The inside story

For many customers, the cabin comes first

Photography by AOPA staff and courtesy manufacturers

It depends on whom you ask, of course. But when it comes to a buying decision, the interior often sways the deal. Passenger satisfaction is always a prime concern, and let’s face it, in the turbine world the passengers frequently are the ones writing the check.

Both art and science are involved in aircraft interior design. Often there are tradeoffs. From the start, the designer is faced with a space that’s rigid in dimension. By necessity, the cabin is a long tube, so creating a sense of open space is a challenge. Regulations dictate that carpets, seats, and other elements be made of fire-resistant materials. Crashworthiness rules mean seat belts and shoulder harnesses, but they may also mean air bags if there are side-facing divans, lest heads smack into a bulkhead during a sudden deceleration. It also means having clear aisles for emergency evacuations. Pressurized cabins dictate the design, size, and location of windows, doors, and emergency exits, as well as the need to accommodate supplemental oxygen systems, and storage for a raft and life vests.

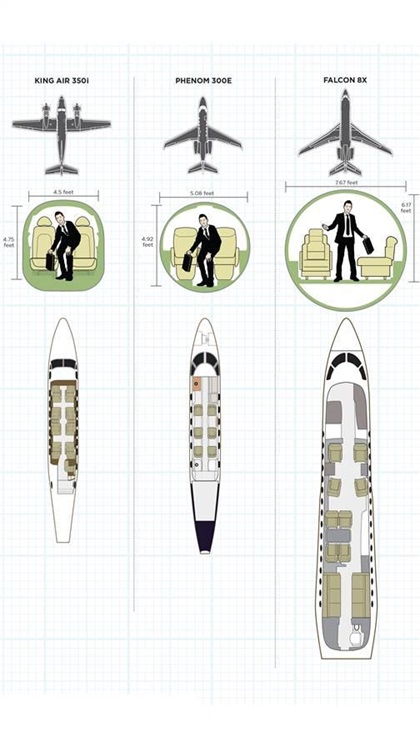

Turbine Aircraft interiors

Even floors bring compromises. Many smaller turbine airplanes have dropped aisles—a sort of trench that runs fore and aft. Space in fuselage cross-sections is at a premium, so hydraulic and other systems components are crammed into the belly of the airplane, encroaching on the cabin. To make room, the edges of the cabin floor are raised. So, to create ergonomically valuable headroom, the aisle is dropped. The flat floors featured in big-cabin, long-range jets are best because passengers are free to move about—there’s no trench to navigate. The worst floors? They were in early bizjets such as the Sabreliner, which had wing spars running across the cabin floor. You had to step over them to enter the cabin.

Even floors bring compromises. Many smaller turbine airplanes have dropped aisles—a sort of trench that runs fore and aft. Space in fuselage cross-sections is at a premium, so hydraulic and other systems components are crammed into the belly of the airplane, encroaching on the cabin. To make room, the edges of the cabin floor are raised. So, to create ergonomically valuable headroom, the aisle is dropped. The flat floors featured in big-cabin, long-range jets are best because passengers are free to move about—there’s no trench to navigate. The worst floors? They were in early bizjets such as the Sabreliner, which had wing spars running across the cabin floor. You had to step over them to enter the cabin.

But big cabin or small, space is always limited. Seats that track and swivel can move away from the sidewall, giving the feel of more room to passengers. In big jets, splitting the cabin into different zones is another way to reduce the perception of confined space. And big jet or small, ergonomics and dimensioning are king—and a key to comfort. Don’t think so? In some cabins cupholders are placed right where your elbow rests. If the seat angle is too shallow, or the elbow-rest or thigh-length measurements are too big or small, the passenger will know it. For example, a shallow seat angle makes the body want to slide forward.

Sometimes even the smallest details can invoke a subliminal appreciation. You may not understand quality interior design, but you know it when you see it.Then there’s the overarching matter of style. Trends come and go, so older cabins show off the fabric seats, auburn hues, and garish patterns of the 1960s and ’70s. In the past the fashion was often to make cabins resemble home environments, right down to window curtains and table lamps. Today’s cleaner, brighter, more open design ethic is largely informed by high-end automobile design, the kind pioneered by BMW DesignWorks. Cloth seats have largely disappeared; natural materials such as leather, and ecologically friendly materials, now prevail.

Sometimes even the smallest details can invoke a subliminal appreciation of quality design. The curve of a table, the layering of wood and metal, the precise execution of a hinge, an embossed leather compartment, or a seat’s special texture and stitching—all can appeal to passengers, without their even knowing it.

Of course, any discussion of big-iron interiors would be remiss if it didn’t mention those over-the-top treatments we love to judge. You know, the ones with gold-plated sinks and toilets, sunken living rooms, and bedrooms with showers. They’re the province of the wealthiest owners of the largest jets. They want to make a statement, and do they ever. Whether it’s a luxury penthouse, a lodge in the mountains, or cigar/martini-bar mancave, interior completion centers have seen it all.

Aircraft interior design is a highly specialized field, right up there with automotive and yacht design. In many ways it’s one of the more challenging and expressive of the design fields, and perhaps the highest calling for those with the knack for merging form, style, and function with human factors.

Email [email protected]