Flight Lesson: Chased down final

Too close for comfort

By Christopher L. Freeze

The traffic pattern of a general aviation airport, especially on a sunny weekend, can be a symphony of beauty. It can also be a madhouse!

On a recent Sunday afternoon, I was working with a presolo client on his first flight where he felt confident enough to make radio calls. Staying in the traffic pattern of Leesburg Executive Airport (JYO) in Virginia, the communications were expected to be repetitive: receive clearance from the control tower and repeat what was issued. At least that was the plan.

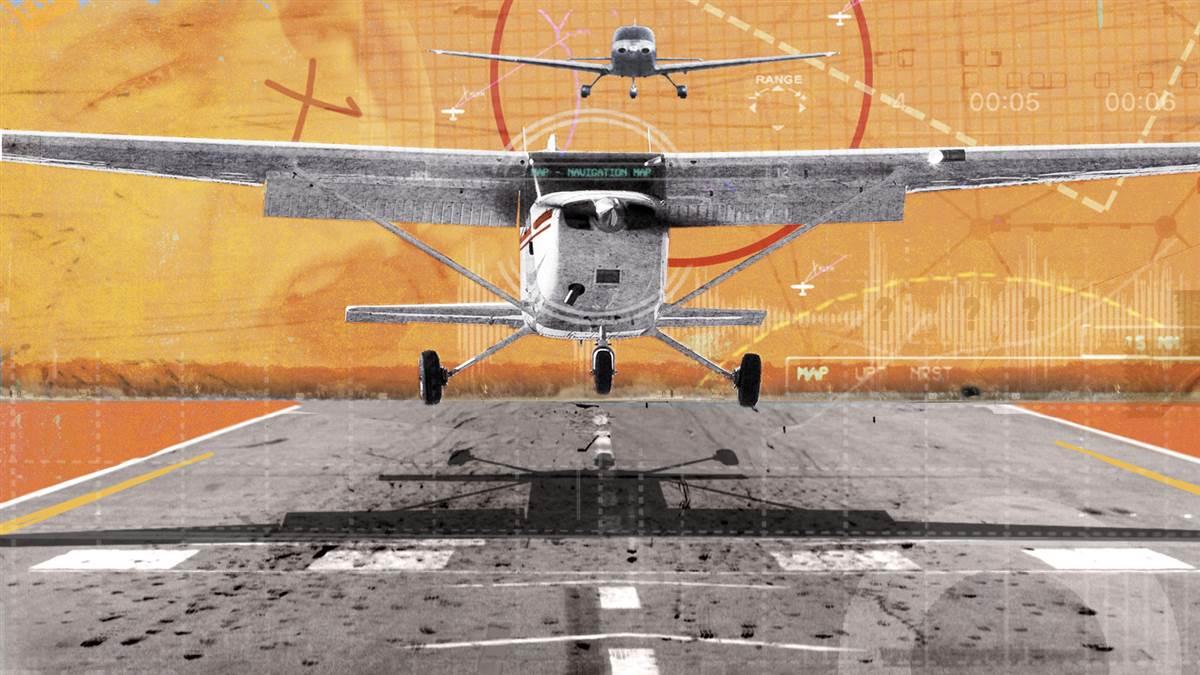

After an uneventful takeoff into the pattern, it was quickly apparent that instructors and students from every local flight school had a similar idea, as the G1000’s multifunction display (MFD) in the Cessna 172 my student and I were flying showed a full pattern of five aircraft—plus our own. Airplanes practicing instrument approach were interrupting the choreographed routine, as were departing aircraft on IFR plans.

My student did his best with the radio, rehearsing proper phrasing before pressing the push-to-talk button on the airplane’s control yoke. But every needed readback resulted in his face becoming awash in befuddlement, leaving me to bail him out. The rapid-fire instructions of the tower meant no time for a newbie’s learning curve to catch up.

Overall, my student’s traffic work and landings were above average for his experience level. But I did have to intercede on one of the last circuits of the day.

For most of the flight, we were behind a Piper Cherokee and cleared as “number two” for the option onto Leesburg’s Runway 17. On this pattern, however, a Cirrus reported a five-mile approach to the runway. As we turned onto the base leg, the controller cleared us as number two to the runway between the Cherokee and the incoming Cirrus. We read back the clearance and continued our downward flow to the runway.

On the MFD, the once sizable gap between the Cherokee and the Cirrus for us to wedge between was rapidly closing, because the Cirrus was not slowing down. I saw it as we began the turn onto final, as the controller inquired to the Cirrus if he had the traffic in sight.

“In sight,” its pilot claimed, in a hurried voice. But I wondered, he is not slowing. Is he referring to me or the Cherokee ahead?

On the MFD screen, the Cirrus was depicted to be 300 feet above and behind us, with the gap closed to a point where its vector line (which depicts the direction the target is moving) bisected us. As we were in a high-wing airplane, we couldn’t look up and behind to confirm its position.

“You sure he sees me?” I said to the tower controller. “The scope shows him halfway up my tailpipe!”

“Looks fine from here….” the controller replied. The pilot in the Cirrus was silent.

Given what the MFD showed and since we were already zooming over the runway numbers at 100 knots to keep some space between us, I elected for a go-around.

Seconds later, the Cirrus landed, seemingly unaware and carefree.

As the traffic over the field subsided to where only we remained, I asked the tower what he saw when we executed our go-around and—according to him—there was at least a half-mile between the Cirrus and us.

The controller reminded me that the traffic system on aircraft could have a few seconds of lag, and have other inaccuracies as well. And while I know and understand this, the MFD screen told me I was in a potentially dangerous situation. And the fact is, I will do what I can to determine my fate in the air, not hope on someone else.

Christopher L. Freeze is a CFI from Virginia.

WHAT HAPPENED

WHAT HAPPENED