Proficient Pilot: Cockpit catnaps

If you don’t snooze, you could lose

Although midnight local time, the sun refused to die. The northern horizon was a muted band of polar twilight and the ice below a pale, purple haze.

We had endured a lengthy departure delay and were hours behind schedule. The captain was tired, shifting restlessly in his seat while trying to find a comfortable position. He finally gave in to the fatigue and tilted his seat aft. “I know it’s not legal to sleep in the cockpit,” he groused, “but there’s nothing in the book that says I can’t faint.” Moments later he was out. Gone. The flight engineer and I were on our own on the flight deck, an occasional snore-whistle breaking the silence.

At least this captain was direct about his need to nap. Others, I discovered, preferred a different approach. They would simply close their eyes and claim to be studying a checklist tattooed to the insides of their eyelids. I was initially amused by such ploys—until discovering for myself what an efficient method of study this can be. Although some might criticize catnapping during the calm of cruise, this is certainly preferable to fading on final. No joke, that happens.

I have flown with crewmembers so wiped out during red-eye flights that they fell asleep during the approach. I recall once landing into a blinding sunrise at JFK after having been on-and-off duty for more than 16 hours. We were numb. After turning off the runway, my first officer switched to ground for our taxi clearance. But instead of being cleared, we were advised to return to tower. Puzzled, we complied. The controller could hardly contain himself as he asked us if we would now like to have our landing clearance.

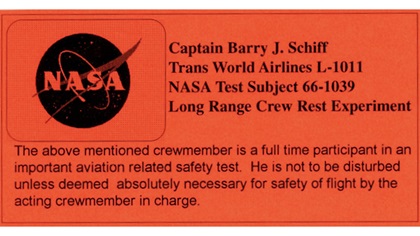

Such fatigue often is the result of being scheduled by computers that cannot always sense when pilots have had enough. Although there have been some positive changes to the working conditions of those who spend a great deal of time flying on the back side of the clock, more relief is needed. This should include encouraging the FAA under certain circumstances to make honest pilots out of those who can truly justify a cruise snooze, which—under controlled conditions—is much safer than falling asleep on final.

When the lone general aviation pilot becomes fatigued, his only option is to land and rest. Unfortunately, many of us feel compelled to push on when we should be in bed. Pilots who drive themselves this way may be involved in many more accidents than we realize because the physiological evidence often does not survive the crash.

Accidents resulting from pilots falling asleep at the controls most likely occur between 0000 and 0600 local time. Unless investigators can determine that the pilots were seriously fatigued and had been “holding their eyelids open with toothpicks,” such accidents are simply and perhaps incorrectly attributed to spatial disorientation or controlled flight into terrain. They know intuitively but might not be able to prove that many otherwise inexplicable accidents were caused by pilots flying beyond their endurance limits.

Several years ago, my good friend Richard Somers and I flew a Beech Debonair from the East Coast to West. We reluctantly opted to fly through the night because Somers had to be in Los Angeles the next day for a business meeting. Weather forced us onto a southern route over the swamps of Mississippi and between layers at oh-dark-hundred. The world beyond our windshield was black and featureless. I do not recall whose idea it was, but we turned off all interior and exterior lights just to see how dark it really was. It was as black as black can be. We saw nothing and began losing reference to time and space—at which point we began to experience a mild form of hallucination likely exaggerated, we were told, by fatigue. The cockpit quickly became a flurry of hands groping for switches. We could not turn on the lights soon enough.

Tired writers, I understand, also need to recognize when it is time to rest.