On Instruments: Circling challenges

Maneuvering in sketchy circumstances

The patterns used in circling are up to you, but for single-runway circling, making an overhead entry that splits the runway (left) is popular, as is making a modified downwind entry (right).

Illustration by Kevin Hand

Circling approaches are sometimes offered as a sole means of getting into airports not served by straight-in landing minimums. You can quickly identify this kind of approach by looking at the approach plate header. If the approach plate identification header ends with a letter—such as “VOR-A” (or “B” or “C” if more than one is offered)—then that’s your tipoff that you’ll be landing out of a circle-to-land maneuver. Circling minimums are also published as options at airports offering traditional, straight-in procedures.

Circling-only approaches are established when the final approach course’s alignment with the runway centerline exceeds 30 degrees, and/or if the descent gradient is greater than 400 feet per nautical mile from the final approach fix (FAF) to the runway’s threshold crossing height (TCH). For a typical general aviation airplane approaching at 90 knots, 400 feet per nautical mile roughly equals a 600-fpm descent rate.

Circling can be a good thing. Let’s say that the surface wind direction doesn’t favor a straight-in landing, or that you see you’ll have low clouds obscuring your view of the runway threshold—but other runways are in the clear. Circling lets you fly to a runway with a nice headwind component, or to one more clearly in sight.

But this flexibility comes at a price. Circling minimum descent altitudes are higher than minimums for ILS, RNAV GPS, VOR, or other, more precise approach procedures, so if lower cloud bases are present, you won’t see well enough to safely land flying at circling minimums. Another issue arises while circling. You’ll only have obstacle clearance if you stay within the prescribed circling radius from the threshold of your runway of intended landing.

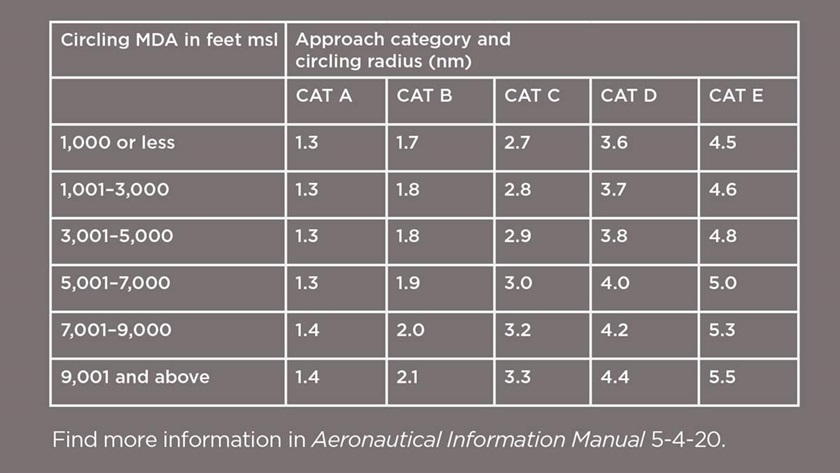

A typical light piston single, in its Category A approach category with a 90-knot maneuvering airspeed limit, is limited to a turning radius of a mere 1.3 nautical miles when circling at MDAs up to 7,000 feet msl. This could involve some steep bank angles, especially if your airspeed inches up, or the winds aloft are threatening to widen your ground track. Stall speed increases with bank angle, so steep banks are not a good idea when you’re flying this low to the ground (no greater than 30 degrees is a good rule of thumb).

Since 2012, expanded circling approach radii were introduced for some approaches. Expanded radii—identified by a black box with the “C” symbol within it—give you some extra room for swinging wide. But they mainly apply to higher approach categories, those used by larger, faster piston-powered airplanes, turboprops, or jets. Still, there’s no reason you can’t fly a circling approach using higher, Category B standards (a 1.7-nautical-mile radius for MDAs up to 1,000 feet msl) if you’re flying, say, a Cessna 172 and want more room to maneuver. Your minimums will go up, but you’ll have a little bit more time to get established on final.

Flying the approach

Let’s imagine you’re flying to an airport with a straight-in approach, but the surface winds are such that you’d be faced with a 20-knot tailwind when you land. You receive your approach clearance, tell ATC that you want to circle to another runway, and ATC approves. You leave the final approach fix, descend to circling minimums, break out of the soup before the missed approach point, and see the airport. You’ve already scoped out the approach plate’s planview for obstacles and other notes pertaining to circling, and know how and where you’ll circle. You level off, configure to land, and make your turn(s), being careful to keep the airport in sight and at the same time manage your bank.

If visual conditions exist, go ahead and land, making sure that you don’t leave the circling MDA until you’ve rolled onto your chosen runway’s extended centerline and are in a position to descend at a normal rate.

Curveballs

Now let’s say things go wrong while you’re circling. While you were concentrating on the turn to final in visual conditions, you inadvertently flew into a cloud layer moving over the airport. Suddenly it’s time for a missed approach. If you hadn’t already, you’ll have wished you’d briefed yourself earlier for the miss at this jarring moment.

The first order of business is to maintain control of the airplane. Then it’s time to get busy: inform ATC that you’re declaring a missed approach; turn to a heading that will take you over the runway threshold you planned on using to land; then turn to the runway the approach began with (which is usually where the full missed approach begins), climb to the circling MDA, and prepare to continue to the missed approach altitude. Here’s where situational awareness—and a good moving map display—will pay off.

ATC should issue instructions, which could be an initial vector or two—depending on your location, to give you separation from obstacles and any other air traffic—followed by a clearance to join a segment of the published missed approach procedure, or a combination of the two. This all assumes that you’re at a towered airport served by approach control, and covered by ATC radar.

But what if you’ve missed the approach at a remote, nontowered airport, and are too low for ATC to see or communicate with you? You’ll still have to do a missed approach, complete with turns and a climb over the airport, but without ATC’s oversight. Hopefully, your climb would put you at an altitude high enough to allow ATC to see and communicate with you. But what if there’s still no contact, and you’re still in cloud?

The only option left is to follow lost communications procedures, and to do that you will need to have route, altitude, and clearance limit information.

As for a route, flying the next route in your flight plan might be the best option, all the while continuing to try to reach ATC. This would be the route to your alternate, using the minimum altitudes for IFR operations. You did file for an alternate airport, right?

To minimize doubt when flying circling approaches in areas experiencing IMC and without complete ATC coverage, it’s best to get ATC’s advice on what sort of missed approach clearance, route, and altitude might be expected before beginning the approach. If ATC doesn’t offer it, you can ask.

Does thinking about any of this make you uncomfortable? Then only fly to circling-only airports when you know ceilings and visibilities will be high. Or do like the airlines, and just don’t fly circling approaches at all.

Email [email protected]

‘C’ for yourself

‘C’ for yourself