What went wrong? Pattern of confusion

Situational awareness degrades, traffic converges at busy airport

Pilots develop situational awareness in layers: first, situational awareness inside their own cockpit; then in the immediate vicinity of their airplane; and, finally, in the extended area. The stronger a pilot’s situational awareness, and the broader it expands, the better the decision making. Instructors look for advancing situational awareness during student training, especially in the traffic pattern, prior to solo. Pilots must develop the ability to fly the airplane while using eyes and ears to build a mental picture of the flow of operations and where they fit in the big picture.

Air traffic controllers build careers on their ability to develop, maintain, and regain situational awareness in increasingly complex environments. A few hours in an ATC facility usually ends in admiration for the remarkable situational awareness controllers gain and maintain under dynamic and intense conditions. In local (tower) operations, controllers combine radios, sight picture, and sometimes radar displays to build the situational awareness needed to sequence pattern traffic safely.

On a cloudless morning with light winds and excellent visibility, a breakdown in situational awareness at multiple points in the Class D environment at Brown Field Municipal Airport (SDM) in San Diego resulted in a Sabreliner jet colliding with a Cessna 172 on base leg. Both airplanes were destroyed; the lone occupant/pilot of the Cessna 172 was killed, as were all four people aboard the Sabreliner. At the time of the accident, nine aircraft were under tower control, including two jets, several piston airplanes of differing capability, and a helicopter. A right traffic pattern was in effect for both parallel runways, which can add risk but is common for SDM because of its proximity to the Mexican border and Tijuana International Airport.

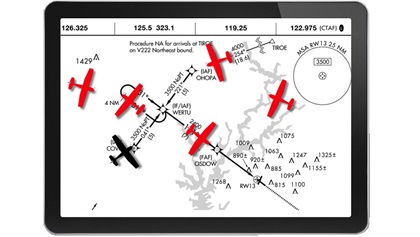

A controller with 37 years’ experience had just taken control from a trainee struggling with a full pattern when the Sabreliner entered on a right downwind to Runway 26R, closing rapidly on the mishap 172, which was on a tighter downwind, forward and to the right of the jet. Seeing a conflict, the tower controller issued directions for the 172 to make a right three-sixty, toward the runway and away from the Sabreliner—but the controller issued the instructions with an incorrect call sign. Meanwhile, 3 miles away, forward and to the left of the Sabreliner, a puzzled pilot in a different 172, exiting the pattern and no conflict to anyone, obediently started a right 360-degree turn. The Sabreliner passed off the left side of the mishap 172, which continued its pattern to Runway 26R. The Sabreliner turned base and about the time the controller realized the conflict, the Sabreliner rammed the 172 while overtaking it, critically disabling both airplanes.

Illustration by Charles Floyd

In its extensive report, the NTSB cited the tower controller’s incorrect call sign usage as probable cause with loss of situational awareness as a contributing factor. The loss of situational awareness extended beyond the tower controller and included the mishap pilots and other pilots in the pattern. Why? What factors contributed to a veteran controller, two ATP pilots with several thousand hours each in the Sabreliner, a 172 pilot with a few hundred hours, and others all losing situational awareness?

Loss of situational awareness is frequently caused by incorrect, missing, or an overload of information. All three contributed to the accident at SDM. The veteran controller combined ground and local (tower) operations under control of a trainee he was supervising. The pattern got busy quickly and the trainee, operating sufficiently at first, quickly exceeded his limits. The experienced controller took over, but never fully established situational awareness. Missing information, he made erroneous transmissions, which confused pilots and degraded their situational awareness, further contributing to confusion all around.

Excellent learning happens when students push their limits, make mistakes, and work their way out of them, while instructors supervise. Think of a CFI who sees an impending stall developing because of a student’s inattention and allows the situation to progress to the stall warning horn—a lesson in distraction the student will long remember. In the SDM tower that day, the instructor controller allowed the situation to degrade so much that the instructor himself lost situational awareness and ultimately could not salvage the situation before disaster ensued.

Mental mistakes, missed communications, inability to process new information, and irritation all are warning signs of degrading situational awareness. In this scenario, the instructor controller exhibited most of these. He provided erroneous instructions to multiple aircraft, frequently corrected himself, and spoke sharply to a helicopter in the pattern. In such situations, it’s vital to recognize symptoms of degrading situational awareness and take immediate action to gain time or distance to regroup and rebuild a full and accurate mental picture.

The unorthodox pattern that day, full of widely dissimilar airplanes and a flustered controller, would have been a difficult place for pilots to build and maintain situational awareness. Sitting at zero knots and 1 G, it’s easy to identify all the miscues, recognize a degraded environment, and list steps that pilots could have taken: holding outside of the Class D, exiting the pattern, requesting an extended downwind, correcting errant call sign use, verifying puzzling instructions. Any of these may have helped gain time and distance, rebuild situational awareness, and broken the accident chain.

Instead, the pilots pressed on, trying to work through it. The Sabreliner crew appeared to make no adjustments in their cockpit to compensate for a controller they described as “panicking.” The pilot of the 172 likely heard the tower controlling the Sabreliner, heard the Sabreliner being directed to turn base, and yet showed no sign of questioning the situation. The 172 pilot exiting the pattern, when given a nonsensical instruction, made no attempt to confirm the guidance and blindly executed the maneuver. A pause, a question, a request for confirmation, or an increase in vigilance in any of these cockpits may have changed the outcome.

Few things are more dangerous to a pilot than a loss of situational awareness. If warning signs were easy to identify, degraded situational awareness would be easier to deal with—but loss of situational awareness usually occurs in confusing situations, often with abundant and erroneous information. Our best defense is to be alert for the warning signs in ourselves and in others, and take action when we recognize it. Find a way to gain time and distance and rebuild an accurate mental picture of what’s going on around us.

Email [email protected]

The AOPA Air Safety Institute video Collision Avoidance: See, Sense, and Separate recommends ways to improve your situational awareness through listening and scanning techniques. The video also explores ATC assistance and limitations in a non-radar environment.

The AOPA Air Safety Institute video Collision Avoidance: See, Sense, and Separate recommends ways to improve your situational awareness through listening and scanning techniques. The video also explores ATC assistance and limitations in a non-radar environment.