Proficiency: Real deal

Staying IFR proficient without a ‘real’ airplane

Of the skills I maintain for the various kinds of flying I do, my instrument skills atrophy most easily, so fulfilling the FAA regulations might guarantee currency but often not proficiency. Thus my personal minimums involve logging at least three approaches in my airplane within the past two months, but this can be tough to do. My home airport has no published instrument approach procedures, so I only depart on an instrument proficiency flight if I’m virtually certain to be able to return that day, and that means visual conditions and a safety pilot. Carving out a time in my hectic schedule that aligns with a friend’s availability often requires surgical precision.

Of the skills I maintain for the various kinds of flying I do, my instrument skills atrophy most easily, so fulfilling the FAA regulations might guarantee currency but often not proficiency. Thus my personal minimums involve logging at least three approaches in my airplane within the past two months, but this can be tough to do. My home airport has no published instrument approach procedures, so I only depart on an instrument proficiency flight if I’m virtually certain to be able to return that day, and that means visual conditions and a safety pilot. Carving out a time in my hectic schedule that aligns with a friend’s availability often requires surgical precision.

Two years ago, the FAA made it easier and less expensive for pilots to maintain instrument currency. In particular, the new rule allows flights completed in an aviation training device (ATD) to count toward instrument currency requirements. And the fact that an instructor no longer needs to be present sweetens the deal even more. Still, I continued to call on my friends to serve as safety pilots because I considered experience in my airplane superior to that in an ATD. To be honest, it probably had more to do with the fact that I’m just bad with ATDs.

Years ago when getting checked out in a Piper Seminole, my instructor Greg suggested we start in the ATD as an efficient and cost-effective way to acquaint me with the avionics, and I gladly agreed. He fired it up and put me on the very runway from which we would soon depart in the Seminole. It felt a bit awkward as I adapted my scan to this unfamiliar panel and received no force feedback from my control inputs, like I would get in the real airplane. Soon the screens went white as we entered the clouds and I set up for a sequence of instrument approaches back to the airport. Greg didn’t say anything beyond assigning me tasks, so I knew I was handling them well and my confidence grew. Now it was time to head to the real airplane. We climbed to altitude, leveled off, and began performance maneuvers like steep turns, stalls, and single-engine operations. With what seemed like a gasp of relief, Greg broke his silence by blurting, “Oh, so you can fly.”

We all have some Achilles heel when it comes to aviation, and it turns out that mine just doesn’t involve an actual airplane.That day I concluded that ATDs just weren’t my thing. I made a pact with myself to stick with flying real airplanes, and I did just that for more than 15 years. But such avoidance isn’t healthful, and my aversion to them only grew with time. As a flight instructor, I specialize in helping pilots who fear stalls or loss-of-control events fly their airplanes more safely and with greater confidence. We all have some Achilles heel when it comes to aviation, and it turns out that mine just doesn’t involve an actual airplane. “Find the situation that scares you the most and train for it in a safe, controlled environment” is the advice I offer that at the end of every safety presentation I give for the FAA. Despite needing a dose of this myself, I stuck to my usual instrument currency program.

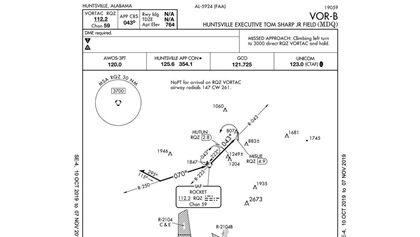

What finally convinced me that I needed to give ATDs another try happened while administering a recent instrument rating practical exam. The Huntsville Executive Airport (MDQ) is close by and offers ILS, localizer, VOR, and RNAV approaches so we use it regularly. In particular, the VOR-B approach procedure is an interesting one (see the portion of the instrument approach procedure chart on page 98). The course to the VOR is 70 degrees but changes to one of 43 degrees for the final approach segment. I suspect this dogleg keeps Huntsville Executive traffic away from aircraft bound for the Huntsville International Airport and the nearby restricted areas. I’ve seen some creative ways of flying the approach and this candidate flew only a 43-degree course, essentially removing the dogleg from the approach. Later when I asked what went wrong, he explained, “Well, I’ve never seen an approach like that before and it threw me for a loop.” I suggested that he get more practice away from his home airport so he’d encounter more variety. Then I realized that my own proficiency regimen suffered from the very same homogeneity as his, so I had yet another opportunity to take my own advice.

I called and found an ATD at the Smyrna Airport in Tennessee, and scheduling was easy. When I walked into the flight school, instructor Alex Harcrow was running the Precision Flight Controls CRX ATD for his student Faith Berg. He graciously demonstrated how the program worked while Berg skillfully navigated the virtual aircraft through several departures, approaches, and landings, even applying heavy pressure to the brakes to avoid the deer that ran in front of her airplane. As they were concentrating on emergency situations, Berg handled smoke in the cockpit according to her checklist and managed a landing following a bird strike. I learned several additional features that make ATDs terrific training tools:

No peeking. Let’s face it—view-limiting devices don’t replicate instrument conditions. Even the best ones can’t offer a full view of the panel without allowing a peek outside now and then. An occasional glance at the horizon can help the pilot maintain orientation and make a poor scan seem effective. The ATD encourages developing and maintaining a good one.

Realistic emergencies. The Instrument Rating Airmen Certification Standards requires that examiners fail instruments during one of the nonprecision approaches. If the aircraft is equipped with a vacuum system, this might mean putting sticky notes over the attitude and heading indicators, but the aircraft doesn’t betray the emergency with such fanfare. In an actual vacuum system failure, the attitude indicator begins to lean slowly so the pilot can commence a turn or even enter a spiral by following it. The ATD gyro instruments faithfully reproduce the same symptoms and promote including the vacuum gauge as a regular part of the instrument scan.

Impact of weather. Pressure setting, temperature, wind, and precipitation type are just a few of the settings that can be programmed for a flight in the ATD. Before one planned takeoff Berg determined, based on the obstacle departure procedure and the conditions Harcrow set, that the aircraft performance would be insufficient to make the required climb profile. Not every flight should be attempted and sometimes we need to shut down and wait for better conditions. I was pleased to see Harcrow present such a situation in training.

When they finished with their session, it was my turn to give it a try. I flew the ILS 22L into John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK) and followed it with the RNAV (GPS)-A to the Mariposa-Yosemite Airport (MPI), where my father took flying lessons in the 1950s. My tour of the country finished with a LOC/DME approach to Aspen-Pitkin County Airport (ASE). While I can’t say I’ll be spending all my free time flying ATDs, it wasn’t so bad after all, and I now recognize them as an effective—and even necessary—complement to flying my own airplane with a safety pilot. On a cold day with clouds too low to fly, I extended my currency, improved my instrument scan, and saved some money to boot.

Some say a great flight is one after which the airplane can be reused. By all appearances, I left the ATD in that condition so I’m chalking the session up as a rousing success.

Catherine Cavagnaro is an aerobatics instructor (aceaerobaticschool.com) and professor of mathematics at Sewanee: The University of the South.