Proficiency: No equations required

The secret of flight doesn’t need to be

It was the same anticipation I experienced as a child when I had amassed enough breakfast cereal box tops to send in and claim my prize. Invariably, though, my hopes were dashed when a flimsy piece of plastic or some other throwaway arrived in the mailbox. Despite this poor track record, I still deemed the video collection worth the risk. At worst, I would see the way aerodynamics was explained in the olden days, and I’d learn a bit of history. When the envelope from University of Iowa arrived, I ran to put the disc in the DVD player and found the contents of this time capsule far better than I ever could have imagined.

It was the same anticipation I experienced as a child when I had amassed enough breakfast cereal box tops to send in and claim my prize. Invariably, though, my hopes were dashed when a flimsy piece of plastic or some other throwaway arrived in the mailbox. Despite this poor track record, I still deemed the video collection worth the risk. At worst, I would see the way aerodynamics was explained in the olden days, and I’d learn a bit of history. When the envelope from University of Iowa arrived, I ran to put the disc in the DVD player and found the contents of this time capsule far better than I ever could have imagined.

Lippisch was a German aerodynamicist whose important contributions included work on the delta wing, tailless aircraft, and high-performance gliders. In 1946, he immigrated to the United States as part of Operation Paperclip, the same program that brought more than 1,600 German scientists, including Wernher von Braun, to propel American flight research. In 1950 Lippisch began a 14-year tenure with the Collins Radio Corporation, during which time he published scientific papers on his smoke tunnel experiments and aeronautical innovations. In 1955, he created The Secret of Flight film series with the University of Iowa.

The series consists of 13 half-hour episodes in which Lippisch uses simple physical models and smoke tunnel videos that allow the viewer to witness the way wings produce lift, how they stall, and the nature of induced drag, to name just a few. The best part is, despite being at the top of his field, Lippisch targets a viewer with no technical background and introduces few scientific terms and equations. During the first episode alone, I realized I had been duped regarding the story of lift by the manuals I had studied as a student pilot.

I knew about the principle that eighteenth-century mathematician and physicist Daniel Bernoulli observed about fluid flow—when the velocity of the flow increases, the pressure it exerts decreases. It follows from Newton’s Second Law of Motion, which says the rate of change of momentum of a body is proportional to the force applied and in the direction of the applied force. But these facts don’t provide an intuitive understanding of lift, so some instructors and authors try to offer one.

The “equal transit theory” is a popular one that goes like this: Consider two air particles that start at the front of a cambered airfoil with one of them traveling across the top and the other below. Since the top surface of the airfoil is longer, the particle that travels across it must move faster in order to meet up with the particle that travels below. It’s a tidy theory, and perhaps it’s somehow romantic to think these long-lost particles will reconvene following their solo journeys. The trouble is, it’s just plain wrong, and the negative effects of teaching this flimsy theory last longer than the disappointment of a useless toy. Student pilots become flight instructors who propagate this fallacy through the aviation community at an alarming rate.Last year, several aviation authors offered mea culpas for presenting the equal transit theory. But one author defended its use by claiming that understanding what really causes lift necessitates learning big confusing words. Not true at all, as Lippisch deftly demonstrates.

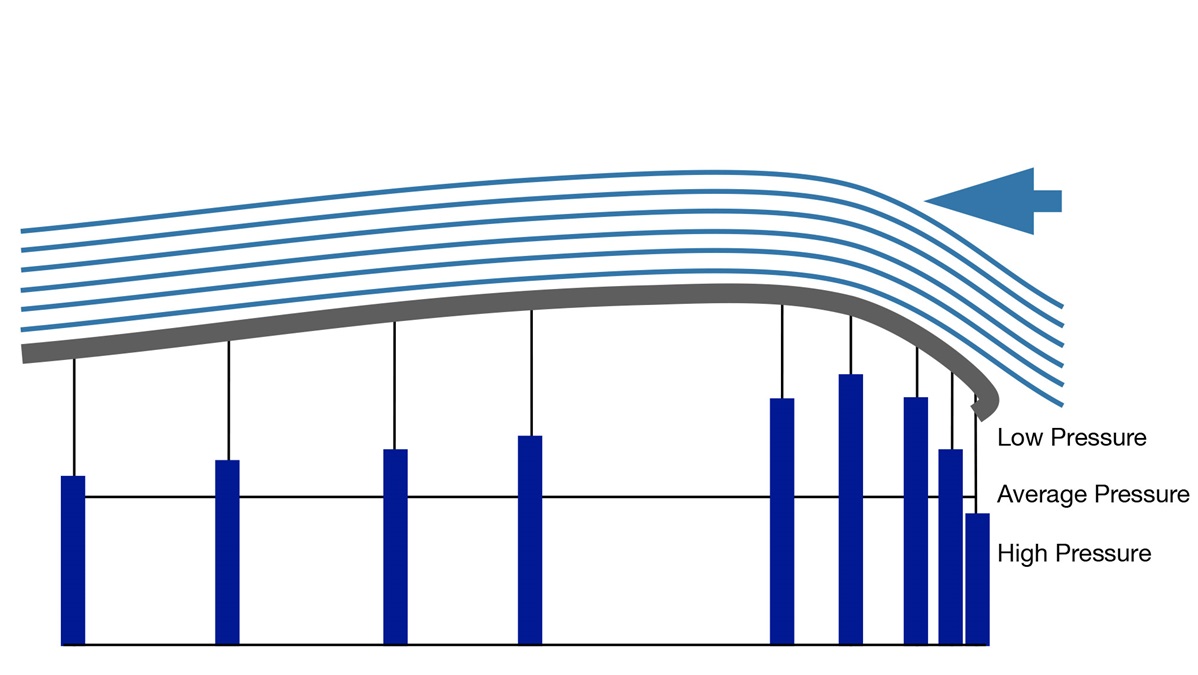

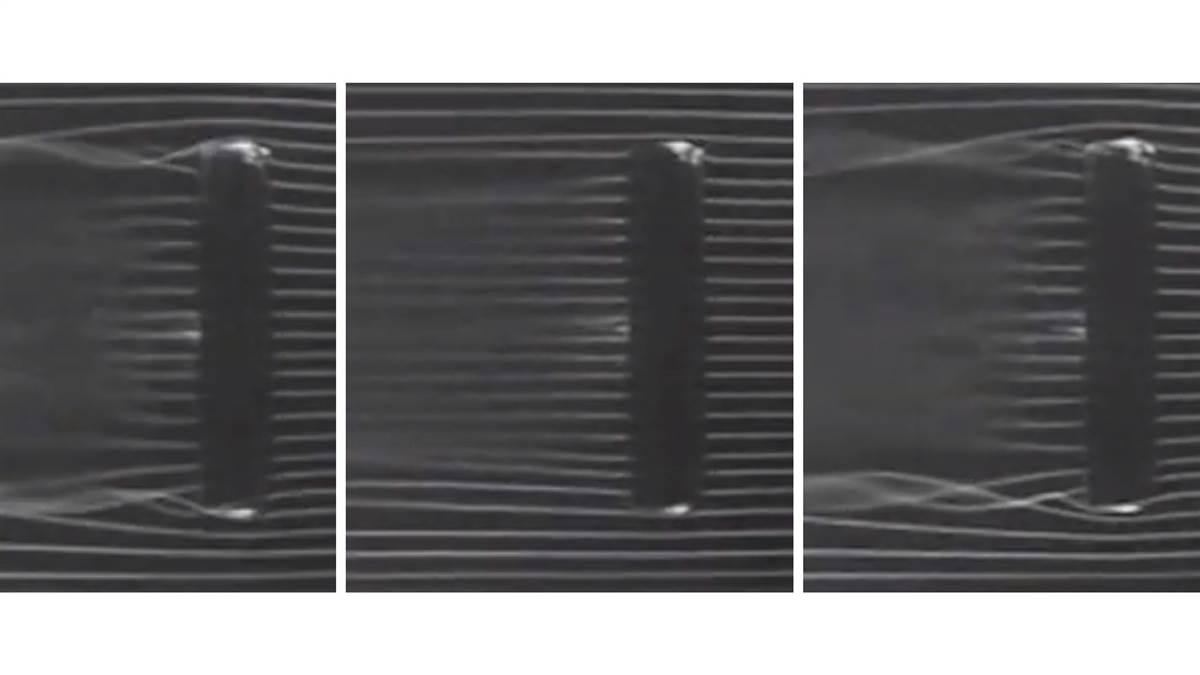

The Secret of Flight allows the viewer to actually witness the production of lift. Lippisch uses a wind tunnel in which a vertical strip with evenly spaced holes emits colored particles (or smoke) into the flow. The smoke along the streamlines reveals the shape of the flow around the airfoil. Many of the videos feature pulsated smoke to show the time history of the flow as well. The timelines prove that the flow across the top of the wing is much greater than the flow along the bottom. Those two air particles of the equal transit theory will never meet again! Note also that faster flow corresponds to streamlines that are more closely spaced. Finally, Lippisch uses a gas manometer to show the pressure is lowest along those regions of the airfoil at which the velocity is highest. Therefore, narrow streamlines correspond to faster flow which, in turn, results in lower pressure. With low pressure above the wing and high pressure below it, lift is the net force in the upward direction. That’s it!

All this represents just a few minutes of The Secret of Flight video series. Other highlights include the nature of a wing stall (above) and a visualization of induced drag via wingtip vortices (p. 86). In Episode 6, Lippisch starts with a simple propeller, increases its efficiency by enclosing it with a shroud, and then ultimately motivates the modern jet engine. In Episode 12, he explains why the smooth wings on a bird and the rough wings on an insect each minimize drag. These are just a few of the topics guaranteed to fascinate student pilots and aerodynamicists alike.

The Secret of Flight is indeed a time capsule produced when color films were rare. I chuckled when Lippisch predicted that “rocket engines will someday take man to space.” But while the age of the series is evident in quaint ways, the laws of aerodynamics are timeless; it’s our attempts to model and understand them that evolve over time. These smoke tunnel videos and simple demonstrations are as valuable as instructional tools today as ever. I have watched the series several times and I glean new facts with each viewing.

In recent years, The Secret of Flight became unavailable for purchase after the supply of DVDs was exhausted. But in August of this year, the University of Iowa bestowed upon the aviation community an incredible gift by uploading the series in its entirety on YouTube. No money, anxious waiting times, nor impending disappointment is necessary. Just sit back, relax, and enjoy as the secret of flight is revealed.

Catherine Cavagnaro is an aerobatics instructor and professor of mathematics at Sewanee: The University of the South.

SEcret of Flight