slave 15 hours polishing a bare-metal Twin Beech with Nevr-Dull in exchange for an hour in the air, but it was worth it. There were no Hobbs meters; we paid on the basis of a recording tach that gave us a little extra flight time.

Learning to fly was simpler then. You concentrated on the nuances involved in maneuvering the craft without the distractions caused by glass panels, high-tech avionics, and an overload of flight data. You laid out your cross-country route with a yardstick and flew almost anywhere without worrying much about airspace restrictions. Navigation by dead reckoning and pilotage was fun and reliable. Sure, we got lost once in a while, but this added to the challenge and made us better pilots. The private pilot written exam was a mere formality consisting of 50 common-sense, true/false questions taken from a booklet of 200 questions distributed to student pilots.

Approaching my eightieth birthday earlier this year—I thought it would take a lot longer to get this old—I realized that I had been flying for 66 years. I wondered if the old trainer that had taught me so much about flying had survived the ravages of time, or if its N number had been passed unceremoniously to another aircraft. A check of FAA records revealed that the little Champ was alive and well and living in Livermore, California (east of San Francisco). I contacted its owner, Jim Bottorff, a retired architect, who has owned the airplane for 30-odd years. I asked if he would allow me to re-create my first solo flight on my eightieth birthday in what has been the most meaningful and memorable aircraft of my career. He not only agreed but seemed to share in my excitement.

Bottorff later told me that Sam Rivinius, owner of Attitude Aviation, had graciously volunteered use of his large hangar to host a gathering of two dozen friends planning to join me in Livermore for a slice of birthday cake. Attitude is the largest flight school at Livermore Municipal Airport (LVK) and has a unique and wide variety of aircraft available for both dual and solo rental. These include a Piper Aztec, a Pitts S–2C, an Extra 300L, and a Piper Saratoga. Sadly, Rivinius doesn’t offer training in Aeronca Champs.

According to urban legend, N81881 once had been owned and kept at Livermore by Doren Bean, a pilot who had a fatal accident while flying a Pitts S–1. During the investigation, the FAA said that Bean did not have a pilot certificate but did have aliases. One of these was D.B. Cooper. In addition, Bean had bragged to locals about his parachuting prowess. This led some to believe that the Champ had once been owned by the skyjacker who, in 1971, bailed out of a Northwest Orient Airlines Boeing 727 with a $200,000 ransom.

I confess to approaching the little Champ with some trepidation. It was as though I were about to see my first love after a long absence and feared I would discover that the relationship was not as wondrous as memories had made it seem. No chance. My reintroduction to the Champ made me feel as though I had come home. The little airplane is gorgeous and has survived the decades much better than I have, the result of numerous restorations, paint jobs, and engine overhauls.

Bottorff spun the wooden propeller by hand, and the 65-horsepower Continental putt-putted to life. Visceral sensations emerged that were both familiar and comfortable. They helped me to quickly connect to memories of a past era.

Cleared for takeoff, I advanced the throttle and recalled a lifetime ago when a younger, stronger, and more nervous left hand had pushed forward on that very knob. I had no concept at that time that a teenage desire to fly would be the dawn of a fulfilling career packed with passion, excitement, and adventure. In fact, I almost quit flying after my first hour. Fuel leaking from the gauge and into the cabin had made me airsick. The leak was thankfully repaired before my next flight.

After liftoff, I chuckled at the memory that you spend most of your time in a Champ climbing. On a warm day at sea level you’re lucky to get 300 fpm.

Aeronca owners acknowledge that cross-country flying is slow but possible. You can keep up with freeway traffic but only when traffic is slow. If you lose patience while flying into a headwind and getting nowhere fast, you can turn around and head the other way. After all, where a Champ pilot flies is not as important as the joy he has in getting there. Champ pilots also become topographical experts. The terrain beneath our wings moves so slowly that there is time to enjoy and study what others see only as a blur.

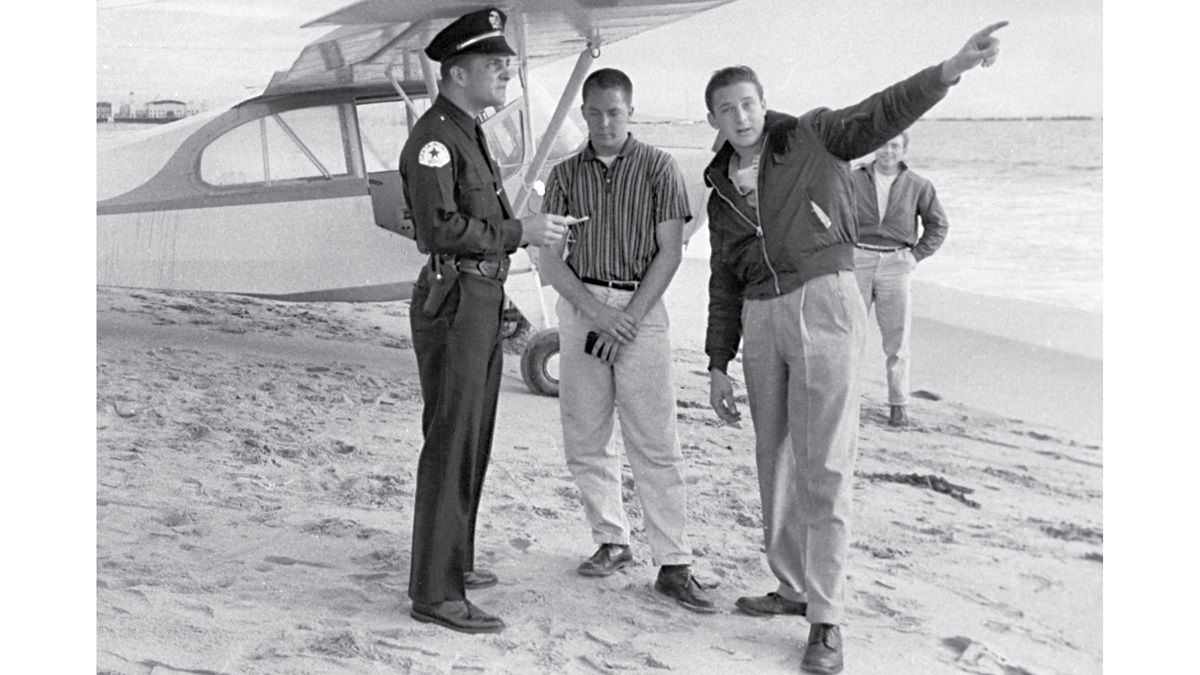

One of my most memorable flights in this Champ occurred when I was 18 and giving presolo instruction to Griff Hoerner. For reasons I’d rather not discuss here, we wound up suffering total power loss and gliding toward Santa Monica Beach. Fortunately the tide was low, and we landed easily on the exposed band of hard-packed sand. A police officer soon arrived on the scene and seemed to take sadistic delight in issuing a violation for the “illegal parking of a motor vehicle on a public beach.” The judge was more understanding and threw out the ticket.

At the risk of being accused of heresy, I am compelled to declare publicly and irrevocably that the Champ is a better airplane than its rival, the Piper J–3 Cub. Both have the same engine and similar performance, but the “Airknocker” is roomier, and you solo it from the front seat. Cub pilots must solo from the rear, which leaves much to be desired. What I do like better about a Cub is that it can be flown with an open door, a delightful advantage on a warm summer afternoon.

When I brought the Champ to a halt at the end of my commemorative solo flight around the traffic pattern, I turned off the mags, sighed, and watched the wooden propeller tick to a stop. I closed my eyes momentarily and remembered fondly some of the students we had taught to fly. I recalled with gratitude many of the mistakes this little airplane had allowed me to survive and the ham-fisted blundering it had forgiven. N81881 protected me from myself during the formative years of my career. No other airplane ever taught me as much or as well. No other airplane ever will.

If you’re tall, getting in and out of a Champ requires the flexibility of a contortionist, and it didn’t help that I had picked up some girth since the last time I had flown a Champ. After watching me struggle to exit the little trainer, Mike Wedemeyer, a high-school classmate who had driven to Livermore from his home in Roseville, California, noted tactfully that the “cockpit of this airplane seems to have shrunk a bit.”

As I walked toward the hangar to join my friends for lunch, my wife, Dorie, and two others wearing devilish grins and carrying a large pair of scissors strode purposefully toward me. How, I wondered, would I save the shirttails of my new Tommy Bahama shirt from this time-honored ritual? Thankfully, Rivinius saved the day by calling me aside in the nick of time to meet John Marchand. The mayor of Livermore had come to the airport to present me with a proclamation from the city council taking special notice of this joyful day.

I could not accept such an honor from His Honor without feeling obligated to mention at least a few municipal highlights: Livermore Municipal Airport is home to 600 based aircraft; the city boasts the world’s longest-lasting light bulb, which has burned continuously in the fire station since 1901; Livermore is home of the famed Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory after which the 116th element on the periodic table, livermorium, was named.

A reward of learning to fly is the privilege of carrying passengers. I remember my first as clearly as yesterday—Diane Phillips, my high-school sweetheart. She now lives in Minden, Nevada, and eagerly drove across the Sierra Nevada to celebrate and re-create our first flight together.

As I buckled Diane into the rear seat of 881, sweet memories of an innocent and adolescent romance began to emerge from behind the foggy mists of time, even though a lifetime had passed between this encounter and our last. The yellowing, brittle pages of my first logbook, a skinny little thing barely held together by ancient threads, reveal that we made 14 flights together during our senior year in high school. I had never wanted any of them to end.

I didn’t know what Diane was thinking as we lifted off and began climbing toward a rendezvous with the past, but I was consumed with thoughts of our previous flights together. Unfortunately, the passenger in a Champ sits in the back. Without an intercom, speaking with one another is almost impossible, so whatever thoughts we had at the time had to be kept to ourselves. Diane told me later that she had spent our time aloft “restoring forgotten memories.”

Thomas Wolfe wrote that “you can’t go home again,” but the reality is that you never leave. Nostalgia, a consequence of getting older, can also provide great comfort.

Flying in command on my eightieth birthday, June 23, 2018, qualified me for membership in the UFOs, the United Flying Octogenarians. On that day I became the youngest member, a claim that sadly won’t—or didn’t—last very long.

My good friends Doug and Sue Ritter, who also celebrated my sixtieth and seventieth birthdays with me, were at my eightieth because they wanted “to see an antique fly an antique.” They say that they will be there when I do it again in 10 and then 20 years. Ha! The Champ and I should live so long. On the other hand, we’re both as young now as we’ll ever be, so there’s no reason not to plan future flights together.

These commemorative eightieth birthday flights in N81881 have taken me full circle, but they were not the lyrics of my swan song. Even though I have already had complete and gratifying careers as a pilot and an aviation writer, there remain so many more different types of airplanes I yearn to fly and so many more wonderful people I hope to meet. Whatever follows, though, will be icing on the cake (preferably chocolate).

Web: barryschiff.com

Photography by Mike Fizer