Self-made motion picture pilot

Fred North flies helicopters for Hollywood movies with big budgets directed by seasoned pros who have a thirst for dynamic footage that often leaves little margin for error. He has no fear of losing his job to a drone.

Some of the most eye-popping aerial cinematography to be found in today’s action films is not the product of digital sleight of hand, but skillful, close-quarters flying by a handful of helicopter pilots known as stunt film pilots. The best of them combine thousands of flight hours of experience, an innate sense of the camera, and an almost telepathic link with their favorite camera operators to bring audiences to the edge of their seats.

Thanks to a fortuitous connection, North soon found himself aboard an Aérospatiale Alouette II, sans doors (thanks to its photo mission), a flight that inspired what has become a 20,000-hour career.

“All my life I will remember holding the seat because I thought I was going to fall out of the helicopter,” North said. “It was horrifying, but at the same time it was amazing.”

North has been flying for motion pictures for more than 26 years and is sought after by directors such as Michael Bay (Pearl Harbor, Armageddon) because of his success in translating a director’s vision into maneuvers that produce footage fit for a feature. Based in Los Angeles, North, a citizen of France and the United States, has traveled worldwide to apply his creative touch to more than 200 films. You may have seen his work in San Andreas, Spectre, or Mission Impossible-Rogue Nation, among the scores of films he has flown for.

North, in a recent Zoom conversation, offered aspiring film pilots a peek into his world, and some advice for getting there if they have the passion and the talent. Now that drone footage is showing up routinely in television and film, one might think a helicopter pilot who makes his living on location would be wary of the newcomers who fly with both feet planted firmly on the ground. Rest assured that he is not. In fact, it may surprise you just how little overlap he sees between manned and unmanned aviation in the context of making movies.

‘I decided to create that position’

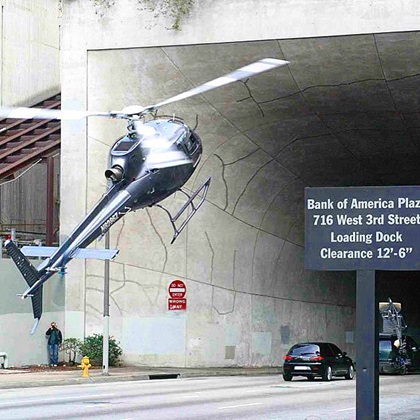

North built a career that paid for his Eurocopter AS 350B3, a three-bladed, five-passenger turbine workhorse (also known as an Airbus Helicopters H125 and marketed as the AStar in North America). Countless clips on social media showcase the virtuoso skill of a pilot well-versed in the cinematic arts, with no evident fear of ground proximity. With 847 horsepower at his command and a gimbal-mounted camera in front of his feet, North earned a reputation for his painstaking approach to safely executing dynamic action sequences.

Like any master craftsman, North is particular about his equipment: For foreign assignments, he has amassed a stable of carefully vetted helicopters in various locations around the world that he can rent knowing that they are maintained to his satisfaction. This allows him the confidence to fly them like he flies his own.

This confidence is particularly important when he is slinging himself and a camera operator around at high speed within a few feet of vehicles, buildings, lampposts, and other structures, often very close to the ground. His assignments routinely take him through tunnels, under bridges, and up narrow ravines.

It takes years of experience to do what North does safely, and he was not flinging his aircraft to and fro on his first day. He obtained his commercial pilot certificate in a helicopter in France at age 21, launching a career that began simply and humbly barnstorming in a three-seat Bell 47 (famous worldwide for its distinctive bubble canopy). North hawked tours with a loudspeaker mounted on his car roof. Like a small-town carnie, he would move from village to village seeking new customers.

Realizing that flying tours was not his endgame, and with 1,200 hours under his belt, North shifted gears: His second and third years of commercial flying were filled with utility and rescue work in the French Alps, including long line flying. The term is aptly named as it involves hauling cargo slung from a long line beneath the helicopter. In these roles, North gained considerable experience and confidence managing external loads and departing from straight-and-level flying.

Having found vestibular stimulation to his liking, North decided he wanted to do film work. He flew television cameras for events like the Tour de France and Formula One races. North would soon realize that there is a tremendous difference between flying 500 to 1,000 feet above race cars tearing around a track, and a more intimate chase that creates emotion through flying close to the subject, using his helicopter as an extension of the camera. In France, the notion of a “film pilot” didn’t really exist. Earning that distinction would separate North from the pack and propel his career.

In 1996, a U.S.-based camera operator recruited him for a film shoot in Venezuela. The job called for a European-licensed pilot, and North applied his previous flying experience to his first motion picture gig, earning in three weeks of work the same amount of money he had earned in a year of flying television cameras in Europe. With that lucrative, eye-opening experience, North was ready for more.

“I decided to create that position in France,” North said.

‘It’s a challenging job’

In some respects, flying a dynamic, low-level film mission is like any other well-planned flight: You start with the desired outcome, plan the mission, review any and all potentially unsafe aspects of the mission, learn everything you can about the environment, and ensure your crew (both on board and on the ground) know the mission well before you think about starting the engine.

“Sometimes, we’ll do a walk-through ten times,” said North, who typically spends two months planning complicated sequences. Some of that time involves obtaining approvals and negotiating the removal of low-level obstacles such as streetlights, stop signs, and overhead wires. He emphasized a collaborative approach with regulators, noting that he brings the FAA in early and thinks of them as part of the team, rather than as an adversary.

There are a few unique aspects to flying Hollywood movie cameras, beyond their rather impressive size and weight.

If the director North is working for is not known to him, North first watches the director’s last two films to examine the director’s approach to action and how it’s created. He wants to know the director’s signature. Then comes the “fishing expedition,” where “I go see the production designer, the producer, the director of photography, the assistant director, and I ask lots of questions.”

The helicopter is also prepared with care, its gyro-stabilized nose mount fitted with video or film camera equipment that matches that being used on the ground. This way, aerial footage doesn’t have a different look and feel from the ground action. This process can take from several hours to an entire day. Counterweights on the tail boom and tailcone compensate for the 250-pound protrusion that extends from the nose and balance the aircraft.

North typically works with one of three photographers on whom he has come to rely for their consistency. They work as a team, but don’t speak much as they fly and film. North keeps two small monitors mounted to his left and right, and the camera operator has a larger monitor in the rear. The monitors up front become part of North’s constant scan.

“If you understand what the shot is, and we both have the same vision, we don't need to talk,” North said.

When flying, the video from the helicopter is transmitted live to the director on the ground. If any communication is needed between ground and air, that is handled by ground pilot coordinators, usually pilots themselves, who can speak concisely using terms North can translate quickly into another approach.

Ground pilot coordinators also help North safely fly down streets flanked by structures just a few feet from his rotors. A spotter warns him on the radio if he slips off the planned course by even a few inches. North will sometimes lay down strips of tape on the ground that he can follow in tight quarters.

‘It’s never a competition’

Carefully planning a helicopter flight down a street crowded by structures on both sides naturally leads to discussions about safety, risk mitigation, and, these days, whether drones are potentially safer and cheaper substitutes. Sometimes they are, often they are not. North’s take on this begins with two precepts.

First, when speaking strictly about stunt film flying, drones and helicopters have perhaps only 5- or 10-percent overlap in terms of mission capability, North said. Rarely are both ideally suited for a given job.

“People get confused about what drones do and what helicopters do. When you do drones, you don’t fly the camera, because you fly the drone. When I’m flying the helicopter, the camera is in front of me and I’m connected to it physically. We (the pilot and camera operator) create the action, while the drone will tell the action.”

North said a director might ask a drone crew to follow a car from above, or capture an establishing shot, often spelling out the shot in detail. In contrast, his own instruction is often along the lines of, “Fred, do your thing and get me something cool.”

North’s second precept is that he just doesn’t fly missions that aren’t safe: “If we don’t think what we’re doing is safe, we’re not going to do it.”

North believes that choosing between a drone and a helicopter is less about safety or cost than it is about the desired final product. He again employs the emotion-and-creativity versus documentation comparison.

North asserts that by actually being attached to the camera as he flies, he is much more aware of perspective, distances, spatial orientation, and timing than a drone pilot who might be hundreds of feet away from the camera, with remote perspective and limited depth perception.

To illustrate his point, North recalled watching three drones crash while attempting to film a car chase. North says the crashes occurred “because they were trying to get as close to the cars and trucks (as possible) but didn’t have the vantage that a helicopter pilot would, so they ran into the vehicles.” But, he said, “I’m not throwing anyone under the bus. It’s a challenging job for them and for us.”

Often on the set with (and flying at the same time as) the drone crew, North added: “It’s never a competition because we’re not getting the same shot.”

Rest and reflect

At the close of any day’s shooting that called for flying to the edge of his self-imposed limits (“kissing the red,” he calls it), North finds quiet time to analyze his performance to see if everything was done as planned. He considers this critical to safe flying and keeping himself honest. He noted that 200-hour pilots and 10,000-hour pilots can both make mistakes.

North said drones do have strengths that make them the right tool for certain shots, though the perceived lack of risk can work against unmanned aircraft operators. He has sympathy for young drone pilots who feel they can’t say “no” to a director’s request. Drone pilots, who are often less experienced, can feel pressured to overreach their machines’ capabilities, or their own (or both). They might lack the confidence and interpersonal skills to tell a director or producer that something in the plan is unsafe and suggest an alternative.

It is different for pilots who will be risking their own necks. North recalled feeling uncomfortable with a locally based helicopter lined up for filming at the southern tip of South America. The producer protested the $120,000 cost of ferrying in an aircraft that met North’s requirements, but the matter was put to rest when North asked the producer to accompany him when flying the local helicopter. The more expensive helicopter was ferried in.

North advises aspiring cinema pilots to challenge themselves on the way up the ladder. Sightseeing tours build time, but critical skills are learned by doing more complex flying, such as long line work, medical rescue, or firefighting.

Once the basic skills are honed, one path to Hollywood is to follow North’s example and acquire your own stabilized camera rig, and rent it out—with you as the pilot. North did this for five years, charging nothing for his flying time, using partnership helicopters to build his portfolio. As he became better known, he began to charge for his flying. Having an eye for composition, lighting, and framing the action is essential; demonstrating that ability will bring in more work. If you don’t have a good eye, directors will know it from the footage.

“Don’t go for charter or flatland work, and don’t try and shortcut the process,” North said. While there is more to landing this kind of job than the hours in your logbook, it’s not impossible to work your way into the close-knit industry, North added. “There is always room for others. If you want to do something and you are good at it, then just do it.”

View some of Fred North’s flying on his Instagram.