AOPA’s 80th Anniversary: The foremost advocate

80 years of service to general aviation

Friedlander said that an organization should be formed to represent the interests of private airplane manufacturers. Wolf said the same thing about general aviation pilots: “I think the private pilots would need a professional organization shortly. Certainly their flight interests must be represented by a better lobby or they will be overshadowed by the airlines at all the capitols.” Wolf’s reference to a “better” lobbying organization alludes to the disorganized state of general aviation at the time, called “miscellaneous aviation” in those days. Enthusiasts had their choice of joining several organizations, such as the Private Fliers Association and the Sportsman Pilots Association, but neither showed any real interest in advancing initiatives on behalf of their members—or the general aviation community at large.

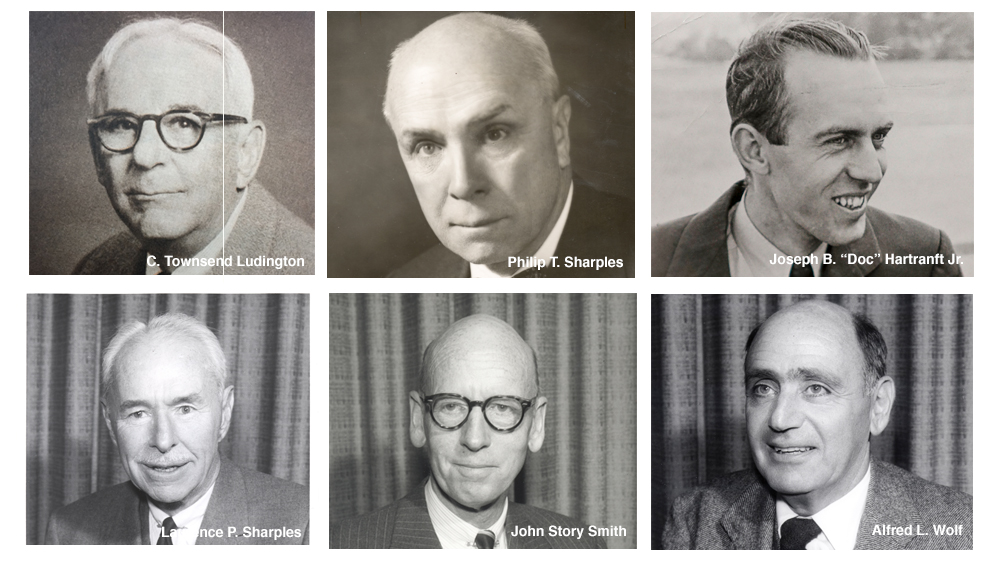

Four other Philadelphia lawyer-pilots joined Wolf in planning sessions aimed at creating a new association. They were Charles Townsend Ludington, the brothers Laurence P. and Philip T. Sharples, and John Story Smith. These five, while hosting Civil Aeronautics Authority Chairman Edward J. Noble on a turkey-hunting expedition in southern Georgia, received considerable encouragement when Noble said that military and airline groups usually got their way when lobbying the CAA, presenting their arguments in a professional, convincing manner. General aviation pilots appeared at the CAA individually, with oddball demands and opinions that got nowhere. By May 15, 1939, AOPA’s five founders had drawn up the association’s charter and filed its incorporation papers. Ludington was named president and AOPA was born, with its goals being to make flying “more useful, less expensive, safer, and more fun.”

AOPA’s first employee was Joseph B. “Doc” Hartranft Jr., a recent University of Pennsylvania graduate who had organized a collegiate flying club. Wolf hired him to recruit the first members and start a newsletter that would publicize AOPA’s initiatives. A deal was struck with the Ziff-Davis publishing company to put an insert in Popular Aviation magazine (later to be renamed Flying and Popular Aviation and then simply Flying magazine). The magazine including the four-page insert would be sent to AOPA members. By the end of 1939, some 2,000 charter members had signed up.

Hartranft had a small staff based in Chicago, near Ziff-Davis’ offices, and they worked on the insert and lobbying efforts. One was to support the formation of the Civilian Pilot Training Program, which funded pilot training for thousands who would go on to serve as military pilots in World War II. The fledgling AOPA also secured a reduction in medical examination fees and began an ongoing drive to promote the design of safe and simple general aviation airplanes—like the Ercoupe—with the goal of reducing the large number of stall/spin accidents.

AOPA Sweepstakes

- 1956 Piper Tri-Pacer Champion Sky-Trac

- 1957 Champion Tri-Traveler (Second prize was a Spartan Sprite boat)

- 1958 2 Forney Aircoupes (promotion for Hertz)

- 1989 Piper Archer

- 1993 Good as New Cessna 172

- 1994 Better than New Cessna 172

- 1995 First New Cessna 172

- 1996 First New Cessna 182 Skylane

- 1997 Ultimate Piper Arrow

- 1998 Timeless Tri-Pacer

- 1999 Aero SUV Cessna 206

- 2000 Millennium Mooney 201

- 2001 Bonanza V35

- 2003 Centennial of Flight Waco UPF-7

- 2004 Win A Twin Piper Twin Comanche

- 2005 Commander Countdown

Rockwell Commander 112 - 2006 Win A Six in ’06 Piper Cherokee Six

- 2007 Catch A Cardinal Cessna 177B

- 2008 Get Your Glass Piper Archer

- 2009 Let’s Go Flying Cirrus SR22

- 2010 Fun to Fly Remos GX

- 2011 Crossover Classic Cessna 182

- 2012 Tougher than a Tornado Aviat Husky

- 2014 Beechcraft Debonair

- 2015 Reimagined Cessna 152

- 2017 Cessna 172

- 2019 Piper Super Cub

AOPA Milestones over 80 years

AOPA Milestones

AOPA milestones (below) include headquarters moving from Philadelphia to Chicago; New York City; Washington, D.C.; and Bethesda, Maryland; before settling at its current location at the Frederick, Maryland, Municipal Airport.

C. Townsend Ludington

1939: May 15, 1939, AOPA is founded. Membership reaches 2,000 by the end of year one. Headquarters starts off in Philadelphia, then, once a deal with Ziff-Davis is signed, moves to the Transportation Building in Chicago. “AOPA News,” soon to become “AOPA Section,” first appears in Popular Aviation.

- 1940: AOPA Air Guard is formed. Membership reaches 4,000 by March.

- 1942: Headquarters moves to the Carpenters Building in Washington, D.C.

- 1943: “AOPA Section” is replaced by “AOPA Pilot” inserts in what had become Flying magazine.

- 1945: AOPA headquarters moves from K Street to F Street into the International Building in D.C.

- 1946: Membership reaches 20,000.

- 1947: Headquarters moves to the Washington Building on New York Avenue NW in D.C.

- 1948: Membership hits 50,000.

- 1950: The AOPA Foundation is created as a nonprofit organization dedicated to GA safety and pilot education.

- 1951: AOPA headquarters moves to the Keiser Building on East-West Highway in Bethesda, Maryland.

Joseph B. "Doc" Hartranft

- 1956: Membership hits 80,000.

- 1958: AOPA Pilot magazine makes its debut as an independent magazine with publication of the March 1958 issue.

- 1961: The first AOPA Airport Directory is published, later known as AOPA’s Airports USA.

- 1962: International Council of Aircraft Owner and Pilot Associations, now IAOPA, started by “Doc” Hartranft and Victor Kayne.

- 1965: Membership reaches 111,371. AOPA Pilot carries first aircraft and engine directory.

- 1967: AOPA Foundation becomes AOPA Air Safety Foundation to reflect its work.

- 1969: Membership grows to 148,000.

- 1972: AOPA headquarters moves to the Air Rights Building on Wisconsin Avenue in Bethesda, Maryland

John L. Baker

- 1978: Membership hits 220,000.

- 1979: Membership grows to 242,000.

- 1980: AOPA forms a Political Action Committee.

- 1983: In May, AOPA headquarters moves from Bethesda to Frederick, Maryland, at the Frederick Municipal Airport. Membership is up to 269,000.

- 1985: Membership is at 258,000.

- 1989: Membership reaches 301,000.

Phil Boyer

- 1992: Membership hits 303,000.

- 1993: AOPA Online is introduced on CompuServe.

- 1994: Project Pilot is launched to boost student pilot starts. General Aviation Revitalization Act (product liability reform legislation) is signed in August. Membership is up to 336,000.

- 1995: AOPA Online launches a comprehensive website in December.

- 1997: AOPA Airport Support Network is launched. Membership reaches 341,000.

- 1998: AOPA purchases Flight Training magazine.

- 1999: AOPA’s first issue of Flight Training magazine is published in April. ePilot email newsletter launches. Membership reaches 350,000.

- 2000: Membership hits 365,000.

- 2001: Terrorist attacks on September 11 ground all civil aviation. AOPA is instrumental in GA’s return to flight.

- 2002: Membership reaches 390,000.

- 2003: Meigs Field is closed surreptitiously. Membership is up to 400,000.

- 2005: Membership reaches 406,000.

- 2006: Project Pilot is relaunched with spokesman Erik Lindbergh, Charles Lindbergh’s grandson. Membership is up to 409,000.

- 2007: AOPA Foundation, a 501(c)(3) organization, is incorporated. Membership: in June—411,000, in December—413,000.

Craig Fuller

- 2008: Let’s Go Flying program is launched.

- 2009: Aviation eBrief rolls out. AOPA Live premieres at AOPA Aviation Summit in Tampa, Florida. GA Serves America launches. Membership hits 415,000.

- 2010: AOPA starts Flight Training Retention Initiative. AOPA Air Safety Foundation is renamed the AOPA Air Safety Institute.

- 2012: Pilot’s Bill of Rights signed into law August 3. AOPA petitions FAA for driver’s license medical standard.

Mark Baker

- 2013: Membership is at 358,000.

- 2014: You Can Fly initiative is established, along with Rusty Pilots and Flying Clubs.

- 2016: FAA Extension, Safety, and Security Act of 2016 (establishing BasicMed) is signed. Membership stabilizes at 312,000.

- 2017: BasicMed goes into effect in May. Membership is at 313,000.

- 2018: High School Aviation Curriculum begins rollout to schools. Membership hits 318,000.

In 1940 the first AOPA Units—local pilot groups organized by members—were established, starting with a unit in Washington, D.C. The number of units across the nation reached 175 by the early 1950s. Meanwhile, AOPA membership reached the 4,000 mark by March 1940. A strong membership was—and remains—vital to AOPA’s clout, and in 1940 this translated into successful fights against hikes in landing fees at New York’s La Guardia Field and others. The association also established an Emergency Pilot Registry and formed the AOPA Air Guard—efforts to train pilots to fulfill emergency functions in times of war and national disaster. When the United States entered World War II, AOPA also helped register pilots as required by the federal government, and at the same time fought for access to coastal airspace that would have been otherwise prohibited to general aviation pilots. The association served in a liaison role between civilian pilots and military authorities during the war, ensuring reasonable access to the growing amount of military training airspace.

After the war, the general aviation pilot population grew, and AOPA membership with it. By 1946 there were 20,000 members. Attention turned to new navigation aids—VORs—that would add significant cost and weight to small aircraft. AOPA fought for and won measures to make sure VOR use was implemented gradually. In the safety arena, AOPA endorsed the installation of stall warning indicators on all airplanes and secured a discounted price for those members wanting to have the Safe Flight Instrument Corporation’s new electronic stall warning indicators. What became today’s Malfunction and Defect Reports were initiated by AOPA in 1948.

By the time general aviation entered its boom time in the 1950s, AOPA formed the AOPA Foundation to advance aviation safety; it would later evolve into today’s AOPA Air Safety Institute. To help prevent midair collisions in airport traffic patterns, AOPA proposed using a single frequency for universal communications—unicom, on 122.8 MHz—so that pilots could inform each other of their locations.

In March 1958, the first issue of AOPA Pilot magazine was published, marking the association’s debut as a publisher independent of the 1939 Ziff-Davis agreement.

The 1950s and 1960s were times of immense growth in airline traffic, leading to growing conflict with general aviation. Proposals emerged with the intent to deny or exclude general aviation aircraft from larger airports by forming what were initially called High Density Air Traffic Zones, which ultimately led to today’s Class B, C, and D airspace. AOPA sought, and gained, concessions favorable to general aviation.

“The world of the airline plane, and the world of the military plane, was a different world than the one in which Carl was making his Aeroncas.” —Alfred L. WolfDebate intensified over the best way to manage increasing air traffic after the June 30, 1956, midair collision of a United Airlines DC–7 and a Trans World Airlines Constellation over the Grand Canyon. The era of rapid terminal airspace expansion and radar-based air traffic control had begun, and with it the mandatory installation of transponders on all aircraft operating in much of the U.S. airspace. As with the 1955 military attempt to force adoption of TACAN instead of VOR/DME (co-located vortacs ended up being the solution, at AOPA’s insistence), AOPA argued for a more gradual phase-in of transponder use, arguing that the technology wasn’t yet capable of being fully implemented.

But if there were gains, there also were setbacks. Elwood R. Quesada and William F. McKee, Federal Aviation Administration administrators in the 1960s, presided over airport closures, funding fights, and airspace denials, while high-profile midair collisions—involving both airliners and general aviation airplanes—prompted government recommendations for faster, mandatory implementation of transponders and new, stricter-access airspace called Terminal Control Areas (TCAs) around busier airports. Pointing out that the airliners were at fault, AOPA recommended dedicated climb and descent corridors for high-performance airplanes and pushed for a proximity warning indicator that could alert airplanes to nearby traffic. This idea was to become a reality with traffic alert and collision avoidance system (TCAS) equipment and other collision avoidance technologies we use today. Ultimately, the TCA concept prevailed. Today, it’s known as Class B airspace.

But if there were gains, there also were setbacks. Elwood R. Quesada and William F. McKee, Federal Aviation Administration administrators in the 1960s, presided over airport closures, funding fights, and airspace denials, while high-profile midair collisions—involving both airliners and general aviation airplanes—prompted government recommendations for faster, mandatory implementation of transponders and new, stricter-access airspace called Terminal Control Areas (TCAs) around busier airports. Pointing out that the airliners were at fault, AOPA recommended dedicated climb and descent corridors for high-performance airplanes and pushed for a proximity warning indicator that could alert airplanes to nearby traffic. This idea was to become a reality with traffic alert and collision avoidance system (TCAS) equipment and other collision avoidance technologies we use today. Ultimately, the TCA concept prevailed. Today, it’s known as Class B airspace.

By 1980, thanks to its 245,000-strong membership and its persistent advocacy, AOPA had earned greater respect as a major aviation lobbying presence. It needed this clout to earn concessions to anti-general aviation measures involving fuel price hikes and availability, diversion of Airport and Airway Trust Fund money to the general fund, flight restrictions following the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) strike of August 1981, and a product liability crisis that manufacturers claimed was responsible for inflation in the price of new airplanes—and their curtailed production. As for the latter situation, AOPA was central in creating the General Aviation Revitalization Act of 1994, which put an 18-year statute of repose on legal actions against those seeking damages from aircraft accidents.

The hints of another challenge had been surfacing since the early 1980s, when the pilot population peaked at 827,071. By 1990 it was down to 702,659, and still dropping. Under President Phil Boyer, several initiatives were begun with the aim of bringing more people to the cockpit. Project Pilot launched in March 1994 with the goal of boosting student pilot starts, and 9,000 student pilots participated that year under the guidance of Project Pilot mentor pilots; the program expanded in 2006 to include web tools and resources and later led to such programs as Let’s Go Flying in 2008. AOPA also partnered with other general aviation interest groups and contributed to Be A Pilot, an industrywide pilot recruitment campaign.

Handheld GPS navigation units came on the scene in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and it wasn’t long before AOPA took the lead in lobbying for GPS as a primary source of navigation data, including instrument approaches under instrument flight rules. After a trial period where GPS course information was superimposed over conventional ILS, VOR, and NDB guidance, the first standalone GPS approach was approved in July 1994. Boyer and FAA Administrator David Hinson flew the GPS approach to Runway 5 at AOPA’s home base at the Frederick, Maryland, Municipal Airport.

Funding issues began to surface in earnest in the 1990s, with many in Congress calling for user fees to pay for the modernization of an aging aviation infrastructure. Traditionally, the Airport and Airway Trust Fund—fed by aviation fuel taxes, airline ticket taxes, and other sources—covered aviation infrastructure and upgrades. But this wasn’t enough to cover increased expenses, some said, so pressure was increasing for user fees (for landing, navigation, and other ATC and FAA services) to make up the shortfall. In truth, much of the trust fund money was diverted for nonaviation purposes, and AOPA argued that there was plenty of money left in the trust fund—if only it could be released from the spending caps then in force. In April 2000, President Bill Clinton signed AIR-21, the Aviation Investment and Reform Act for the Twenty-First Century, and the FAA received the necessary $40 billion over the following three years.

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, set the tone for much of the following years. For general aviation this meant, after an initial grounding of all flights for three days following the attacks, a series of airspace restrictions and operational restrictions. And every step of the way, AOPA advocated for pilots’ interests, whether it was help in returning to their home airports, providing graphic illustrations of sensitive airspace around nuclear power plants, or arguing for procedures that allowed expanded access to Class B.

The number of FAA-certificated pilots peaked at 827,071 in 1980. Student pilot numbers had already begun to slip.AOPA had been largely successful in deterring airport closures, but a huge exception occurred in March 2003 when Chicago Mayor Richard Daley ordered the sudden closure of Merrill C. Meigs Field by having large “Xs” carved into its runway by bulldozers. Daley had been threatening to close it since the late 1980s, and AOPA had been successful in keeping it open by encouraging local pro-airport activists. But despite an agreement by Daley and Illinois Gov. George Ryan to keep Meigs open until 2026, Daley made his abrupt move under the cover of darkness.

Under President Craig Fuller’s term of service (2008-2013), AOPA forged important new relationships with other general aviation groups, including the Experimental Aircraft Association, in the interest of providing a united front in political and regulatory battles. AOPA also expanded efforts to boost the still-sagging pilot population with its Center to Advance the Pilot Community, which supported the development of a network of flying clubs, established awards honoring instructors and flight schools, and laid the groundwork for other initiatives that continue today under the You Can Fly program.

Believe it or not, user fees crept back up as an issue when President Barack Obama proposed budget cuts and wanted user fees to make up the difference in the FAA’s budget. Fuller’s extensive government experience, including service as chief of staff to then-Vice President George H.W. Bush in the Reagan administration, was vital in this and other political fights during his term.

Today, AOPA puts renewed energy into building the pilot community. Under President Mark Baker, AOPA began its You Can Fly program in 2014. This multi-pronged effort, funded by donations to the AOPA Foundation, includes Rusty Pilots seminars designed to bring lapsed pilots back into the fold; a Flying Clubs initiative to create and support flying clubs; a High School program that offers scholarships and a STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) curriculum focusing on aviation; a Flight Training program with awards and resources aimed at supporting flight schools and CFIs; and a network of AOPA ambassadors that visit airports and give boots-on-the-ground contact in support of all the You Can Fly goals. More than 6,200 lapsed pilots have resumed flying after attending Rusty Pilots seminars, and the Flying Clubs initiative has launched more than 100 flying clubs. We’ve had more than 19,000 responses to the Flight Training Experience Survey, and in 2018 You Can Fly honored 128 CFIs and 83 flight schools as part of the Flight Training Experience Awards. More than 3,000 students have used AOPA’s Aviation High School STEM Curriculum, and AOPA will award $1 million in scholarships to high school students and teachers this year, thanks to a grant from the Ray Foundation.

“It will take thousands of pilots, not millions, to reinvigorate GA. Together we can do this. We have to do this.” —AOPA President Mark BakerThanks to decades of AOPA efforts on medical certification reform, BasicMed went into effect in May 2017. This simplified way of obtaining medical certification to fly recreationally allows pilots to fly single- or twin-engine aircraft capable of flying up to 250 knots and 14,000 feet, having maximum takeoff weights up to 6,000 pounds and up to six seats, including those with retractable gear. By visiting any state-licensed physician every four years, making logbook entries, and taking an online course every 24 calendar months, BasicMed offers pilots the option to work with their personal doctor and save the hassle of visiting an AME. The response was immediate: After one year, 30,000 pilots qualified to fly under BasicMed.

As always, recent history has continued to provide ongoing examples of efforts to close general aviation airports, put a dollar value on access to services already adequately funded by existing taxes, restrict airspace access, raise fuel prices, and even charge exorbitant rates for the most temporary use of ramp space at FBOs. In this sense, the same issues face general aviation over and over, decade after decade.

But history also shows that AOPA continues to fight for pilots’ access to airports and airspace, and to make flying more useful, less expensive, safer, and more fun. So it will be in the future, as the association continues to advance general aviation’s cause in the name of all pilots, whether they are members or not.

Email [email protected]

Read more about AOPA and the history of general aviation in America in Freedom to Fly, a coffee-table book commemorating AOPA’s eightieth anniversary. Buy it online for $39.95.

Read more about AOPA and the history of general aviation in America in Freedom to Fly, a coffee-table book commemorating AOPA’s eightieth anniversary. Buy it online for $39.95. Will fly for pancakes

Will fly for pancakes