Never Again: I do declare

‘Mayday’ as a stress-reduction technique

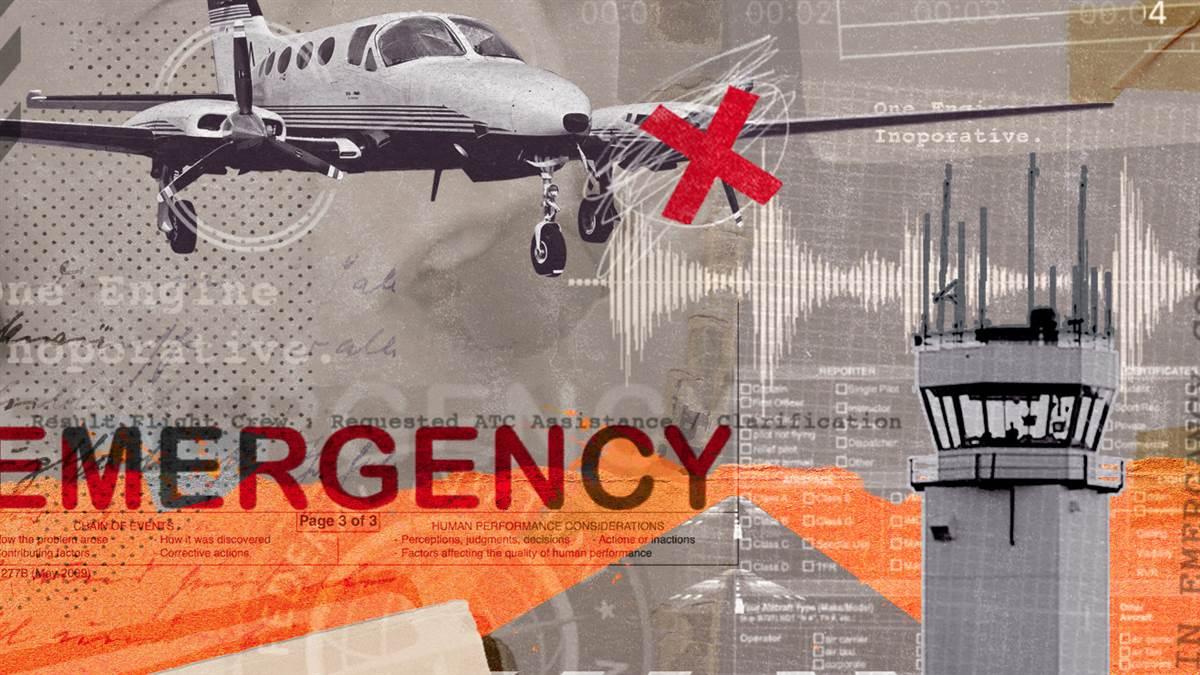

I recently made a rare one-engine-inoperative (aka engine-out) landing. In thousands of hours of flying twin-engine airplanes this was only the second time.

The first time, many years ago in a Piper Seneca II, I did a precautionary shutdown because a propeller deice boot was separating from the blade. I was getting VFR flight following but did not tell ATC because I didn’t want to deal with the paperwork. I ran the good engine pretty hard so I could keep up a reasonable speed and not invite any questions. The landing on the not-so-long home-base runway was a surprise because the feathered engine didn’t have the drag to help decelerate on landing.

Reflecting on the episode later, I concluded I handled it poorly. My reluctance to declare an emergency was based on the fear of having to do paperwork. It occurred to me I had no idea what paperwork would be required, and I had never heard of anyone who had actually had to deal with the paperwork. More important, I had thrown away the opportunity to have ATC watching over me. Beyond that selfish reasoning, I also essentially deceived ATC by letting them believe my airplane could perform like a normal aircraft of its type, when in fact I was already getting all I could from my wounded bird. I vowed if it ever came up again I would make ATC part of my team.

The second one-engine-inoperative landing happened recently in a Cessna 414A. While transitioning for the approach I noticed the left manifold pressure was not decreasing as I pulled back the throttles. I played around with throttle, rpm, and mixture controls to evaluate what I was dealing with. I concluded that I had no control over the throttle, and I had one power setting available on that engine, which was about 25 inches of manifold pressure.

Ordinarily you’d think having partial power is better than no power. For the moment that was so, but as I was intercepting the final approach course I started thinking about the landing. I’d never landed an airplane with nearly cruise power on one engine. I decided to revert to something I did know how to do: a single-engine landing.

At this point I was nearing glideslope capture. It was visual conditions, daytime, going into my home airport. In the past I probably would have just feathered the engine, intercepted the glideslope, dropped the gear, and motored in. But I got to thinking how the accident report would read and decided I needed to edit the script. I wanted to take more time to prepare and make sure I did not generate an accident report in the first place. I wanted to run the shut-down checklist, get configured, and brief the single-engine landing. In addition, a considerable amount of traffic was departing and approaching the Class D airspace and in the pattern for the parallel runways.

I reported to the tower controller I had an engine problem and I was shutting it down. I canceled IFR, declared an emergency, and told the tower I was breaking off the ILS to do a wide three-sixty to rejoin the localizer and continue for landing. I thought the 2 to 3 minutes for my three-sixty would be enough time to secure the offending engine and review the single-engine approach checklist, and the Mayday would get the tower controller to clear the path to the runway.

And that’s how it went down. I was able to progress at my pace with no “best forward speed” or “reduce speed to...,” no worries about whom to follow or if the airplane for the parallel runway would overshoot its final approach course, no vehicles crossing the runway. It was all rather stress-free.

The landing was uneventful but a bit longer than usual because of the lack of drag on the feathered side and partial flap (I didn’t feel the need to change configuration and I knew I had enough runway). The hardest part was taxiing to the hangar on one engine.

Oh, the paperwork? I did get a request to call the tower while taxiing in. They wanted to know if we were all OK. (I did file a NASA Aviation Safety Reporting System report just to be on the safe side.)

I hope you never have a problem but if you do, my suggestion is to declare an emergency and let ATC treat you like you’re Air Force One. AOPA

Pierre Wildman is an airline transport pilot living in Danville, California.