Purpose built

Dee Howard’s little-known gem

By Ken Scott

Durrell U. Howard—known all his life as “Dee”—never became a household name like William Boeing or Donald Douglas, but he was responsible for some of the best and most beautiful aircraft ever built in America. Although his formal education ended at age 15, his gifted mechanical mind took him from working on cars to airline mechanic to opening his own aircraft service shop in his home town of San Antonio, Texas. Eventually he would hold more than 30 patents, design and improve numerous airplanes, invent a practical thrust reverser, and convert a Boeing 747 for the king of Saudi Arabia.

In the 1950s, though, all that was in the future. Howard worked on whatever parked in front of his small shop, but he soon saw an opportunity to create aircraft for corporate executives who needed a fast, comfortable means of traveling to places that trains and airlines didn’t serve. There were thousands of World War II airframes (and even more engines) that might serve, but the transports—C–47s and C–46s—were too big and too slow while ex-bombers, such as the A–26, were plenty fast, but had limited room and were difficult to convert into comfortable traveling machines. All of them were noisy and none of them were pressurized.

Howard preferred Lockheeds. It made perfect sense. The PV–1 Ventura and PV–2 Harpoon were fast, roomy, tough, and had exceptional range—during the war the U.S. Navy used them to raid northern Japanese islands from bases in the Aleutian Islands. They were developed from prewar Lockheed aircraft initially designed to serve small airlines or big corporations—exactly the market Howard now had in mind. His decision to acquire and convert Lockheeds essentially completed the circle. Howard had a talent for finding talent—his early employees included Ed Swearingen, Bill Lear Jr., and Bulmaro “Cisco” Alarcon—and the skilled men and women he employed in San Antonio built dozens of modified Venturas.

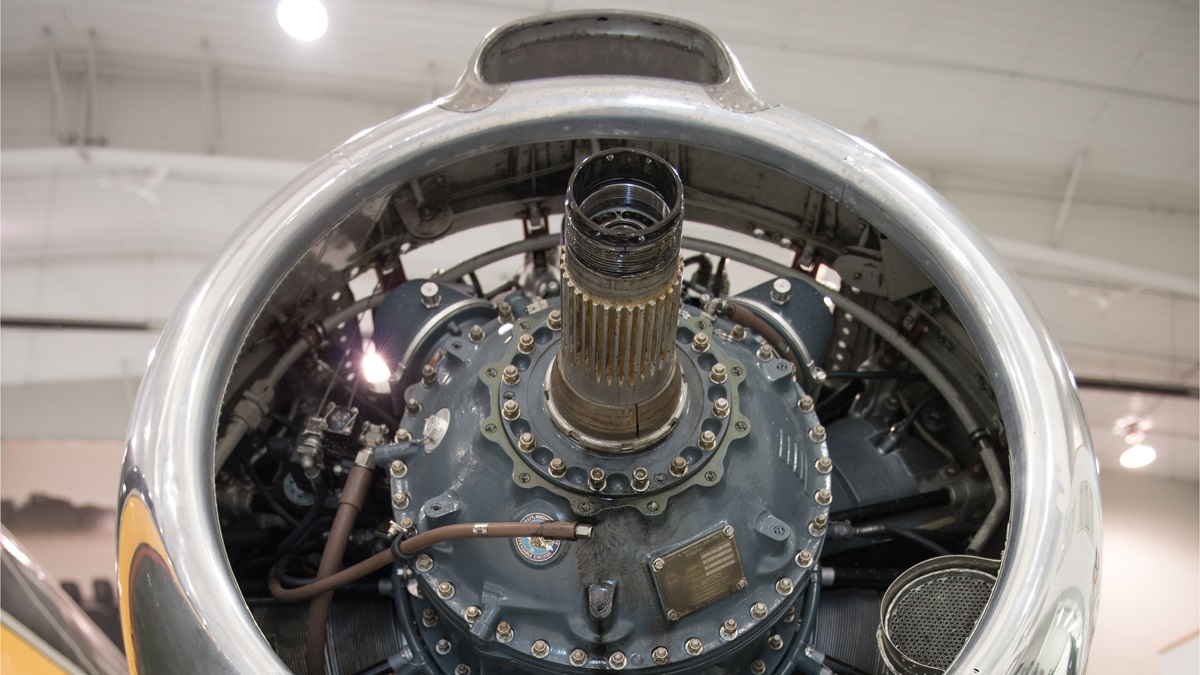

Finally, in 1958, their efforts culminated in the Howard 500. Despite its appearance, the 500 is not a converted Lockheed. Although it uses Lockheed outer wing panels and some other assemblies, it is an entirely different airplane, designed and built by Howard. The fuselage was built in San Antonio. Four feet longer than the Ventura, it was designed for pressurization—fuselage bulkheads are spaced every six inches. The cabin’s big enough for a small garden party or a big poker game. The low tailwheel allows entry though a vault-like door in the rear fuselage, with just a 12-inch step up—no ladders or awkward hatches. The deep belly held loads of baggage, and a loo in the back had running water. To move the airplane Howard chose DC–6 engines: Pratt and Whitney R-2800-CB16/17 radials capable of 2,500 horsepower. The result was an airplane that was smaller than the DC–3 but weighed more, had 1,000 more horsepower, and was almost twice as fast.

Two of the 17 Howard 500s built still fly today. Depending on your point of view, they both own, or are owned by, Tony Phillippi. Phillippi’s interest in aviation was inevitable. His father founded and ran an international construction business during World War II. Needing an airplane that could land in rough, short fields scraped into construction sites, the senior Phillippi traded a DC–3 for, of all things, a Northrop Delta. When Tony started his own business (TP Aero) providing cranes to huge building projects all over the planet, he, too, acquired airplanes to support it. Beech Barons, Cessnas, and Lockheed JetStars served Phillippi projects throughout the world, especially the Middle East.

Then, as Tony remembers, “I picked up a copy of Trade-A-Plane, which I almost never do, and saw a full-page ad for something called a Howard 500. It was at Anoka, not far from my home in Minneapolis, so I drove out to see it. We opened the hangar door about four inches, I saw those huge props, and I was toast.” He soon owned N500HP.

A few years later, he found a second 500 in the United Kingdom. The airplane had been sitting for a long time, but after a year of work, including sending the engines to Idaho for overhaul, it was ready to fly home. “As we worked on N500LN, we gained an even deeper appreciation for Dee Howard and his organization,” said Phillippi. “You could take a mechanical system, imagine the most elegant way possible to build it, and find it done just that way on the Howard. We flew back across the Atlantic without a hitch. We crossed Greenland in beautiful weather, the engines running perfectly, and saw a landscape that very few people get to see” (see a video of the trip at tpaero.com).

There may be cooler things you can do than get a ride in a Howard 500, but when you’re strapped into the cockpit jump seat and taxiing out, you can’t think of a single one.

Brian Rygwall and Ryan Mohr are sitting up front. Mohr grew up around airplanes—his father is a well-known airshow pilot—and although he flies airliners for a living, he’s flown dozens of antique and classic airplanes. Rygwall is a different story. He came to TP Aero as a mechanic and quickly made himself an expert on the complex systems in the Howard. His skill and work ethic got him into the cockpit and today, with a grand total of 800 hours or so, he’s competent in the Howard.

“I could make Brian a captain on the 500 in a weekend,” Mohr says, “but he’s too valuable in the right seat. Several pilots fly the airplanes occasionally, but Brian works on them full time and knows the systems better than anybody in the world. Having him as a co-pilot makes every pilot better and safer.”

Watching Rygwall—in the left seat this morning—and Mohr work together, it is easy to see what he means. The Howard is a complicated piece of machinery that requires teamwork to fly safely. Before takeoff, we add 125 gallons of 100LL to the inboard tanks (enough for about 35 minutes of flying) and 10 gallons of anti-detonation injection fluid (a mix of water, methanol, and lubricating oil meant to cool parts of the induction system in order to avoid premature ignition) to the tanks on the outside of the nacelle. With the cowl flaps open and the mixture lever aft, the starboard starter motor slowly cranks the big four-blade propeller around. After a few revolutions, Rygwall teases some combustion out of the cylinders with the primer. The blades blur and a few seconds later the mixture lever goes forward and the engine settles down to a smooth idle. With both engines running it is time to taxi.

The taxiways at Anoka are none too wide for an airplane the size of the Howard, so getting to Runway 18 takes concentration. “I avoid steering with the brakes.” Mohr explains, “They are crazy touchy. I tell new pilots to rest the tips of their shoes on the brake pedals and just move the hairs on their toes.”

The pretakeoff checklist and brief completed, Rygwall aligns the long nose with the runway centerline and brings up the power for a “dry” takeoff; in other words, no anti-detonation injection. Both props turn the same direction, and the left engine is running a generator that takes 65 horsepower. That, and the fact that the rudders don’t have much effect when the airplane is slow and tail down, means the pilot must bring in the left engine well before the right to keep the airplane on the centerline. Soon enough the tail comes up. Even with something like 4,000 horsepower being developed at 51 inches of manifold pressure, the acceleration is not blinding—after all, it’s pulling almost 15 tons. Once airborne, Rygwall keeps the nose relatively low, honoring the small oil coolers’ demand for forward speed, and retracts the gear. The wheels are in the wells three seconds later. Later, the pilots switch seats and Mohr dials up the anti-detonation injection for his takeoff. For the expense of about four gallons of water and methanol, the engines are run up to 59.5 inches of manifold pressure and develop an extra 400 horsepower—each. As he advances the throttles, Mohr leads with the left engine by 25 inches. The result is noticeably quicker acceleration and a shorter takeoff run.

Even though our flight takes place under a 3,000-foot ceiling, it is easy to see the virtues of traveling in a Howard. At moderate power we are indicating about 200 knots. At higher altitudes and power settings it will true better than 250 knots. In the days of 130-octane gasoline it could go faster yet. In the cockpit, the noise level is far below the average piston single. Back in the cabin where the quality sits, it’s library quiet. It’s hard to believe that 36 cylinders are pounding away just a few feet outside the picture window. From the pilot’s point of view, the manual ailerons feel heavier than the hydraulically boosted rudder(s) and elevator, but everything is well suited to the mission.

On landing, with the gear down (there are five independent ways to do that) and big flaps extended, the Howard settles into a stabilized approach at about 105 knots. Wheel landings keep the tail flying and the rudders effective. It takes some room to get all that weight and inertia slowed down. A 3,500-foot runway is short when you’re flying a Howard.

It’s on a long trip that the airplane really shines. Even though it’s old enough to draw Social Security, the Howard still has some advantages over more modern designs. Mohr compares it to a Beechcraft King Air 200: “The two airplanes are similar in speed and fuel burn, but the Howard has much longer range. We can easily make a trip from Anoka to Texas nonstop in the Howard, but we have to make a fuel stop in the King Air.”

There are other benefits no more modern airplane can match. For one thing, it’s just so much sexier than the generic white-tube-with-two-pods business jet.

“We’ve flown to major events and taxied up to ramps chock-full of high-end jets and turboprops. We usually get a parking spot right in front of the terminal and when those props stop turning, we’re surrounded,” Mohr says. “Forget the jets. Pilots, girlfriends, celebrities—everybody wants to look at the Howard.”

Despite its performance and elegant engineering, the Howard 500 never made it big in the business airplane world. It appeared just as turbine airplanes designed specifically for the role were emerging from major manufacturers, so a complex piston-engine taildragger was seen as (and probably was) an anachronism.

Even though it was late to the party, the sight and sound of a Howard 500 powering down the runway still turns heads and makes hearts beat faster. Thanks to its creator and the efforts of Tony Phillippi and his crew, it can create its own celebration.

Ken Scott is a freelance writer who builds and flies airplanes from his rural airpark home in Oregon.