Drone, drone on the range

Researchers spot feverish cattle from above

Researchers flying drones at Texas A&M University may soon determine just how much standoff distance is required to avoid spooking a cow. This is one critical step toward a larger goal of more precisely targeting antibiotic administration and improving the life of livestock with flying robots.

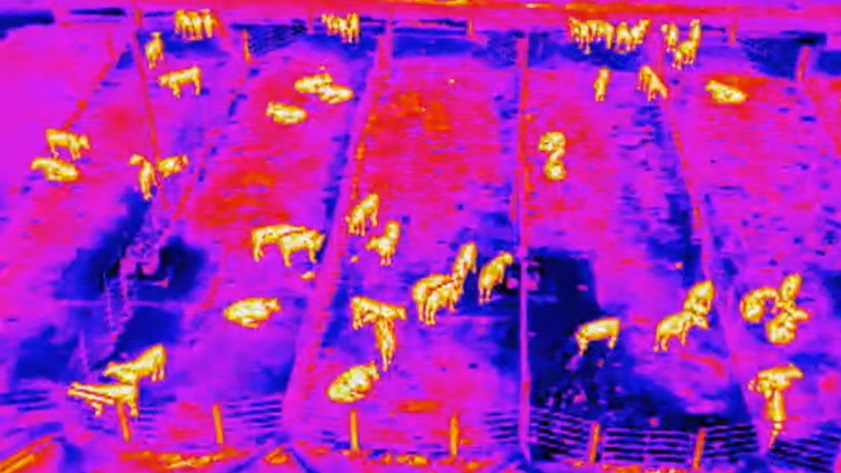

At a research feedlot just west of the Texas Panhandle city of Amarillo, researchers are in the early stages of exploring how heat signatures from cattle might correlate with other data to speed detection of stress or disease. The idea stemmed from thermography used in veterinary practices diagnosing lameness in horses. Ultimately, Texas A&M researchers hope to develop test methods to identify feverish animals before they show symptoms of illness or infect other animals. More precise targeting of antibiotics would reduce overuse of drugs, which leads to the rise of drug-resistant strains in livestock as well as humans as the microorganisms adapt.

Auvermann and his staff were trained by an Amarillo flight school two years ago, and recently renewed their certifications. “Now that Part 107 rules are in place, that really threw the field wide open. We didn't have to hire specialized pilots to do it for us. We could get trained ourselves,” he said. Auvermann recently completed additional training to prepare for applying to the FAA for a daylight operations waiver. Thermal imaging can be more complicated during the day when a black, brown, or pale cow might reflect different amounts of heat. Nighttime becomes more of an equalizer.

Thermography has long been a tool of veterinary medicine, but aerial thermography is an entirely different proposition.

“It's one thing to have a horse isolated on the ground under control, perhaps even sedated in a large animal veterinary clinic and do some very close-up thermography,” Auvermann said. “It's another thing entirely to try to do it from the air, from a mobile platform on mobile animals, without them knowing it's going on.”

The Amarillo location is one of 13 statewide in the Texas A&M University AgriLife fold. Drones are used at other locations, and dozens of certificated pilots are on staff. The College Station agency headquarters and the Corpus Christi center lead the way in drone use within the university system. In Corpus Christi, crops including cotton and sorghum are monitored by drones for signs of stress, including disease. The imaging from drones can help measure the size of the bolls on cotton, and through multi-angle imaging, the number of berries on a sorghum head. Drones already have a proven track record in “precision agriculture”—a term for technology-assisted farming that includes using drones to analyze soil conditions to guide irrigation and fertilizing efforts in addition to monitoring yield and stress.

Auvermann expects that drone imaging, paired with artificial intelligence and more traditional observations, will evolve quickly, given how frequently the technology has advanced. Prior to enlisting drones for animal study, Auvermann said wheat breeding has been the primary focus of the unmanned aeronautical efforts in Amarillo, capturing images to monitor how different varieties of wheat react to stress.

The Texas A&M system takes flight safety very seriously. Auvermann said university pilots, in addition to following FAA regulations, follow additional rules and guidelines developed by the university. At the Amarillo campus, an air ambulance is based barely a mile away. That helicopter service is contacted before unmanned operations in the vicinity mutual awareness. The feed lot where the cattle are being studied is in Class G airspace, but Auvermann doesn’t let that breed complacency in crop-duster country.

“We don't cut corners. I won't allow it.” said Auvermann, who is keenly aware that great diagnostic advances using drones could quickly be overshadowed by an accident. “We go by the book.”

Auvermann has a small air force at his disposal, including DJI Matrice 100s, M600s and Phantom 4s. Their duties range from carrying the aforementioned imaging gear to producing marketing material. For thermal imaging, a Zenmuse XT 19mm infrared imaging system is hung on a Matrice 100. Thermal imagers can run from a few thousand dollars to those that quickly eclipse the cost of the most expensive drone. The Zenmuse is an uncooled microbolometer. Say what? If that begs breaking down, “uncooled” means the affordable end of the sensor scale versus a more sensitive, stable “cooled” sensor. A bolometer is essentially a thermometer that uses radiation to affect electrical current changes. These are the same type of sensors sometimes used in search and rescue missions and by fire departments to quickly analyze heat sources at a fire scene.

Auvermann and his staff need to learn how low and long they can fly over cattle and not disrupt their normal behavior. Since any artificial intelligence formulations are partly based on normal behavioral data, it’s important to not change what “normal” is to cattle. Simply put, don’t spook the cows.

Also to be determined is how best to mark or otherwise identify a feverish cow spotted from the air and direct care on the ground to the correct animal. Again, stressing the collaborative nature of various tools, Auvermann suggests that some sort of sensor or subcutaneous implant might be used to distinguish animals. If a feverish cow can be culled from the herd early with the assistance of aerial imaging, that might avoid the need to treat a larger group with antibiotics.

“Across the industry, cowboys and cowgirls on horseback, and veterinarians in pickup trucks, are laying eyes on every single animal every day to identify those showing signs of illness,” Auvermann said. “The question we're addressing with our nascent UAS, fixed-camera, and artificial-intelligence programs is: can we automate that function without sacrificing accuracy? We think that the sky is the limit, literally, in the utility of drone-based remote sensing.”