Opinion: Savvy Maintenance

Fresh annual: Why it’s no substitute for a proper independent prebuy

“Part of my deal with the previous owner was that he would have a complete annual inspection performed and any airworthy discrepancies corrected before I took delivery,” Dan said in his email. “The annual was completed with no squawks in mid-February and I flew it back from Texas in early March.

“The airplane seemed OK on the ferry flight to California,” Dan continued, “except for the rate of climb, which was averaging only 300 to 500 feet per minute. I guess we didn’t really notice it since all the airports we used had long runways. But my home field has a 3,300-foot runway and on takeoff the airplane barely clears the trees at the end of the runway.

“The airplane is grounded,” Dan reported, “and the engine needs to be torn down.”“I rented a similar airplane and its rate of climb was much better. I also became aware that there was a minimum static rpm specification of 2,275 rpm—I knew nothing about this before—and my Warrior can only make 2,200 rpm on a good day when leaned for maximum rpm.”

Diagnosis

Dan took his newly purchased, fresh-out-of-annual Warrior to a local mechanic on his home field and asked him to look the airplane over to find out the reason for its anemic climb rate and failure to make specified static rpm. The local mechanic reported the following findings:

- Compressions 50/58/62/64 with leakage past the valves. Lycoming specifies a minimum of 60. (The Texas mechanic who did the annual inspection recorded compressions of 71/73/68/74.)

- Borescope revealed all cylinders severely scored with obvious hot spots on the exhaust valves.

- Lifters bled down to reveal dry tappet clearance of about one-quarter inch on all cylinders, suggestive of a severely worn camshaft.

- Oil filter and suction screen contain a large quantity of ferrous metal (nearly half a teaspoon).

- Carburetor leaking fuel (dripping).

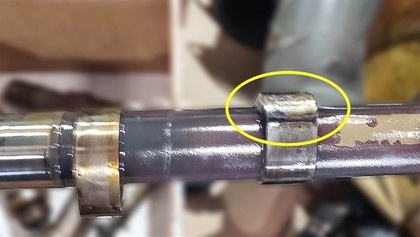

- Ignition harness has two cracked B-nuts, one that was completely broken in half.

- Trim cables severely worn and frayed.

- Brake hoses chafed through the protective metal braid.

“The airplane is grounded,” Dan reported, “and the engine needs to be torn down.”

The teardown confirmed what the metal in the filter and screen predicted: The engine internally was pretty much a train wreck. Several of the cam lobes were severely worn, the oil pump gears were damaged, and the bearings were contaminated.

Typically, the buyer is totally responsible for determining the acceptibility of the aircraft by means of an independent prebuy examination, and Dan didn’t have one performed.

“After looking over my notes and the logbooks, it appears that the Texas shop that performed the annual inspection had maintained this airplane exclusively for the past three and a half years and the shop owner was quite friendly with the previous owner. I do not see how the plane could have possibly been found airworthy during the annual inspection. These serious airworthiness issues should certainly have been caught during the annual and the airplane should never have been allowed to fly…. Is there some sort of liability on the shop or previous owner? Do I have any recourse?”

Any recourse?

I’m not an attorney, so I couldn’t offer Dan legal advice. However, typically in situations like the one Dan found himself in, the buyer does not have any legal recourse against the seller or the shop that performed the annual inspection.

Normally, the sale of a used aircraft is done on an “as-is” basis with no representation of airworthiness by the seller. (AOPA offers sample purchase agreements on its website.) Typically, the buyer is totally responsible for determining the acceptability of the aircraft by means of an independent prebuy examination, and Dan didn’t have one performed. Dan would have recourse against the seller only if the seller made a representation of airworthiness in the purchase/sale agreement he signed with the seller (and usually there is no such representation), or if Dan could show that the seller made some fraudulent misrepresentation of the aircraft on which Dan detrimentally relied.

It would be difficult for Dan to have legal recourse against the shop that performed the annual inspection, since the shop’s duty was strictly to the previous owner, not to Dan. The previous owner might have legal recourse against the shop, but only if the previous owner could show he was damaged by the shop’s apparent negligence. In this case it’s hard for me to see how the previous owner was damaged, since he was able to sell his airplane for very close to his asking price.

Just to make sure my advice to Dan was correct, I contacted my own aviation attorney (whom my company keeps on a retainer), told him Dan’s story, and asked him what he thought.

“Wow, poor guy!” replied my aviation attorney. “But you’re right, litigation would likely go nowhere for the reasons you cite—even assuming a lawyer would find the case to be financially worthwhile in the first place (which is doubtful). It could be exceedingly difficult to prove that the seller defrauded Dan. How could Dan prove that the seller knew of the problems with the aircraft? Even if he could, how could he show that the seller had a legal obligation to disclose what he knew? As for the mechanic who inspected the aircraft, he had no duty to Dan, only to the seller.”

At my suggestion, Dan contacted an AOPA Pilot Protection Services aviation attorney as well as his own personal lawyer. A “lawyer letter” alleging gross negligence was sent to the shop that performed the annual inspection. Fortunately, the shop was a large one that carried adequate insurance, so it turned the letter over to its insurance company.

The insurance adjuster made Dan a token $5,000 offer to settle the matter. Dan declined the offer, since it would hardly even be a down payment on what it will cost to make the Warrior airworthy. As I’m writing this, Dan’s attorney and the shop’s insurance adjuster are wrangling over a revised settlement amount. Based on what his lawyers are telling him, Dan seems hopeful but not confident of a satisfactory outcome.

Hard lesson

Dan learned the hard way something that I’ve been writing and speaking about for decades: An annual inspection furnished by the seller is no substitute for an independent prebuy examination conducted by the buyer.

My company manages hundreds of prebuys each year, and we have strict rules that we follow without exception. The prebuy examination must be performed by a shop or mechanic who has never seen the aircraft before, and who has no prior relationship with the seller (or with the seller’s broker if a broker is involved in the sale).

To ensure such independence, we require the seller to authorize the prospective buyer to perform a prebuy using any shop or mechanic of the buyer’s choice within one hour’s flying time of the aircraft’s home base. In almost every case, we insist on having the aircraft flown somewhere other than its home airport for the prebuy to guarantee that the examination is performed outside the seller’s or broker’s sphere of influence. Often this ferry flight doubles as a test flight to ensure that the airplane flies straight, performs to spec, and all systems and avionics are working properly.

If the seller or his broker will not agree to these terms, we invariably advise our client to pass on the aircraft and move on to another purchase candidate.