Aviation history from A to W

You can trace it through Ohio

Ohio Aviation History

Look to the eastern Midwest for that answer, and specifically to southwestern Ohio. In Dayton the Wright brothers conceived and built their early flying machines, and later validated and perfected the technology.

Printers who also published newspapers, the brothers began the Wright Cycle Exchange, a bicycle sales and repair business, on West Third Street in 1892. By 1895 it was the Wright Cycle Company, with its primary location at 22 South Williams Street. Wilbur and Orville became bicycle manufacturers in 1896 when they introduced their Van Cleve model; later in the year they began building a second model, the less expensive St. Clair. Only five Wright bicycles are known to survive today.

Both brothers were mechanically inclined, and Orville in his later years said a rubber-band-powered toy helicopter—a gift from their father, Milton, in 1878—ignited their interest in flight. After testing a kite design in 1899, they built and flew a series of manned gliders from 1900 to 1902. The Wrights based their wing warping on their observation of birds, and mounted the elevator in front—what we’d call a canard today. “One thing it sort of does is act as a parachute. As the airplane loses lift, it kicks up,” said National Park Service Ranger Ryan Qualls. The brothers realized that wing warping created drag, adding rudders to compensate. Today the South Williams location of Wright Cycle Company, where this development took place, is part of the Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park.

After achieving powered flight December 17, 1903, on the Outer Banks, the Wrights shifted their flying efforts to what became known as the Huffman Prairie Flying Field, northeast of Dayton and accessible via an electric interurban railway. It was on this then-remote, open prairie that the brothers truly mastered aircraft control—especially roll control, which the Wrights accomplished with wing warping, although ailerons became pretty much universal by the end of World War I. Today white flags mark each of the seven corners of the original field, and the brothers flew endless circles around its perimeter.

The ground of Huffman Prairie is as hallowed as Kill Devil Hill, and the two locations are inextricably linked—beneath the monument near the Huffman Prairie visitor center, a short drive from the field itself, is sand from Kill Devil Hill, and beneath the Wright Brothers National Memorial on Big Kill Devil Hill is soil from Huffman Prairie. The Wrights operated a flying school at the prairie from 1910 to 1916; among their students were Henry “Hap” Arnold, who commanded the U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II, and Canadian World War I ace H. Roy Brown, credited with shooting down the Red Baron.

As part of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, the site was closed to the public for decades. It became part of the Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park in 1992. Less than a quarter mile away you could encounter a closed road with a sign, “Shotgun firing area—do not enter.” The base Rod and Gun Club is nearby and Pylon Road is not far enough downrange, but roads to the west and then northeast provide an alternate access route. The detour is well worth it to see the site where flight truly came into its own.

The Wright Brothers Aviation Center, in Dayton’s Carillon Historical Park, features exhibits about the brothers’ life and work—and the 1905 Wright Flyer III, considered their first truly practical airplane, which Orville Wright helped to restore in the 1940s. The park’s founder, Edward Andrew Deeds, wanted a replica of the 1903 Flyer, but Orville talked him out of it. He realized the significance of the 1905 airplane.

Dayton had become an innovation hub and manufacturing center; around the turn of the century, more patents per capita were awarded in Dayton than any other U.S. city.

In 1910 the Wright Company opened the first airplane factory in the United States, on West Third Street in Dayton. The facility was acquired by General Motors in 1919, and was modified to build steering wheels; later, it produced auto parts as Delco and eventually Delphi. The plant closed in 2008 during Delphi’s bankruptcy. Recently added to the park, the factory is not yet open to the public.

The brothers planned to live out their years in a house on Hawthorne Hill, south of Dayton, but Wilbur died of typhoid May 30, 1912, before construction began. Orville lived to see astounding advances in aviation technology, and died in the house January 30, 1948. Both are buried in the Wright family plot at Woodland Cemetery and Arboretum in Dayton. Tours of Hawthorne Hill are offered twice a week through Carillon Historical Park.

It’s not surprising their inventing occurred in Dayton. It was the Silicon Valley of the 1890s. The city had become an innovation hub and manufacturing center; around the turn of the century, more patents per capita were awarded in Dayton than any other U.S. city. Charles F. Kettering, a National Cash Register engineer, developed the first electric cash register, and the electric starter for automobiles; he founded and later sold Dayton Engineering Laboratories Company—Delco. Weston Green introduced the popular Cheez-It snack crackers in Dayton. The Type A backpack parachute, controllable-pitch propeller, 100LL avgas, and aircraft ejection seat also were invented in Dayton.

After the Wrights

The Waco Historical Society in Troy, 20 miles north of Dayton, was founded in 1978. It honors the factory and employees of the Weaver Aircraft Company of Ohio, headquartered in Troy; the prolific early aircraft manufacturer became the Waco Aircraft Company in the late 1920s. There’s a comprehensive collection of Waco aircraft and the growing complex includes a new science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) center and extensive summer camp programs. There’s an event facility and a grass runway; Waco biplane flights are available.

Grimes Field in Urbana, Ohio, is a center of World War II-era preservation. The Champaign Aviation Museum is restoring its B–17 Flying Fortress, Champaign Lady , to operational status; the museum’s B–25 Mitchell, Champaign Gal , is a regular on the airshow circuit.

The Urbana airport is also home to the Grimes Flying Lab Foundation, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit dedicated to preserving the Grimes Flying Lab—a customized Beech Model 18 that was used by Warren G. Grimes and his Grimes Manufacturing Company to demonstrate different aircraft lights; it carries more than 75. Grimes has been called the father of the aircraft lighting industry.

Wapakoneta

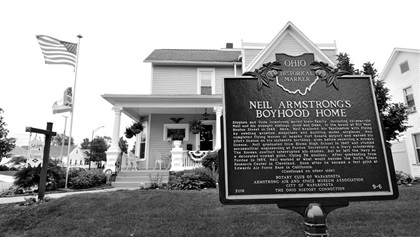

In 1944, 25 years before Neil Alden Armstrong would become the first man to step onto the surface of the moon, his family moved to Wapakoneta, population 9,867, about 60 miles north of Dayton. His parents purchased a home at 601 West Benton Street and Armstrong attended Blume High School, where he graduated in 1947 before studying aeronautical engineering at Purdue University. College was interrupted by duty as a Navy pilot and 78 combat missions in the Korean War. Armstrong completed his degree at Purdue in 1955, entered the NASA astronaut program in 1962, and commanded the Gemini VIII mission in 1966, before his selection to command the Apollo 11 mission.

In 1944, 25 years before Neil Alden Armstrong would become the first man to step onto the surface of the moon, his family moved to Wapakoneta, population 9,867, about 60 miles north of Dayton. His parents purchased a home at 601 West Benton Street and Armstrong attended Blume High School, where he graduated in 1947 before studying aeronautical engineering at Purdue University. College was interrupted by duty as a Navy pilot and 78 combat missions in the Korean War. Armstrong completed his degree at Purdue in 1955, entered the NASA astronaut program in 1962, and commanded the Gemini VIII mission in 1966, before his selection to command the Apollo 11 mission.

The Armstrong Air and Space Museum opened in Wapakoneta during 1972—only three years after the first lunar landing—in a unique structure meant to resemble a future moon base. Exhibits include spacesuits, moon rocks, and the Aeronca Champ in which Armstrong learned to fly at the long-closed Port Koneta Airport, which was located north of Wapakoneta.

While the home where Armstrong lived is now a private residence, it can be seen from the sidewalk—look for the historic marker. Karen Tullis bought the house in December 1988, not realizing at the time it had been the Armstrong family’s. A teacher she worked with told her that Armstrong had lived there. “I said, ‘Yeah, sure, Barb.’” But the coworker told her, “Neil and I went to the prom, but we had to walk. He could fly an airplane but he couldn’t drive a car.”

While the home where Armstrong lived is now a private residence, it can be seen from the sidewalk—look for the historic marker. Karen Tullis bought the house in December 1988, not realizing at the time it had been the Armstrong family’s. A teacher she worked with told her that Armstrong had lived there. “I said, ‘Yeah, sure, Barb.’” But the coworker told her, “Neil and I went to the prom, but we had to walk. He could fly an airplane but he couldn’t drive a car.”

Tullis keeps Armstrong and space memorabilia in the bedroom the astronaut and his brother shared at the top of the stairs. “It’s been a pleasure to have this house,” she said. “Not just because Neil lived here, but to help preserve history. My ultimate goal is to preserve it much as it was like when they were here.”

If you want to enjoy Armstrong’s favorite dessert while visiting, it’s black raspberry chocolate chip ice cream from Graeter’s—a regional ice cream company based in Cincinnati—with brownies.

Email [email protected]

The contributions of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base to the development of military aviation date almost from the time of Wilber and Orville Wright. Today it’s home to the Air Force Materiel Command, Air Force Life Cycle Management Center, Air Force Research Laboratory, and the National Air and Space Intelligence Center, among other units and functions.

The contributions of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base to the development of military aviation date almost from the time of Wilber and Orville Wright. Today it’s home to the Air Force Materiel Command, Air Force Life Cycle Management Center, Air Force Research Laboratory, and the National Air and Space Intelligence Center, among other units and functions.  A former National Park Service ranger in the Dayton area, Simmons said this is his dream job. Although it’s not required, he has an airframe and powerplant certificate—half of the 12 restoration specialists do. “You’re not working on flying airplanes, but the techniques are very valuable,” he said. “It’s all about attention to detail.” —MC

A former National Park Service ranger in the Dayton area, Simmons said this is his dream job. Although it’s not required, he has an airframe and powerplant certificate—half of the 12 restoration specialists do. “You’re not working on flying airplanes, but the techniques are very valuable,” he said. “It’s all about attention to detail.” —MC