How it works: The altimeter

How high in the sky are you?

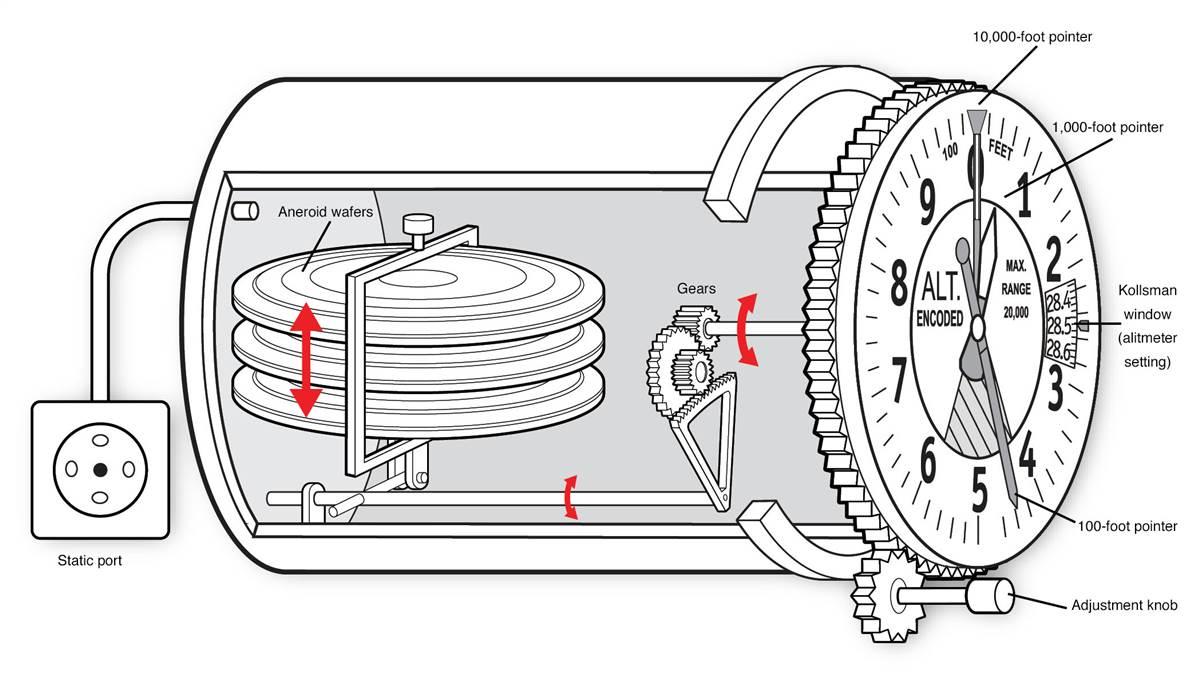

It looks like a clock, you read it like a clock, but it’s not a clock. The big hand is at hundreds of feet, the little hand is at thousands of feet. If there’s a small white line, it reads in tens of thousands of feet. What is this? It’s the altimeter, which proved its worth in aviation on the first “blind” instrument flight by James “Jimmy” Doolittle in 1929. (He would later lead the daring attack on Japan from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet after the United States entered World War II.)

The sensitive altimeter still used in aviation was patented in 1936 by Paul Kollsman, its inventor. The measurement of altitude is altimetry (bonus question: What is the measure of water depth? Bathymetry). The altimeter measures the height of an aircraft above a fixed level. The instrument senses this by taking the ambient air pressure from the static port. That air is plumbed through the back of the panel and into the back case of the altimeter. Inside the altimeter is a sealed disc called an aneroid, or bellows. As the aircraft goes up, the pressure inside the case decreases and the bellows expand. The opposite happens as the aircraft descends. The bellows are mechanically connected to the face of the instrument through gears. It is Kollsman’s invention that assists the pilot: The window on the front of the instrument allows the pilot to set the altimeter to the current local pressure, so it will display an accurate height above sea level.