Flight Lesson: Another 10 minutes

Carbon monoxide poisoning happens quickly

By Joe Standley

I went up with my instrument student, Ken, in his Piper Dakota to do some hood work. The winds were strong and gusty, and it was turbulent. Every now and then a strong gust of wind would push exhaust fumes into the airplane. A carbon monoxide detector was on the instrument panel in plain view.

On the way to the practice area I noticed a breeze in the airplane that I hadn’t noticed a few days earlier. The door, baggage door, and the vents all were closed.

About 20 miles west of the airport we began drills, including turns and varying aircraft configurations. Students often get dizzy during this lesson, and turbulence tends to make it worse. Ken mentioned that he was a little dizzy and asked if he could take a break.

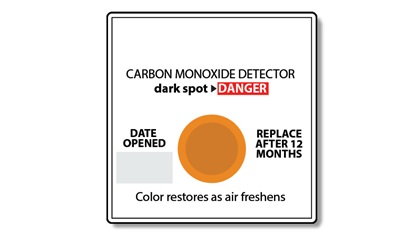

Part of me wondered if it might be carbon monoxide, even though the detector indicated everything was good. I opened the window and the overhead vent and said we should head back. I felt a little dizzy, too.

On the way back to the airport, I asked Ken if he was OK to land. He said he was still feeling off and was struggling to find the runway. The carbon monoxide detector, which was new, showed no change.

I landed the airplane, and as I taxied off the runway, I felt more dizziness. I told Ken I thought we may have carbon monoxide poisoning. Ken taxied back to his hangar, where we shut down. He stumbled getting off the wing. He started to take the tow bar out and I told him to stay put and take deep breaths.

We hooked up the towbar. Ken then started wobbling and I caught him and kept him from falling. I laid him on his back and his body started to lightly shake.

One of the airport staff was in the hangar next to us. I asked him to call an ambulance. When it arrived, I asked to be checked, too. I noticed my feet were numb from the ankles down and my hands and lips felt the same. My hands were shaking. A headache soon followed, which lasted all night.

The paramedics said that with anything over 12 percent carbon monoxide, it is recommended that you go into an oxygen chamber. Ken’s carbon monoxide level was at 26 percent and mine was at 19 percent. Neither of us wanted to sit in a tent for 24 hours. They said we would still be fine, but it might take a day or two to get back to normal levels. Ken later told me that he was struggling to understand the instruments on the way back. He also didn’t remember taxiing back or shutting down.

This wasn’t easy to recognize, especially with a brand-new carbon monoxide detector saying we were safe. Spend $160 on a portable electronic detector; they are more sensitive and accurate than the $10 one. If you smell fumes and you are dizzy, get back to the airport. It took 15 minutes from the time the dizziness started to the point where one of us couldn’t function. Another 10 minutes, and we both would have been unconscious on our way back to the airport.

Ken was going to travel in that airplane with his family that weekend. The effects we experienced could have been much worse in a small child, and no one would have noticed since kids usually fall asleep while traveling. Someone was looking out for us and his family.

Joe Standley is a flight school owner and 27-year pilot from Lake in the Hills, Illinois.

“Part of me wondered if it might be carbon monoxide, even though there wasn’t a strong smell of exhaust and the detector indicated everything was good.”

“Part of me wondered if it might be carbon monoxide, even though there wasn’t a strong smell of exhaust and the detector indicated everything was good.”