Fly the roof, skip the ladder

Insurance inspections offer opportunity for remote pilots

Natural disasters often leave insurance adjusters scrambling to document the damage, and that can present an opportunity for remote pilots with the right skills, software, and connections.

Insurance claim payments for broken or missing roofs usually depend on insurance inspections, and the demand for inspectors can be overwhelming in the wake of a major event such as a hurricane.

“I was getting on five or six roofs a week, some of them complex two-or three-story structures with steep roofs,” Powers said. Gaining vantage (and footing) on some of those precarious slopes for damage inspection sometimes involved calling for larger ladders and rigging ropes to prevent falling. “I thought there had to be a better way to inspect those,” Powers said recently in a phone interview while en route to a job several hours away.

As if that notion needed reinforcing, while inspecting an older home, a plastic rain gutter that his ladder was leaning against cracked under his weight. Powers and his ladder tumbled, damaging a window along the way. Making the case for finding a “better way” became as easy as, well, falling off a ladder.

Powers was aware of drones, and thought they were “cool,” but until this point he hadn’t seen the justification for the expense.

Not subscribing to the “walk before you run” philosophy, Powers sprang for a DJI Inspire 1 Pro, obtained his Part 107 certificate, and developed a plan for inspecting damage from the safety of the ground. The success he has shown over the last three-and-a-half years convinced his company to purchase additional drones for use by other agents. More staff adjusters are in the process of preparing for the Part 107 test. When those adjusters earn remote pilot certificates, Powers will ensure that a standard approach to documenting damage is followed, including adhering to a flight plan he developed to deliver report consistency.

The ultimate justification is a familiar refrain where unmanned aircraft are concerned: safety and efficiency. Referring to the former, Powers says, “Metal roofs, if they have any dust on them, can be almost as slick as ice.” He adds that by flying a metal roof inspection at the right time of day, he can see the screws backing out of a metal roof from their shadows.

While the Inspire 1 Pro proved to be capable, Powers has since moved on to Mavic 2 Pros and Phantom 4 Pros. He cites their lighter weight and size, capable camera sensors, and good battery life. Smaller and lighter matters when you’re also lugging other equipment along, usually alone. Powers says the camera chips in his drones are more than adequate for insurance needs.

Powers has become a fan of the DJI Smart Controller, as he says it tends to fare better in heat, and can offer a brighter presentation. Its integrated simplicity also avoids potential fussing he or other agents would have with cables and iPads.

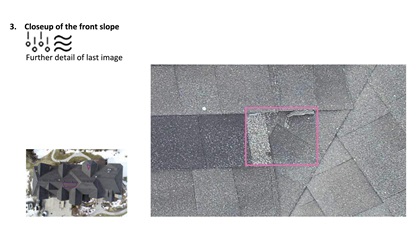

Inspection photos are typically taken five to seven feet above the roof. There is no need for the additional image data available from RAW files, and missions are shot on auto exposure to ensure that any questions about image manipulation are put to rest. Since some insurance claims involve litigation, it is important to leave all image metadata intact and to avoid any of the “toning” that many drone pilots apply to their edits with imaging applications.

According to Powers, when calamity strikes and large-scale damage results, there is plenty of work to go around. Referring to an April storm, he recalls, “I had 30 structures assigned to me and I don’t have enough hours in the day to do that.”

That’s when it’s advantageous for other Part 107 certificated pilots, depending on experience level, to be acquainted with area insurance adjusters.

“If you have a big event like a big windstorm or hailstorm that hits hundreds or thousands of homes and structures in an area, the insurance companies are scrambling and they're going to need people to help out and look at those. If you are known to the companies, the adjuster is able to reach out to you and assign roofs and structures to inspect.”

Powers suggests drone pilots connect with them, perhaps join adjuster associations as an ancillary member, and do presentations of UAS work. Says Powers, “Get in front of them and show them what you can do. Emphasize how you can help them become efficient, how you can take these safety factors out of the equation.” Powers suggests that a webinar on the utility of drones can be an effective, wide net to cast.

Powers reminds drone operators seeking this kind of work that without an adjuster’s license, their job is only to take and deliver well-organized photos, not interpret the data. That falls to others to assess as part of working a claim.

A typical residential drone inspection for Powers might involve 50 to 60 photos, taken according to a flight plan that begins with an overall view, shot at 45 degrees, and ideally showing the full home and address. Then subsequent photos are taken in a clockwise pattern working around the roof (or roofs). With this well-honed technique under his belt, Powers can knock out a flight in 15 minutes and often get two locations covered with one drone battery.

While drones can capture the bulk of the damage a claim might involve, they aren’t for every roof. Powers notes that some roofs can be problematic. TPO (rubber to most of us) roofs are often white, and “it’s hard to see damage on those just because of how much light they reflect.” Metal roofs can cause interference, requiring good Atti (manual, no GPS) mode skills. In short, while Powers says about 50 percent of his roof climbing has become drone-flying, there are plenty of situations that still need to be approached one rung at a time, up close.

Insurance drone flights, while not sexy, still sometimes draw curious and confrontational onlookers. Powers routinely sets up a dedicated video camera on a tripod to record what he is doing. This eliminates any questions about how and from where he is doing his job, and also creates a video record of any confrontations over spying or trespassing. Powers also carries a binder of drone regulations, which, coupled with a calm explanation of his job, defuses most situations.

Powers is willing to assist pilots who want to learn more about getting a piece of the drone inspection business. He can be reached through his site, Sky High Aerial Imaging, or by email. He and other small unmanned aircraft operators share opportunities and information at the Commercial sUAS Remote Pilots Facebook page.