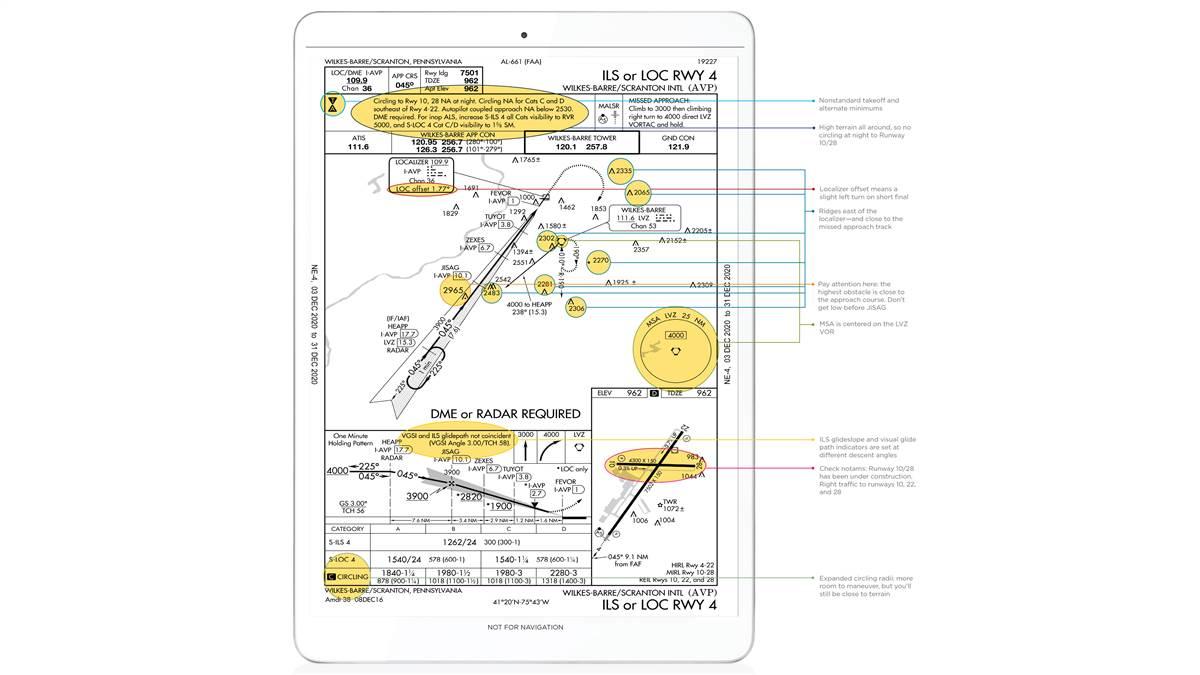

Chart Talk: (AVP) ILS Runway 4

Turbulence, icing, and a cliff on final

The ILS to Runway 4 is offset by 1.8 degrees because of the terrain and obstacles along the approach course. Adding to the fun is a steep drop at the approach end of the runway, basically a mini-cliff. There is no “landing short” here. Instead, you’d make impact with vertical terrain. EMAS beds are installed at both ends of Runway 4/22, but I can assure you that landing in an EMAS (engineered material arresting system—an area of crushable material designed to stop an airplane that goes off the end of a runway) will not end well. When the winds are howling here, and the ride is bumpy, keep this in mind. Coming in during high-wind and/or low-visibility conditions at night can be disconcerting.

The approach itself is not terribly complicated. The inbound course is 45 degrees, but the runway alignment is 44 degrees. The MSA (minimum sector altitude) is 4,000 feet because of the terrain just east of the final approach course, and that MSA is centered on the VOR, which is set atop that terrain. A close look at the terrain under the final approach will show that the highest obstacle is a tower that tops out at 2,965 feet msl, just west of the course prior to JISAG. There are some shorter towers just east and inside of JISAG, and another that sits between TUYOT and FEVOR.

There are several important notes on the approach: DME (or GPS) is required, no circling at night to the intersecting runway; and an autopilot coupled approach below 2,530 feet is no bueno. There are also some recommended crossing altitudes in the event that the glideslope is out of service. Most notable is that the DA is only 300 feet, which is 100 feet higher than standard, to allow for the slight turn to final that will be required because of the offset. If the glideslope is out, you will need a ceiling report of 600 feet.

At night, the effect of the approach lights being so high above the terrain can lead to a feeling of floating over the ocean, almost like a carrier landing.

The missed approach is worth noting as well, because the hold at the VOR is right at the MSA altitude of 4,000 feet, over hilly terrain. It’s also important that you climb to 3,000 feet before starting the turn toward the VOR. Something worth remembering is that in winter, if the ceilings are low, ice may be present—so make sure that you’re comfortable with the possibility of an approach in icing conditions with a missed approach that would take you toward hilly terrain with a potentially unknown amount of ice.

I’ve flown this approach too many times to count, and as I said at the beginning, it’s usually a nonevent. But when the winds start blowing over the hills and valleys, it becomes a different animal entirely. Low visibility can increase the pucker factor as well, and a deliberate mindset about the challenges of the terrain is a must. If you are in a crew, maximize the CRM—crew resource management—to stay ahead of the airplane, and you’ll be fine. If any deviations start to develop, go missed and try again, or start heading for your alternate.