Never Again: A new low

Tempted to test limits

By Steven Davies

I have always been a conscientious pilot who goes to safety seminars and uses personal minimums. I could never imagine putting myself in the kinds of situations I read in “Never Again,” but there I was.

I was flying in the right seat of a Cessna 177RG out of Spanish Fork Airport Springville-Woodhouse Field (U77 at the time, now SPK) in Utah. The more experienced pilot was pilot in command.

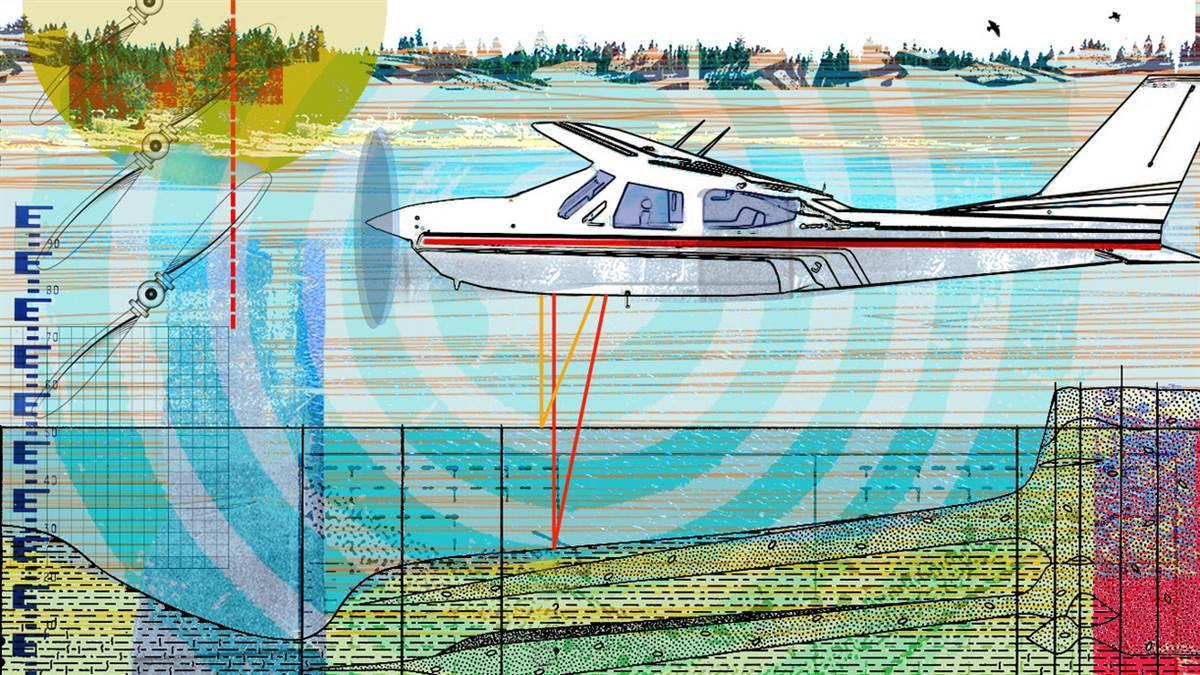

This Cardinal had a laser altimeter, adapted from large unmanned aircraft systems, installed under a supplemental type certificate. It gave height above terrain readouts and callouts like the radio altimeter systems in turbine and jet aircraft. One of the manufacturer’s caveats was it would not operate over water.

We enjoyed a relaxed sightseeing flight over the canyons east of Springville. On returning to the area we tuned to the common traffic advisory frequency only to hear a recorded message that the airport was closed. We’d read a notam saying they would be working on a runway extension but hadn’t paid attention to the time of the closure. No problem. Provo Municipal Airport (PVU) was only 5 nautical miles northwest. We decided to land there and have an early dinner at the airport restaurant. By then, Springville would be open.

We were cleared to land on Runway 13 at Provo. The downwind, base, and final legs to Runway 13 are over Utah Lake. As we descended on base leg, the laser altimeter started making altitude callouts. It was totally unexpected since we were over water.

Over dinner we devised a plan to determine if the laser altimeter did indeed work over water. We wanted to determine at what height the laser altimeter would provide readings, and whether it was reporting height above the surface or height above the bottom of the lake.

The south end of Utah Lake is a narrow strip bordered by marsh on the northwest and dry lake bed on the southeast. We would fly over that strip of lake, landing gear retracted, from northwest to southeast at an airspeed and altitude that would allow us to make a forced landing on the dry lake bed if we had any problems.

The next morning, we made four uneventful passes over the lake. I monitored the laser altimeter and made altitude callouts to the PIC. The first pass was at 800 feet descending to 600 feet with no altitude readout over water; second was at 400 feet descending to 250 feet with no altitude readout over water; third was at about 100 feet with good altitude readouts; fourth was at about 50 feet with good altitude readouts. I said I wanted one more pass and thought I indicated to test between 250 feet—where we had no altitude readouts—and 100 feet—where we had good altitude readouts.

During the fifth pass, I was alarmed at how low we were. I quit making altitude callouts and looked up to see why we were flying so low. The PIC, perhaps believing we were in level flight, continued descending until the bottom of the cowling struck the water. The water forced the nose up. Fortunately, the sudden increase in pitch was enough to compensate for the reduction in airspeed from the water drag and the aircraft climbed out of the water.

Our temporary relief turned to fear. The engine rpm was high, and the propeller pitch control didn’t have any effect. We were 10 nm southwest of the closest airport—U77. We quickly decided to return. We called on the Springville CTAF that we wanted a nonstandard right base approach to Runway 12.

As we approached the airport we saw trucks and personnel working off the approach end of Runway 12. On short final, we lowered the landing gear and lost altitude as the landing gear deployed. We were low enough I could almost see the expression on the ground personnel’s faces as they scattered. It looked like we might clear the trucks but shear off the landing gear on the exposed end of the runway concrete under construction. We cleared the trucks and by some miracle the main gear touched down on the runway.

The seriousness of the situation became more apparent when we taxied back to the hangar. Even at a high engine rpm, the aircraft could barely taxi. We would later learn the propeller governor was damaged, both propeller tips were rolled back from striking the water, and one of the blades was at risk of coming off. In hindsight, a gear-up landing on the dry lake bed would have been more expensive but more prudent.

A very upset airport manager arrived at the hangar just after we shut down the engine. I imagine he was about to dress us down, but he stopped when he saw the condition of the aircraft.

The question I have asked myself many times is: How could two conscientious pilots put themselves in this situation?

I use the PAVE and IMSAFE checklists when preparing for a flight. All looked good. I know the FAA hazardous attitudes and avoid them. I have come to the conclusion we were doing a flight maneuver we were not trained for, had not accounted for all the risks, and had not sufficiently established the division of responsibilities and communication between the PIC and me. Every seaplane pilot will tell you judging height over water can be difficult, particularly when the water is calm. We were two pilots with no seaplane experience flying extremely low over calm water. We should have established a floor; I should have spoken up when I was uncomfortable with how low we were.

I have a new rule. I ask myself: Am I operating an aircraft outside performance limitations in the pilot’s operating handbook? Am I performing maneuvers I have not been trained to do? Am calibrating an instrument using unpublished procedures? Am I operating an aircraft less than 500 feet above water for a maneuver other than a normal takeoff or landing?If the answer is yes to any of these questions, I am a test pilot. I am not qualified to be a test pilot, so, I should not be doing any of those things.

On the up side, reviewing the altitude reported by the laser altimeter when the aircraft struck the water, we concluded the laser altimeter was reporting height above the surface of the water. I guess you could say our foray into being test pilots was successful, but could have come at a cost I have no interest in paying.AOPA

Steven Davies is a private pilot who lives in Ontario, Canada.