Industry News

‘Pong with planes’

Microsoft reboots its flight simulation classic

By Jim Moore

For many pilots, the words Microsoft Flight Simulator take us back to the day we first fell in love with flight, however “fake” the flying may have been (or how young we were at the time). Clunky computers with cathode ray tubes and keyboard controls, nary a mouse in sight—much less a yoke or pedals—lit the spark for a generation of pilots who went on to become airline captains or AOPA editors. Decades later, what was clunky and cute is reborn as a sleek, stunningly realistic desktop simulator that has arrived just in time to help pilots emerging from pandemic-induced lockdowns sharpen their skills in perfect safety. First released in November 1982, Microsoft Flight Simulator version 1.0 was written for MS-DOS, and sold on floppy disks that today’s teens might not recognize; there was no Facebook or Twitter on which to buzz about it back then.

The realism of that first release leaned heavily on the player’s imagination. AOPA Senior Director of Communications Eric Blinderman recalled that the 1980s iteration was “like playing Pong with planes.” Over time Microsoft’s game studio developed Bruce Artwick’s original code into a more realistic, robust training tool.

By the turn of the millennium, the original version was much improved. Ian J. Twombly, a senior content producer for AOPA, says he “taught myself VOR navigation on Microsoft Flight Sim” in 1999: “I had just experienced a horrible lesson on VOR navigation with my instructor. We were arguing how to intercept a radial toward the station, and I was not getting it. Reading the textbooks hadn’t done anything to advance my knowledge. So, I got on my Microsoft Flight Sim from the default location of Meigs Field, spent about 30 minutes teaching myself intercepts, and never looked back.”

Years of refinement had turned “Pong with planes” into a legitimate aviation tool, useful for practicing instrument procedures and even, at least to some degree, stick-and-rudder work, albeit without the motion and control feedback found in more expensive simulation. AOPA published custom scenarios for Microsoft Flight Simulator 2000, a set of preprogrammed plug-ins that facilitated virtual instrument approaches to AOPA’s real-life home, Frederick Municipal Airport in Frederick, Maryland.

As the software became more advanced, online flight simulation communities coalesced to share the experience, and to expand existing code with custom creations, including scenery and aircraft. Many contributors were aviation enthusiasts who had never flown an actual airplane, although certificated pilots also got into the act–including Connecticut pilot Scott Gentile, who founded A2A Simulations to produce realistic digital aircraft models for various flight simulation platforms. Slowly, digital modeling and computer simulation worked its way into pilot training, giving us the basic and advanced aviation training devices found in flight schools around the country.

Flight simulation became a shared experience, thanks to online communities such as AVSIM that hosted forums to share software plug-ins, offer troubleshooting advice, and organize simulated flights. By 2009, competition from other flight simulation engines had taken the realism to new levels and left Microsoft behind. The company shuttered its Aces Game Studio that year, but Microsoft Flight Simulator was licensed to Dovetail Games, which released a Steam edition of Flight Simulator X. (For those of you of the Intel 8088 generation, Steam is an online gaming protocol that allows multiple players to remotely access a game hosted on a single computer.) There was also Microsoft Flight, a free download released in 2012 that was more like an arcade game than a simulator, though it has its fans (and its own forum on AVSIM).

For the 2020 release, Microsoft turned to French software development studio Asobo, and essentially handed the company a clean sheet of paper and the keys to Microsoft’s Bing Maps database. Microsoft Flight Simulator (2020) seems unlikely to be a one-off, but the first step in Microsoft’s bid to return to dominance in home computer flight simulation.

It looks gorgeous. The fine details of lighting and shading are captured in still images released by the company to support preorders and watching the videos of recorded in-game action stirs a familiar longing in the heart of this pilot, at least. The airplanes appear to move like airplanes do, carving through a virtual world where weather and wind can be customized to an unprecedented degree. Early reviewers have raved about the release, which is available (for computers running Microsoft Windows) online, starting at $59.99 for the basic software package, which includes 20 aircraft and 30 “hand-crafted” airports, simulated in more detail than the other 37,000 airports in the game. The Deluxe Edition ($89.99) adds five aircraft and five highly detailed airports, and the Premium Deluxe package ($119.99) adds 10 more aircraft and 10 airports with the full digital treatment. That should tide us over for a while.

ASI News

Under pressure

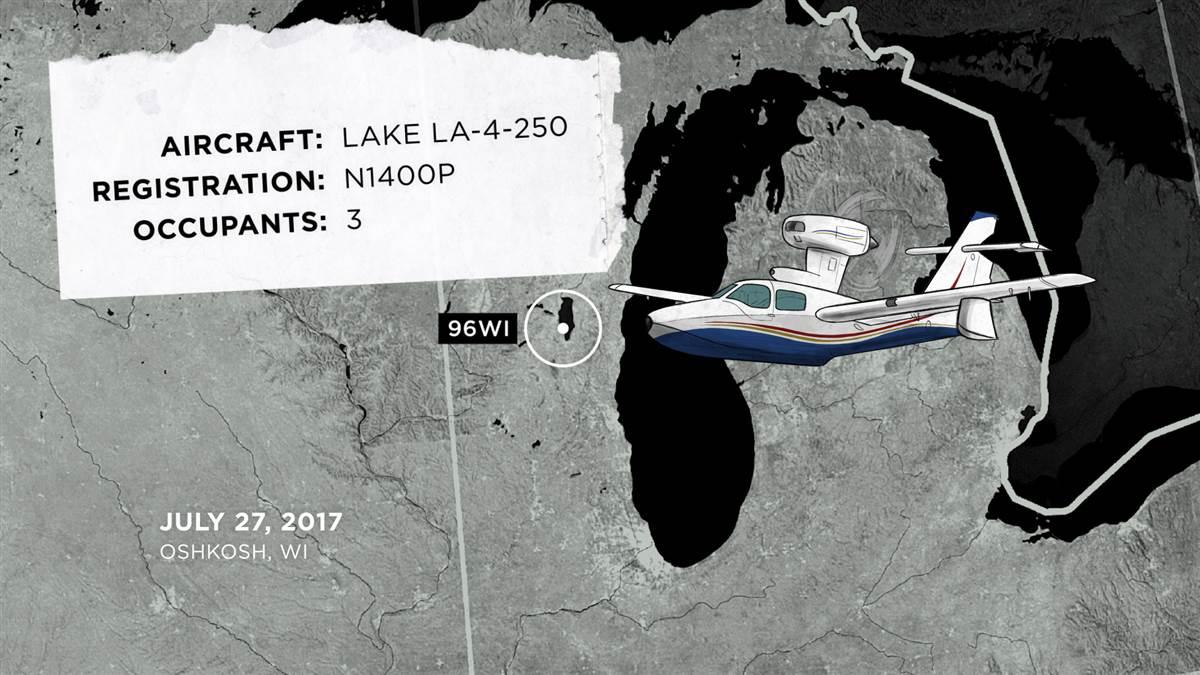

Accident Case Study: Lake Renegade

By Alicia Herron

Whether during primary flight training or after the checkride, sooner or later a pilot is likely to feel time-based external pressure to complete a flight as planned. Maybe we need to get our rental airplane back for the next student’s lesson, make it to a family dinner on time, or land before sunset because of currency or proficiency. It could be a combination of all three. No matter the specifics, as pressure mounts and the clock ticks, it can be hard to take a step back, reassess a situation, and spot potential hazards—even for highly experienced aviators.

On July 27, 2017, a Lake Renegade amphibious aircraft arrived at the Oshkosh, Wisconsin, seaplane base for an afternoon during AirVenture week. After a brief stay, the 33,000-hour airline transport pilot became anxious to load his two passengers, including a 2,400-hour CFI in the right seat, and depart—the trio didn’t have accommodations booked for an overnight stay. Lake Winnebago was choppy, and as the pilot attempted to get underway, the seaplane base staff repeatedly warned the pilot of the danger of taking off on high waves. The pilot ultimately chose to depart despite the poor conditions and advice to stay put.

Watch the AOPA Air Safety Institute’s re-creation of the accident, where we follow the events of the day and seek to understand and learn from the circumstances that led to this ill-fated takeoff.

airsafetyinstitute.org/acs/lakerenegade

VFR into IMC: What’s the problem?

One reason flying VFR into instrument meteorological conditions can be hazardous to pilots is because of the possibility for spatial disorientation. Spatial disorientation is the mistaken perception of one’s position and motion relative to the Earth. That means your body will tell you one thing (“we’re turning”) and the instruments will tell you another (“we’re level”). Since we humans rely on vision for 90 percent of our point of reference information, any condition that deprives a pilot of natural visual references—like flying in clouds—can rapidly cause spatial disorientation. Pilots can avoid relying on their “feelings” to guide them in flight by learning to fly by reference to their instruments. If you’ve never experienced spatial disorientation before, ask your CFI to put you under the hood and try to disorient you (in visual conditions, of course). Learn more about spatial disorientation: airsafetyinstitute.org/spotlight/spatialdisorientation

VFR into IMC continues to be a leading cause of fatal accidents in general aviation. In this episode, pilot Robert Clark recounts the story of flying his Dyke Delta airplane through unexpected instrument conditions during an electrical failure at night, and what he did to stay alive.

VFR into IMC continues to be a leading cause of fatal accidents in general aviation. In this episode, pilot Robert Clark recounts the story of flying his Dyke Delta airplane through unexpected instrument conditions during an electrical failure at night, and what he did to stay alive.