On Instruments: Going missed

Tense times at the missed approach point

Of course, there’s a corollary to that pronouncement: Sometimes it definitely isn’t. If your preflight briefing reveals that low clouds or visibilities, frontal weather, icing, or thunderstorms will be factors along your route of flight, then that’s when instrument flying comes into play. And if your destination’s forecast—from one hour before to one hour after your estimated time of arrival (ETA)—includes a ceiling below 2,000 feet above the airport elevation and/or a visibility below three statute miles, then an alternate airport must be named in your flight plan. This so-called 1-2-3 rule serves as a not-so-subtle reminder that there’s a chance your arrival may be complicated by having to perform a missed approach procedure.

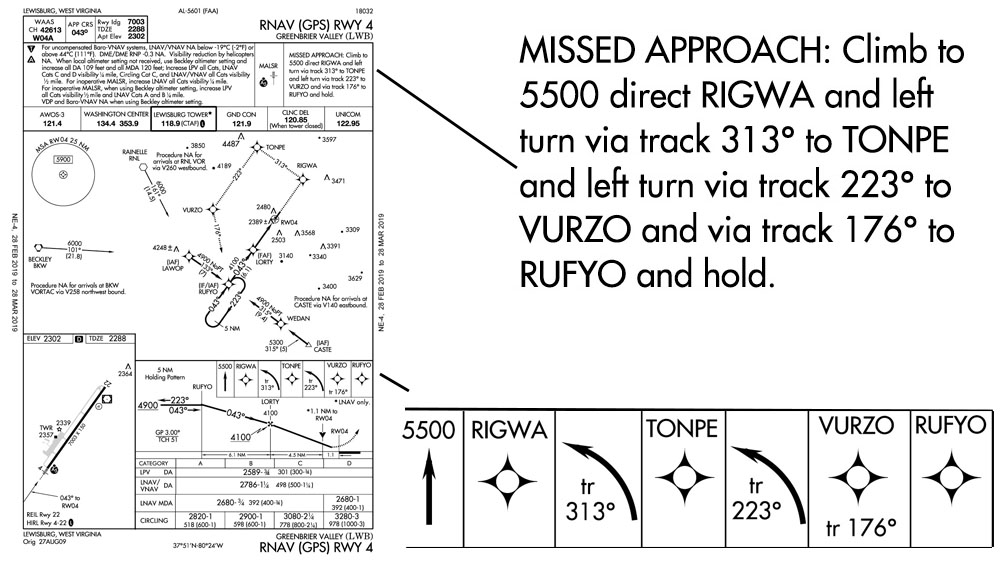

A missed approach is the IFR equivalent of a go-around in VFR operations. But it involves following a defined set of procedures should your visibility be compromised during the trip down the final approach course. In short, if you can’t see the runway environment when you reach the missed approach point as defined on an instrument approach plate, then you must climb away, following the published missed approach procedure.

In instrument approaches to airports served by approach lighting systems, you have a better chance of seeing the all-important runway environment. That’s because threshold lights, runway end identifier lights, touchdown zone lights, or runway lights can make the runway and its surroundings easier to see in low-visibility conditions. Even so, by the time you descend to the published decision height (DH—above ground level), decision altitude (DA—above mean sea level), or minimum descent altitude (MDA—also above mean sea level, published for nonprecision approaches), you have to be able to see the runway and descend to the touchdown zone at a normal rate of descent using normal maneuvers.

If the runway is served by the most sophisticated lighting, Approach Light System Sequenced Flashing arrays (the ALSF-1 and ALSF-2), then you are legally permitted to continue the approach and descend as low as 100 feet above the touchdown zone elevation as long as the red terminating bars or red side row bars are distinctly visible. This can be a big help when flying precision approaches—those with vertical guidance—to the common, typically ideal 200-and-a-half (200 feet agl, one-half statute mile visibility) approach minimums.

All these lights and markings may help guide you to the runway, but the regulations governing operations below DA, DH, or MDA (FAR 91.175(c)) lay down the law when it comes to descending below any minimum altitudes. Section (2) of that rule says that descents below minimum altitudes are prohibited unless the “flight visibility is not less than the visibility prescribed in the standard instrument approach being used.”

There’s that word again: flight visibility. This term carries an element of subjectivity in its definition, in that it’s “the average forward horizontal distance, from the cockpit of an airplane in flight, at which prominent unlighted objects may be seen by day and prominent lighted objects may be seen and identified by night,” according to the Aeronautical Information Manual. Strictly speaking, if the pilot reaches the missed approach point, can see the runway or one or more elements of an approach lighting system in use, then he or she can continue the approach to a landing—even if the latest local Automated Surface Observing System (ASOS), Automated Weather Observing System (AWOS), or Automatic Terminal Information System (ATIS) says the visibility is less than one-half mile. ASOS and AWOS stations analyze a small sample of the atmosphere near the airport’s surface, then use algorithms to determine visibility and other weather variables. They’re good, but they’re not a substitute for what the pilot can see when flying down final.

So flight visibility is the prime determinant. The nature of fog and cloud density is such that it can be so transparent or intermittent that it can allow pilots a view of the runway environment. (Note: We are talking about airplane operations under FAR Part 91 and to Category I ILS minimums in this discussion.)

Now let’s say the pilot is at the missed approach point’s DA/DH or MDA—or, even scarier, below those minimums—preparing to land, and the visibility turns so bad that he or she flies into fog or cloud and loses sight of the runway. A missed approach procedure must begin immediately. Same thing if the pilot can’t see an identifiable part of the airport while performing a circling maneuver at or above the MDA on a nonprecision approach.

Now’s when the stress level ratchets way up. Suddenly, there are a lot of steps to carry out, and quickly. You’re close to the ground, at a slow airspeed, and need to climb quickly. A massive configuration change is also in the offing, and you dare not sink while doing it.

First, in most cases, punch off the autopilot if you’ve been using one. Apply takeoff power and accelerate into a VX climb attitude. You had previously trimmed and configured the airplane for an approach, so all that power will radically change your pitch trim requirement as the nose pitches up. If you’re flying a retractable-gear airplane, as you see a positive rate of climb, gear retraction will probably be the next call (check the pilot’s operating handbook) in order to more quickly shed drag. Then, retract flaps in steps, as airspeed and altitude build. Accelerate to a VY pitch attitude and retrim as necessary. Get on the missed approach course, and stay there. Thankfully, many missed approach procedures have straight-ahead climbs in their initial segments, so this helps greatly. Make the radio call announcing that you’re executing a missed approach, but only after the trim is under control and you’re established in a climb.

Depending on your avionics, you may have to divert your attention from the gauges to activate the missed approach sequencing for guidance along the missed approach path. Some units require that you actually suspend sequencing to bring up missed approach guidance. Whatever avionics you have aboard, be sure you know it inside-out when it comes to missed approach procedures.

Does the first portion of the procedure seem overwhelming? If you’re not proficient it certainly can be, and many pilots have lost control in the few seconds or minutes after initiating a missed-approach climb. The abrupt pitch-up, as well as rapid trim and configuration changes, can induce spatial disorientation and vertigo.

What’s next? If you’re in a radar environment, ATC may ask if you want vectors for another try at the approach. But if the weather was so bad you already missed the approach, it will probably be just as bad the next time around. Pilots have run out of gas shooting approach after approach, so another one may not be the best move. Instead, flying to the published missed approach holding fix and entering the hold might be the way to go. Then you can sort out your options. ATC can help by informing you of the nearest airports having better weather and, of course, giving you another clearance.

Missed approaches often don’t get enough attention once a pilot earns an instrument rating. You can stay legally current by flying six approaches every six months, plus holding patterns and intercepting and tracking courses. The regs aren’t specific about missed approach procedures, but most diligent instructors will insist that they be demonstrated during instrument proficiency checks and other reviews. Even then, flying missed approaches under the hood, in good VFR, and near your home airport isn’t the same as taking on a complicated missed approach procedure in actual instrument conditions, at a distant, unfamiliar airport featuring high terrain and other curveballs.

This is where simulator training pays off in spades. You can fly the most taxing missed approaches in the craziest landscapes, over and over again, to proficiency—and without burning fuel or getting hurt. Your ego may get bruised, but that’s about it.

Email [email protected]