Maine: Happy trails

The Sugarloaf connection to miles of trails and unlimited outdoor fun

“Flying in the winter can be really, really amazing if you get the good weather,” says flight instructor Sawyer Fahy as he scans the mountains in the area where he grew up. Little Bigelow Mountain is barely visible a few miles to the north, although Fahy thinks the skies may clear soon.

Twenty-seven nautical miles to the southeast at Central Maine Airport of Norridgewock, Lincoln Benedict is checking the same view on the Sugarloaf webcam. He’s been consulting with Fahy by text message since well before sunrise. Howling winds overnight had become manageable by morning, so Benedict set out from Brunswick Executive Airport with his wife, Jessica Marion, with Norridgewock in mind as an alternate.

Benedict to Fahy: Couldn’t get a visual on airport when 8 miles out, diverting to Norridgewock. Snow squalls?

Fahy: Roger. Maybe we’ll keep an eye on it for a few and see if this snow shower moves out?

Benedict: Sure, will land in Norridgewock and see. Squalls to Rangeley from here but may clear.

Fahy: OK, that doesn’t sound too good.

Ski Mecca

With three rocking chairs facing the runway from between two vintage trainers, Fahy’s open-front hangar at Sugarloaf Regional Airport (B21) has the homey atmosphere of a front porch. Today, however, a mountain of plowed snow obscures the view. No one’s flying, anyway, as photographer Bob Knill and I fidget on the frigid ramp with Fahy and his wife, Stephanie, waiting for word from Benedict. We’re here to learn about the airport, and to tag along on a ski trek to Stratton Brook Hut, the newest of Maine Huts and Trails’ four ecolodges. If conditions are right, you can cross-country ski there from the airplane.

Carrabassett Valley has a population of about 500, but on winter weekends Maine State Route 27 is studded with headlights as skiers flock to the 4,237-foot summit of Sugarloaf Mountain Resort. And the area is becoming a year-round attraction, as bikers, hikers, and kayakers enjoy an outdoor center, extensive trails, and nearby lakes and lodges.

A trailhead connects the municipal airport to 82 miles of groomed trails maintained by Maine Huts and Trails, where cross-country skiers mix with snowshoers and fat-tire bikers in the winter, and hikers and bikers roam in the summer. The main corridor connects the nonprofit’s huts—a misnomer, as these off-grid lodges are modern facilities with vaulted ceilings, leather furniture, and commercial kitchens—as it weaves its way from Route 27 around the Bigelow range and Flagstaff Lake, up the Dead River to U.S. Route 201. When the first of the ecolodges opened in 2008, the trails were mainly used for skiing. Although skiing is still the most popular activity on the multi-use trails, paddling and especially mountain biking are growing in popularity.

This is Fahy’s home turf. He grew up in the area and learned to fly in the Pietenpol Air Camper his father built from plans after moving to the Maine ski town from the Bronx. After working for a seaplane operation at nearby Rangeley Lake, Fahy returned to the Carrabassett airport to open his flight instruction business, Sugarloaf Aviation.

Fahy suggests we duck into the field’s one heated hangar (others have been added since AOPA’s visit in March 2018), and as we walk he points out all the aircraft on the field owned by his students. “We’re running out of hangar lots since I started instructing,” Fahy says, smiling. He’s not joking: The town of Carrabassett Valley purchased an additional 2.5 acres to the north to develop for airport use. Fahy is hopeful that new hangar space will entice more airplane traffic to the valley, and that the new accommodations will include such luxuries as a bathroom.

The airport’s laid-back, open-air environment is pleasant in the summertime, when Fahy debriefs students at a picnic table. But in the winter, scheduling is less reliable—and post-flight debriefs are often spent hunched over the FAA Airplane Flying Handbook in an idling vehicle. A snow removal business keeps Fahy occupied on many of the days not suitable for flying.

Most of Fahy’s primary instruction is in the Cessna 172, but he makes sure every student gets at least some time in the Piper Super Cub. He doesn’t give instrument instruction. Sugarloaf only recently got an instrument approach, anyway—and its circling minimums are 2,900 feet msl. That’s more than 2,000 feet agl, if you’re counting.

“It can be a little bit unforgiving,” he says of flying in the valley, where the prevailing wind sweeps over the mountains from the west and then shifts down Runway 35. He teaches students to think of the air tumbling over mountain peaks as water in a rocky stream. “I think the students that I fly out of here have a respect for the conditions that not a lot of others do.”

Trailblazers

Marion knew after Benedict’s first ground school lesson that he was hooked. A senior videographer and art director for L.L. Bean, Benedict had started the lessons with the intent to parlay it into a drone operator’s certificate. But he had always wanted to learn to fly, and he had a mind for machines. He came back from a class talking about just one intro flight, but Marion knew better.

The energetic, 30-year-old Vermont native took to the new hobby with characteristic enthusiasm. He blazed through training in the Maine winter and bought a 1960 Cessna 172A he named Old Mustardsides for its vintage paint scheme. Soon, he and Marion were using the beloved airplane for regular day trips to destinations around the Northeast: a favorite ice cream stand, a biking trail, a ski resort. For their honeymoon in 2017, they took Old Mustardsides on a biking tour of Eastern Canada. With the backseats out, the 172’s 145-horsepower Continental O-300 carried the newlyweds, two road bikes, camping gear, food, and emergency supplies for the three-week expedition from Maine up to Newfoundland.

Old Mustardsides logged 120 hours in 2017, much of it on day-trip adventures of the couple’s own design. Active hikers, bikers, and skiers, they perused maps for airports that would connect them to activities they loved, and amassed a stable of favorite flying destinations (see “Favorite Haunts,” at left). Among them: Sugarloaf Regional Airport.

The only trouble is getting there.

An update from Benedict: They’ll wait another hour and reassess. The Fahys invite us to their home to warm up and pass the time. We drive past vacation rentals to the apartment the couple is renting, while he builds a house next door to his parents. Abundant outdoor activities and easy access to trails make this region an ideal place to raise their daughter, due in July 2018. It’s the right place for the Fahys, if not for everyone.

“A lot of people, living up here, they don’t understand it,” Stephanie says. “They’re like, ‘Where’s the nearest Target?’”

Cold comfort

The weather hasn’t improved, so Fahy leaves to pick up Benedict and Marion by car. By the time they return, it’s around noon. The sky has cleared, but the wind is howling down the trail at the airport trailhead. Given the late start and the headwind for the five-mile, uphill ski—and the fact that Knill and I are new to Nordic skiing—we leave backpacks with the gear shuttle, a snowmobile trailer, and start at a closer trailhead.

On the trail, I’m struck by the peace and calm of cross-country skiing. There’s no rush-and-stop pace like in alpine skiing, no dodging snowboarders—just the steady passage of pine and birch trees and the fresh mountain air. Our group stretches and contracts as we make way for oncoming skiers, an occasional snowshoer, and frolicking dogs.

The trail’s gentle slope is easy enough to manage, even for a beginner. But it steepens as we approach the 1,880-foot-elevation hut; Marion bounds up the hill effortlessly as I lurch and waddle behind her. When I realize I’ve dropped the nozzle to my Camelbak water pack, she and Benedict sprint downhill to retrieve it. I learn she recently competed in a 50-kilometer skate-ski race. Of course she did.

They rejoin us for the last stretch to Stratton Brook Hut. We drop off our skis outside the wooden lodge and follow a short path to an overlook, where we can see the 3,000- to 4,000-foot peaks of the Bigelow Range towering over miles of unspoiled forest. When we knock the snow off our boots at the entrance to the hut, the thermometer reads 9 degrees Fahrenheit.

We shed boots and layers in the mudroom and get a briefing near the entrance: the location of showers, times for dinner and breakfast, how to operate the composting toilets. Maine Huts and Trails’ sustainable lodges produce their own power through solar panels, super-efficient wood stoves, and, when necessary, back-up propane generators; we’re urged to conserve water and carry out our trash. Coffee and tea are included in our stay, but we can pay for extras such as local Roco Cocoa hot chocolate and Whoopie Pies in the Honesty Jar on the counter. Cups are in short supply, so we label ours and keep the same ones until morning.

Stratton Brook Hut is surprisingly cozy, heated mainly by radiant floor heat from a hyper-efficient wood furnace. With large windows and high ceilings, it has the ambiance of a luxury alpine lodge. We drop off our packs in the bunkhouse and settle in at a table, where Benedict offers us all canned herring and crispbread from his bag. When finished, Marion offers Benedict the herring juice from the bottom of the can. Fahy laughs, but Benedict drinks it. “There’s nothing Lincoln won’t eat—and happily,” says Marion. Fahy joins us for a family-style dinner before skiing back down in the dark, guided by a headlamp and the light of the moon.

Right seat

Although they’ve been to Stratton Brook Hut before, this is the first time Benedict and Marion have stayed the night. Their frequent flying adventures depend on a frugal mindset, and Benedict does everything he can to eke out more flying hours from Old Mustardsides. The extra time cleaning off frost is worth it for the three more hours a month he gains from choosing a tiedown instead of a hangar; he assists with the annual inspection to lower the price. And he buys mogas when he can, to keep the Continental engine happy—even carting back 5-gallon cans by car when they visit the couple’s favorite alpine ski spot.

Marion was uneasy with flying at first, but she understands what it means to Benedict. Goal-oriented and driven, she’s ill-suited to the passive role of passenger. She’s become an active participant, learning the ins and outs of ForeFlight and taking on other co-pilot duties—Benedict says Marion’s training in ornithology makes her especially adept at spotting traffic. She’s become interested in the parallels between aviation decision making and avalanche assessment and recognizes many of the same heuristic traps. When Benedict waffled over whether to fly to Sugarloaf this weekend, she challenged him: Would you make the flight if they weren’t waiting?

She’s been on one flight lesson, but she’s not interested in earning her certificate. “I don’t think I connect with machines the way he does,” she says. “I don’t think I can ever match that—the way he just loves the act of flying.” But flying takes them on adventures. When she’s aloft with Benedict, “It’s just amazing—to be up there and to see new views, and sometimes to go new places. That’s what I kind of love about it.”

Plane spotting

Sitting atop a giant snow mound near the runway, Marion squints at the horizon. There. She points to the two approaching airplanes in the distance. All I see are mountains.

Finally I see Fahy’s airplane as a speck in the saddle of two mountains. It’s several seconds more before I spot Benedict’s 172 behind him. Benedict skied down ahead of us this morning and got a ride from Fahy back to Norridgewock; he’s returning to pick up Marion and their gear. It’s still gusty as we watch as the two airplanes fly the pattern above us. Fahy looks a bit high on final approach, then drops suddenly in the sinking air before touching down. Benedict proceeds behind him, jostled about in the same bumpy air. He and Marion load the airplane, line up on Runway 35, and he briefs her on his plan. After takeoff he angles the airplane to the right and the mustard-yellow 172 shoots skyward in the orographic lift.

Later, Fahy checks in again by text message: Are you home?

Stopped at KAUG for a little ski!

Email [email protected]

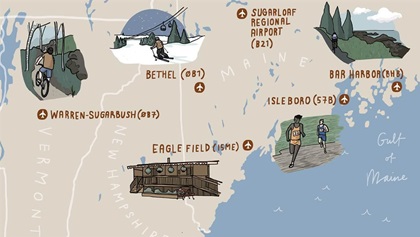

Favorite haunts

Favorite haunts