Italian style/American muscle

These magnificent seabirds came to race

The pilots of these magnificent flying boats aren’t here to gawk, however. They’ve come to race, and that means putting their prized vintage air yachts to a strenuous series of head-to-head performance contests, including a wide-open drag race.

“Ready to go to max continuous [power]?” John Mohr, pilot and owner of the Piaggio P.136 Gull (see “’Way Ahead of its Time,” May 2021 AOPA Pilot), asks rival Brian Van Wagnen, pilot, owner, and restorer of the Grumman G–44 Widgeon.

These two retired airline pilots are devoted, lifelong seaplane fliers, good friends, and stalwart advocates for their aircraft types. But on this clear and calm late afternoon, they’re also competitors.

“I’m ready,” Van Wagnen answers. “Go ahead and push it up.”

Side by side at an altitude of 3,500 feet over the forested Minnesota/Wisconsin border, the pilots advance throttles and propeller levers so that all four of their geared, six-cylinder, Lycoming engines are roaring at 3,000 rpm. Their finish line is a Beechcraft Bonanza A36 serving as the photo ship about two miles ahead.

“The race is on,” says AOPA Senior Photographer Chris Rose, perched with his cameras beside the Bonanza’s open cargo door. “I’m watching an absolutely unbelievable sight.”

Big differences

This Gull and Widgeon have lots in common. They’re both twin-engine, Lycoming-powered, five-seat, metal flying boats with retractable, tailwheel landing gear, and high wings to protect their constant-speed, three-blade, Hartzell propellers from water spray. Both designs flew for the first time in the 1940s, and they were meant for the civilian market—although military operators took a liking to them, too.

Both designs were originally made with smaller engines that proved unsatisfactory (a Franklin in the Gull and a Ranger in the Widgeon). Both seaplanes in this flight are equipped with GO-480 engines rated at 295 horsepower each.

But the airplanes have major differences, too.

The Gull has pusher props that are reversible. Gull pilots can use reverse to shorten landing rollout and back up on land or water. And the Gull has a retractable water rudder. Widgeon pilots are limited to differential thrust for water steering, and they can’t back up or go straight ahead on one engine.

The Widgeon has retractable wing floats, while the Gull’s are always down.

Widgeon passengers and cargo ride behind the wings in the main fuselage. Gull passengers sit on a bench seat that resembles an overstuffed sofa just aft of the pilots, and there’s a separate cargo compartment (300-pound capacity) behind the wings.

The Gull has big doors on both sides of the cockpit. The Widgeon has a single door on the left side of the fuselage. For docking, anchoring, or emergency egress, the Widgeon has a nose hatch that crew members crawl forward to reach. The Gull has a fold-out windshield on the right side of the cockpit, and a crewmember can stand up or step forward to reach a cleat on the bow.

In terms of size, the Gull is much bigger both in external dimensions and weight. The Gull’s empty weight is a hefty 1,400 pounds more than the Widgeon, and the Gull is taller, wider, and has a broader wingspan.

The two airplanes also have distinctive and contrasting appearances.

The Gull’s V-shaped wings are impossibly thick at the roots and they contain massive amounts of dihedral—lots inboard of the engines and some outboard. Its round, over-wing air intakes resemble the gaping mouths of giant koi fish. Yet in the air and on the water, the airplane is surprisingly sleek, modernistic, and aesthetically appealing.

“Italian designers have always had a gift for lines, symmetry, and style,” Mohr said. “Ferrari, Bugatti, Piaggio. Style is an essential part of their DNA, and their products are just imbued with it.”

Twice wrecked

The Grumman Widgeon is the smallest of the multiengine flying boats produced by the legendary “iron works” in Bethpage, New York, during its heyday. The Widgeon was mini-me to its predecessor, the iconic Grumman Goose. The Widgeon was meant for the civilian market but quickly got swallowed up by world events.

After Pearl Harbor, most Widgeons were pressed into military service for the duration of World War II where some were armed with depth charges and searched for (and occasionally found, attacked, and even sank) German U-boats.

This one, serial number 1240, was the first exported to Canada. It worked for a series of mining companies before being badly damaged in a glassy water landing in 1948. According to an anthology of Grumman aircraft, its left float hit an obstacle, and that caused the right float to dig into the water. “The left float was torn off and the aircraft capsized. Towed to shore while inverted, dismantled, and trucked to Ontario for repair.”

Years later, the resilient airplane was sold to the fish and game department in Quebec. Then it went through a series of government and airline owners before being torn up again in 1966. On a flight from Fort Nelson to Prince George, British Columbia, the left engine lost power and the pilot attempted an emergency landing on an airstrip beside the Alaska Highway.

“The right float touched first, then the left main landing gear struck a pile of debris and the left wing hit trees,” according to the Grumman compilation. The wreckage was sold to a salvage firm in Tecumseh, Michigan, in 1967. The aircraft was returned to airworthy condition during the next two years, then changed hands a couple more times before Brian and wife Karen Van Wagnen bought it in March 2004.

Van Wagnen first flew the airplane decades earlier, however, in 1970, at age 18, and he helped maintain and upgrade it long before buying it. The couple converted their airplane to a Super Widgeon with Lycoming GO-480 engines and increased its gross weight to 5,500 pounds.

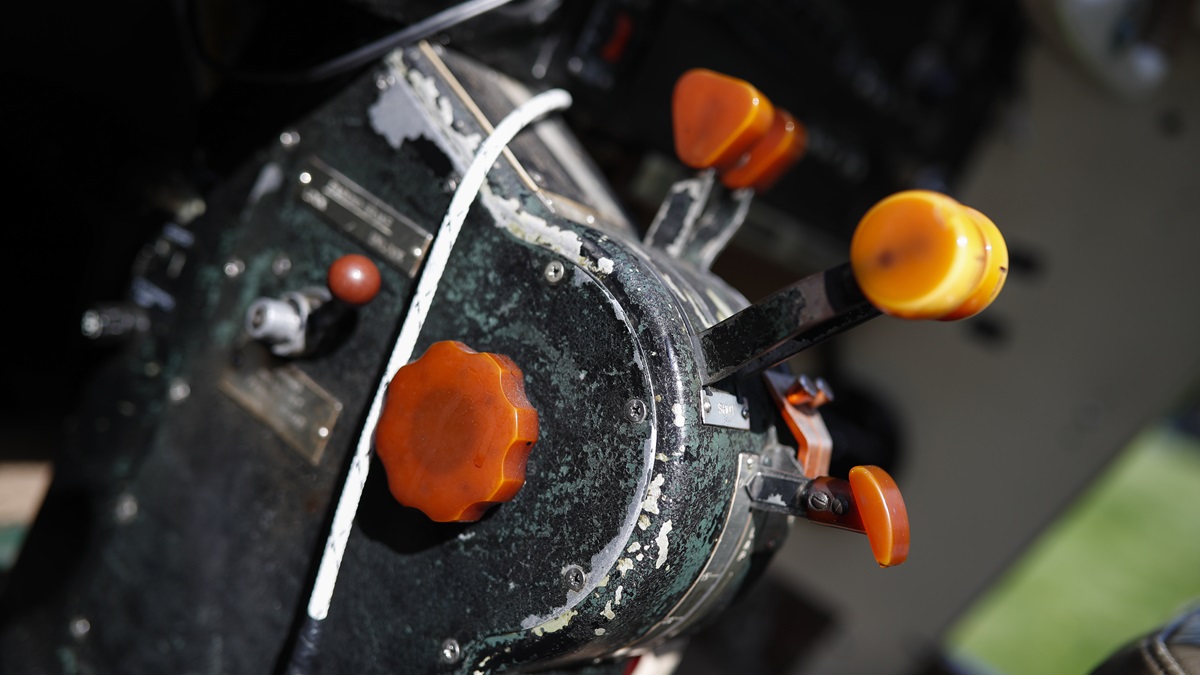

“Every piece of gray metal is new,” Van Wagnen said. “The engines are fuel injected and came from Helio Couriers. The props are from a Twin Bonanza.”

Both Van Wagnens are airframe and powerplant mechanics, and Brian also is an FAA designated engineering representative, so they do most of their own specialized Widgeon work. They’ve increased its fuel capacity to 200 gallons, and it now can carry avgas in the wing floats.

Their next planned upgrade is modernizing the instrument panel, a step that will include adding an autopilot.

“I like taking this airplane on long trips,” he said. “And when I do that, I want to be at high altitude listening to music—not down low dodging windmills.”

Van Wagnen is a veteran flight instructor and teaches in Grumman seabirds, including the majestic Albatross. The Widgeon is a favorite, he said, because of its history; its light, responsive handling qualities; and its demanding nature—especially on the water.

Add full power to both engines at the same time during a water takeoff and the nose moves left, regardless of rudder position. Touch down too fast and the Widgeon will skip; too flat and the nose will dig in; too slow and it will porpoise, beginning a series of divergent oscillations that can damage or even destroy the airplane. Fail to respond properly and promptly to an engine failure and the Widgeon won’t climb.

“The Widgeon’s got some idiosyncrasies on the water with porpoising” Van Wagnen said. “But that’s no big deal. It’s all about training. Once you know the airplane and understand what’s going on, it’s an incredibly fun and capable airplane to fly.”

Water world

Our fly-off began with a series of water takeoffs and landings performed individually on a narrow lake at an elevation of about 1,200 feet msl. Both airplanes carried about 60 gallons of fuel with two people aboard.

The Gull had a faster approach speed and flew final approach at about 85 mph, roughly 10 mph higher than the Widgeon, and touched down at 80. By using reverse thrust after touchdown in the Gull, however, both airplanes stopped in about the same distance.

“Reverse thrust is just cheating,” Van Wagnen said of his rival. “Not fair.”

Water takeoffs are surprisingly short in both airplanes. The Gull gets off the water in about 12 seconds, and the Widgeon is airborne in the same amount of time. Even though the Gull is a much heavier airplane, its big, thick wing and long flaps provide enough lift at low speed to make up for the additional weight.

Result: A draw.

Slow flight

Decelerating side by side at an altitude of 4,500 feet with flaps and landing gear up, the Gull and Widgeon remained steady and easily controllable to about 70 mph. Then their control responses became sluggish and their airspeed indicators became unreliable at high angles of attack.

The Gull is much heavier than the Widgeon, but the Italian design has a longer wing with more area.

Both pilots reported mild airframe buffeting at 67 mph and the Widgeon’s stall break took place at 62 mph indicated while the Gull kept flying. The stall break was benign, a slight nod, and recovery was immediate.

Next, both pilots extended the flaps to their limits and repeated the exercise. And this time the Gull stalled first at about 60 mph.

And when the Gull stalled, its right wing dropped about 45 degrees. Mohr immediately lowered the angle of attack with forward pressure on the yoke and opposite aileron, and it took about three seconds for the ailerons to become effective during the recovery.

“There he goes,” an observer in the Widgeon said of the Gull. “Man, he really unhooked.”

Result: Advantage Widgeon with flaps down. Advantage Gull with flaps up.

Roll rates

With the airplanes in a loose trail formation, the pilots began a series of banks left and right to see which airplane had the faster rate.

At an indicated airspeed of 120 miles an hour, they banked 45 degrees left, then right, simultaneously. Both seabirds had astonishingly quick roll rates of about 50 degrees per second, and both have substantial adverse yaw requiring coordinated rudder in the direction of roll.

The Gull is certified in Europe in the acrobatic category and is approved for loops and rolls, but here it’s registered in the utility category.

“I think we’ve got the better roll rate,” Mohr said. “This thing is pretty spritely.”

A review of the video shows that assessment is true—but the margin is razor thin. A close win is still a win, though.

Result: Advantage Gull.

Speed dash

The all-out drag race was the most surprising part of the contest.

Both pilots expected the smaller, lighter Widgeon with the same engines as the Gull to be faster. Their indicated airspeeds in flight also suggested the Widgeon would have a speed advantage.

But when both airplanes opened the throttles and turned up the prop rpm, they stayed together almost exactly. During the three-minute race to overtake the photo ship, the Gull crept ahead by about 10 feet.

“The old Gull is holding her own,” Van Wagnen said admiringly from the left seat of the Widgeon. “I think it’s faster by maybe a knot, if that. It’s hard to see a bit of difference in top speed.”

“That was a photo finish,” Mohr said after passing the Bonanza. “We were nose to nose.”

Result: A draw.

Gorgeous bird

Looking at them now, it’s hard to believe that neither the Gull nor the Widgeon enjoyed much commercial success in their era.

An American industrialist, Francis Trecker, went to the Piaggio factory in Genoa, Italy, in 1953 and began importing Gulls to the United States for luxury transport a year later. But his “Royal Gull” company shut its doors after about 30 airplanes were brought here and fitted with new engines and avionics.

The Gull was better known overseas where Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis owned three and King Farouk of Egypt had one. Eventually, Piaggio took what it knew about twin-engine pusher designs and focused on a land airplane, the P.166. That begat a long series of turboprop development culminating in the sleek, high-flying P.180 Avanti.

The Widgeon went through several iterations and upgrades over the years, and the McKinnon engine conversions in the 1960s offered major performance enhancements. But the miniature version of Grumman’s larger, radial-engine seaplanes was a distraction from the publicly held aerospace firm’s grand post-World War II ambitions, and the company focused on more lucrative military contracts.

Today, decades after they first flew, it takes a special kind of pilot and owner to keep these sublime, mechanically complex airplanes in top condition, and to fly them with precision. Very few have the flying skills, mechanical knowledge, or resources to make all that happen.

John Mohr and Brian Van Wagnen have those special talents and desire in abundance. They tend to their airplanes joyfully and fly them with easy grace.

“The main thing I took away from this experience was learning that your airspeed indicator reads about 10 knots fast,” Mohr laughed. “All this time, I thought your airplane was faster than it really is.”

“The biggest surprise to me was finding out just how closely matched these two airplanes really are,” Van Wagnen said. “Their performance in most categories is just about identical. Flying beside you and your Gull was just a ton of fun.”