The 7 percent

When Abingdon Mullin was starting the Abingdon Watch Company, she met a man who said he would be happy to help fund her ambitious venture. But there was a catch. Mullin had to “make him feel like a kid again” while his wife wasn’t at home.

When Abingdon Mullin was starting the Abingdon Watch Company, she met a man who said he would be happy to help fund her ambitious venture. But there was a catch. Mullin had to “make him feel like a kid again” while his wife wasn’t at home.

At the time of the harassment, Mullin was a customer service representative at a prominent flight school at the Santa Monica airport and had just finished her private pilot certificate. The man who propositioned Mullin was a regular customer at the business, which also had an FBO. To help her feel safe at work after rejecting the advance, Mullin’s boss helped hide her every time the man came in. She said the corporate office didn’t seem concerned since the incident took place off the property.

Since then Mullin has gone on to a successful career ferrying airplanes and as an airline pilot, along with running the Abingdon Watch Company. However, she has been told her success is because she slept her way to jobs and other opportunities.

Mullin’s story isn’t unique. Women involved in aviation have countless stories of facing some form of harassment or discrimination during their training, at the airport, or as part of their career. Yet the women interviewed for this story said that although harassment can be part of the job, they don’t dwell on it.

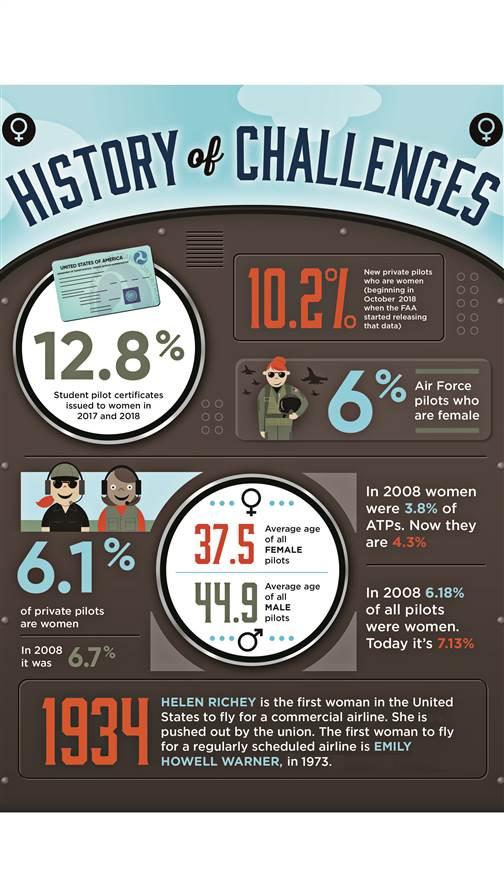

Female pilots make up about 7 percent of all certificated pilots. Just 10 years ago the number was closer to 6.2 percent. Professional pilot ranks are even less diverse, with women holding 4.3 percent of airline transport pilot certificates. Depending on how you look at it, these numbers are either a stark improvement after years of stagnation, or a dismal record that is being outstripped by dozens of industries that are historically male dominated.

Peggy Chabrian thinks we should be looking at the positives, including an increase in the number of female pilots. Chabrian is the president and founder of Women in Aviation International (WAI), one of a few groups that advocate for a greater representation of women throughout the industry, especially in professional settings. Chabrian said the fact that women have gone from around 1.9 percent of ATPs in 1990 to more than 4 percent is proof that the trend is at least headed in the right direction.

Peggy Chabrian thinks we should be looking at the positives, including an increase in the number of female pilots. Chabrian is the president and founder of Women in Aviation International (WAI), one of a few groups that advocate for a greater representation of women throughout the industry, especially in professional settings. Chabrian said the fact that women have gone from around 1.9 percent of ATPs in 1990 to more than 4 percent is proof that the trend is at least headed in the right direction.

Yet the gender barrier was broken at a U.S. airline in 1973 when Emily Howell Warner was hired at Frontier Airlines. That means it’s taken 46 years to get to a point where there are still fewer than 7,000 active female ATPs. Other statistics are even more troubling. The United States lags the world in female airline pilots as a percentage. Worldwide, women make up more than 5 percent of all airline pilots, and an Indian airline fills the cockpit with more than 13 percent women. Hawaiian Airlines leads airlines in the United States at just less than 10 percent. All this is according to data released by the International Society of Women Airline Pilots.

Similarly, in recent years, women made major gains in the labor market; the female pilot population remained virtually unchanged. It may be easy to say that these things take time, there are big cultural shifts that need to occur, and things will improve. Yet other industries saw massive increases in female employment. In the past 15 years, at least 20 industries have seen the percentage of women in the workforce increase by more than 6 percent, including careers as diverse as pharmacists, writers, bakers, public relations executives, and veterinarians. Veterinarians went from 34 percent female in 2000 to 59 percent female in 2016. The parallels are strong: Being a vet takes significant schooling and training, is a major investment, and has a long payoff.

In fact, even in many careers most would consider male dominated, women make up a larger percentage of the workforce than they do in professional piloting. Nearly 7 percent of truck drivers are women, 12.5 percent of police officers, 30 percent of farmers, and 9 percent of the construction industry.

Defining the problem is easy. Figuring out why aviation continues to be this way and what must be done to change it is hard.

Stubborn problem

Ask any female pilot about the slights or harassment they’ve faced, and each one has a story. Sometimes it’s as harmless as being mistaken for a customer service representative or flight attendant. In other cases it’s aggressive or even criminal. Then there’s the inherent sexism. GA News published a positive story earlier this year about a young single mom who was enrolled at an aviation university and planned to become a professional pilot. The online comments centered on how her ex-husband must be footing the bill.

Ask any female pilot about the slights or harassment they’ve faced, and each one has a story. Sometimes it’s as harmless as being mistaken for a customer service representative or flight attendant. In other cases it’s aggressive or even criminal. Then there’s the inherent sexism. GA News published a positive story earlier this year about a young single mom who was enrolled at an aviation university and planned to become a professional pilot. The online comments centered on how her ex-husband must be footing the bill.

Despite the headwinds, the women interviewed for this story brought up harassment only when questioned. Most said it wasn’t a deterrent, but rather something to work through or simply ignore.

A lack of mentoring and positive role models came forward as a significantly bigger challenge. It’s easy for men to imagine themselves in the cockpit as they see male pilots in movies, at the airport, and on an airliner, but for women those sightings aren’t frequent. “Many men falsely assume women don’t want to do it. They mentor boys instead,” said airline pilot and CFI Sarina Houston. “Personally, I wouldn’t have gotten into flying had someone not stepped out and given me a free airplane ride.”

An AOPA staff member recounted how she has seen many times at EAA Young Eagles rallies where parents will push the boy to ride first, or make sure the boy sits up front and the girl sits in back. The impression is that the boy is there to learn while the girl is there to take an airplane ride and enjoy the view.

“Society dictates that story,” Mullin said. “They’ve created the story that either women don’t fly, can’t fly, don’t want to fly, do want kids and can’t fly, et cetera. The story is permutated by society for however many decades that airplanes have been around. It’s only until we get people outside the circle that people will change mindsets and think flying as a woman is an option.”

Even for dads who are engaged in aviation and think they are projecting positive aviation role models to all their children, challenges abound. Eric Crump is the head of Polk State College’s aviation program in Lakeland, Florida. Crump said he once asked his daughter as they were getting on an airline whether she would like to be a pilot someday. “No, that’s a boy job,” she told him. “Her mother and I are both pilots; she’s been exposed to aviation in every imaginable respect since birth. I couldn’t believe she still didn’t think aviation was open to her,” he said. “That made it real to me that we have work to do as an industry and as a community.”

Some pilots speculate that because aviation sometimes makes it difficult to have a career and a family that women are naturally not as drawn to it as men. “My wife made a choice to focus on our family as her primary driver,” Crump said. “But she is still incredibly active in aviation in other ways that fit her desired lifestyle. It’s not an either/or question.”

Houston said she’s able to make aviation work as a career in part because of a strong support network and because she waited to fly for the airlines until her kids got older. She was a full-time flight instructor prior to flying for the airlines. “My delayed entry to the airline industry was because I wanted to be home with my kids,” she said. “It would have been very difficult to have small children and fly for a career.”

In many ways that fact is changing, in part because the airlines are hiring so quickly. “People have been able to progress quickly, which has allowed them to have more control over their schedules,” said Sarah Rovner, an airline pilot and owner of an aircraft ferrying company. “You gain seniority and that’s been attractive to having a career and family” for women.

In many ways that fact is changing, in part because the airlines are hiring so quickly. “People have been able to progress quickly, which has allowed them to have more control over their schedules,” said Sarah Rovner, an airline pilot and owner of an aircraft ferrying company. “You gain seniority and that’s been attractive to having a career and family” for women.

On the recreational flying side, other factors are potentially at work, including less free time, lower amounts of discretionary income, and difficulties in flight training. Nationwide the unadjusted gender pay gap for women is roughly 20 percent, meaning women have significantly less discretionary money for flight training. They may also have less time, two of the major impediments to learning to fly. A survey by Britain’s Office of National Statistics found that women spend about two hours and 38 minutes a week on hobbies, compared to four hours and 39 minutes for men. The study speculated that despite a growing equality at home, women continue to spend more time on family and chores than men, and that when not in leisure, “women were more likely to be performing unpaid work.”

Getting out of the aviation bubble is critical to attracting more pilots, and a more diverse group of pilots. Technology can help. “I think we’re seeing a small uptick in females because of social media,” Houston said. “Because we don’t have mentors from the top we’re mentoring each other from social media and email.”

Fixing gender bias and other failures in flight training may also help diversify the pilot population, said Mullin. “I remember sitting behind the owner of a flight school at a conference and he just started going off about how he doesn’t know how to talk to women, why they keep leaving the school, how to make them stay. When you think that women students are an obstacle, they will be an obstacle.”

There seems to be no agreement on how best to ensure women complete training at the same rate as men (more than 12 percent of students are women, but only about 10 percent of new pilots), but acknowledging there is a problem could be the first step. There is a disagreement in current educational research as to whether boys and girls learn differently or whether we set up the environment differently, and thus affect the outcome. One thing is clear: The antiquated idea that women simply can’t understand technical matters as well as men has long since been disproven.

Many organizations, such as Women in Aviation, are doing their part to provide mentoring paths for women. The group holds a Girls in Aviation Day every year that brings girls to the airport to expose them to aviation. When the effort began just a few years ago 3,000 kids and 40 chapters participated. Last year 15,000 young people were exposed to aviation through 100 chapters worldwide. “It takes a myriad of approaches and keeping it in front of people,” Chabrian said. “Mentoring is key to helping people, particularly if they are new to aviation.”

WAI also helps to administer scholarship funds that are open to both men and women, a point of debate within the community. The program started in 1996 with two $500 awards. This year WAI passed the $12 million mark. In 2019, the organization was planning to award 130 scholarships valued at $780,000.

It’s clear, however, that solving the problem will take more than money. Sometimes all that’s needed is an invitation, a bit of support, and an acknowledgement that for aviation to thrive, all are encouraged to join.

Email [email protected]

Better together

Many groups have formed to support female pilots

Dozens of organizations, both formal and informal, have formed to bring female pilots together to provide support, mentorship, and scholarships.

- Women in Aviation International. Probably the largest and best-known of the groups, Women in Aviation International provides scholarships, organizes Girls in Aviation Day, convenes a yearly conference, and has more than a hundred local chapters for support, camaraderie, and networking. Almost 50 are on college campuses.

Web: www.wai.org - The Ninety-Nines. The biggest women pioneers in aviation started The Ninety-Nines in 1929, and the group remains very active today. Also known as the International Organization of Women Pilots, the Ninety-Nines have more than 150 chapters all over the world for support, networking, and service.

Web: www.ninety-nines.org - The Whirly Girls International. Founded in 1955 to support women helicopter pilots, today Whirly Girls has more than 2,000 members around the world. The organization gives out hundreds of thousands of dollars in scholarships and supports active helicopter pilots through networking and mentorship.

Web: www.whirlygirls.org - Sisters of the Skies. An organization of minority women, Sisters of the Skies promotes aviation participation through community activities, social media support, scholarships, and more. Check the group’s website for ways to help support the next generation of minority female aviators.

Web: www.sistersoftheskies.org - Ladies Love Taildraggers. One of the many social groups organized to support female pilots, Ladies Love Taildraggers is as founder Judy Birchler describes it, “A loosely bound group of dynamic women pilots drawn together by one shared love” (see “Pilots: Judy Birchler,” p. 128).

Web: www.ladieslovetaildraggers.com - F.A.S.T. The name says it all: Female Aviators Sticking Together is a community of women pilots with the simple goal of inspiring and unifying female pilots. The group holds one-day summits and provides scholarships, networking opportunities, and career advice.

Web: www.femaleaviators.org