Savvy Maintenance/Opinion

Blowout! Planning for the unplanned

He lives in Los Angeles, a couple of hundred miles southwest of where we live. It’s a pretty miserable four-hour drive by freeway, so I’d offered to fly her there Wednesday morning and to bring her back the following Saturday.

He lives in Los Angeles, a couple of hundred miles southwest of where we live. It’s a pretty miserable four-hour drive by freeway, so I’d offered to fly her there Wednesday morning and to bring her back the following Saturday.

The closest general aviation airport was Jack Northrop Field in Hawthorne (HHR), just southeast of LAX. It would be 55 minutes down and 45 minutes back in my Cessna 310. I landed on Runway 25 and dropped her off at the FBO (Hawthorne Hangar Operations, aka HHO), then flew back home to Santa Maria (SMX).

Bright and early Saturday morning I launched for Jack Northrop Field again. SoCal Approach routed me over LAX at 5,000 feet, followed by a circuitous route to intercept the Hawthorne GPS Runway 25 approach. Hawthorne tower cleared me to land on Runway 25. I crossed the boundary at 90 knots, touched down softly about 500 feet past the threshold, rolled another 1,000 feet or so while gently lowering the nosewheel, then started braking in anticipation of making a left turn off the runway toward HHO where my fiancée was waiting. Everything was going perfectly until…

Suddenly, without warning, the aircraft started pulling hard right. I stomped on the left pedal and applied left brake and differential power, but nothing I did succeeded in arresting the right turn. The airplane headed off the right edge of the runway despite my futile efforts to regain directional control.

Then the right wing started to drop, and I instantly realized what had happened: My right main landing gear tire had gone flat! In more than 55 years of flying GA airplanes and 32 years of flying this Cessna 310, this was the first time I experienced a blowout.

The airplane came to rest on the apron headed perpendicular to the runway. It didn’t want to roll any farther, and I was not inclined to apply a lot of power for fear of inducing a prop strike or damaging the relatively soft aluminum wheel. I pulled the mixtures to idle cutoff and keyed the mic: “Hawthorne Ground, Twin Cessna two-six-three-eight-Xray is immobilized with a flat right main gear tire and will require assistance.” I then powered down the electrics, egressed the airplane, and waited for assistance.

While waiting, I surveyed the situation. There was a lot of good news. The right main tire and tube were pretty much shredded, but the wheel looked undamaged. So did the outer gear door and the propeller tips. I searched for other evidence of collateral damage and found none.

The airplane had stopped on a hard-surfaced apron that was painted green (to simulate the look of grass?) and which I later learned ATC referred to as “the Green Zone.” That it was asphalt rather than grass or dirt should certainly make it easier to jack the airplane, I thought, and the fact that I didn’t take out any runway lights seemed like a stroke of luck.

Gosh, it’s quiet

About 10 minutes into my survey, I realized it was awfully quiet. No airport vehicles or first responders had arrived at the scene of my immobilized airplane. No other aircraft had landed or taken off.

About 10 minutes into my survey, I realized it was awfully quiet. No airport vehicles or first responders had arrived at the scene of my immobilized airplane. No other aircraft had landed or taken off.

Although the airplane was clear of the runway, it wasn’t far enough clear to allow the tower to reopen the airport—normally very busy, especially during the weekend. And even though I’d notified the tower that I required assistance to extract the airplane from the Green Zone and allow the airport to reopen, no assistance seemed to be forthcoming.

I called HHO on my cellphone and spoke to Andre who was in charge there. I explained I was right across the runway from him with an aircraft immobilized by a flat tire and needed assistance. He promised he’d make some phone calls and see if he could scare up some help. He must have done so, because about five minutes later I saw a golf cart approaching, and shortly thereafter an impressive Lektro tug that looked like it was designed to move Gulfstreams and Challengers. I figured these guys had lots of experience dealing with flat-tire incidents and would know exactly what to do.

I figured wrong. They started discussing how to move the airplane and proposed a variety of ideas. I found myself in the unexpected role as a spoiler, shooting down each of their proposals with “no, that’s not going to work because…” or “no, that would damage the airplane.” It quickly became apparent that we were working at mildly cross purposes. The airport workers understandably wanted to get my airplane away from the runway ASAP so the airport could reopen. Equally understandably, I wanted to make sure that my airplane would still be flyable after the airplane was moved—once the trashed tire and tube were replaced, of course.

In my work, I’ve had dozens of clients whose GA airplanes were immobilized by gear-ups or prop strikes, and it’s common for the aircraft to sustain more damage during the recovery process than during the initial incident. I was not about to let this happen to my airplane.

A pickup truck arrived on the scene. It had been dispatched from Security Aviation, the sole maintenance shop on the field. In its bed was a smallish-looking aircraft jack. I showed the fellow from Security where the right wing’s jack point was located, and we moved the jack into position.

Fortunately, the jack was short enough to squeeze under the wing even with the flat tire. Unfortunately, the jack was not tall enough to raise the wheel off the ground even at its maximum extension. I asked the fellow from Security whether he had a taller jack. Yes, he said, but that one was too tall to squeeze under the drooping wing. By now, the airport had been closed for a half-hour and we were back at square one.

A savior arrives

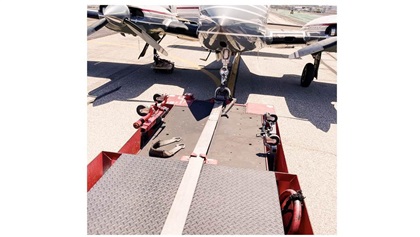

At this point, another mechanic arrived from Security Aviation. He introduced himself as Chris Miller, lead mechanic. Miller sized up the situation and soon came up with an action plan that sounded like it might work. His idea was to place a steel dowel into the hollow part of the axle, use an automotive floor jack to lift it just enough to remove the wheel from the axle, slide a furniture dolly with some plywood placed on top of it under the axle, and then lower the axle onto the plywood-covered dolly and lash it in place with a nylon strap. This would hopefully result in the airplane becoming carefully towable by the Lektro tug.

Happily, Miller’s plan worked. We removed the wheel, set the axle onto the dolly, and gingerly towed the airplane to a spot just in front of Security’s maintenance hangar at the northwest corner of the airport. Since it was Saturday and Security Aviation didn’t happen to have any 6.50X10 tires or tubes in its parts room, that’s about all that could be accomplished until Monday morning.I explained to Miller that the wheel was secured to the axle using a nonstandard True-Lock fastener that required a special wrench to remove. Fortunately, I had that special wrench in the toolbox I always carry in my left-wing locker, together with all the other tools needed to remove the wheel and brake assembly. I also pointed out to Miller that we’d need to disconnect the outer gear door and tie it back to prevent it from being damaged during the jacking and towing procedures, something Miller accomplished using several long nylon tie-wraps that one of the guys managed to come up with.

Happily, Miller’s plan worked. We removed the wheel, set the axle onto the dolly, and gingerly towed the airplane to a spot just in front of Security’s maintenance hangar at the northwest corner of the airport. Since it was Saturday and Security Aviation didn’t happen to have any 6.50x10 tires or tubes in its parts room, that’s about all that could be accomplished until Monday morning when Desser Tire & Rubber Co. would open.

So now what?

I finally met up with my fiancée at HHO. We were both starving by now, so we found a nearby restaurant and discussed our options. Since she seemed anxious to get home and I’d neglected to bring a change of underwear, a toothbrush, or (most important) my laptop, we decided our best bet was to rent a car and drive home (three to four hours); then I’d hit the road early Monday morning, drive to Desser’s headquarters in Montebello, California, to buy the tire and tube, and then drive to Hawthorne to fix the airplane and return the rental car.

We finally arrived home about 10 p.m. Saturday. Sunday, I went to the Desser Tire & Rubber website to order a new tire and tube and a set of new brake linings. In the comment field of my online order, I said “Do not ship. Hold for will-call pick-up at Montebello.” Then I hit the sack early and set my alarm for 2 a.m.

I was on the road by 3 a.m. and ran into moderate freeway traffic. The GPS estimated my arrival at Montebello at about 7 a.m. At 6:30, I phoned Desser from the car just to make sure they would hold my order for pickup and not ship it out. I reached a nice lady in sales who looked up my order and then explained to me that Desser no longer stocked anything at its Montebello headquarters, and had moved its stock to a warehouse in San Bernardino!

“I can do San Bernardino,” I told the woman. “Can you please make sure they hold it for me there?” She said they’d have the tube and brake linings for me at San Bernardino, but that the 6.50x10 six-ply tire I’d ordered would be coming from Texas. “Texas won’t work,” I protested. “This is an AOG aircraft.” After a bit of back-and-forth, I learned that they didn’t have any 6.50x10 six-ply tires in California, but they did have lots of 6.50x10 eight-ply tires at San Bernardino. “I’ll take them!” I said and asked her to amend my order and make sure that the tire would be held for me at the warehouse.

I pulled off the freeway long enough to look up the address of Desser’s San Bernardino warehouse and program it into my phone’s navigation app. I got back on the freeway and arrived at the warehouse about 8 a.m. By 8:30 I had tire, tube, and brake linings in the trunk of my rental car and was back on the freeway. I texted Miller that my ETA at Security Aviation was 10 a.m.

Back togetherness

When I showed up at Security, Miller introduced me to one of his line A&Ps named Jared who apparently had drawn the short straw and was assigned to help get my Cessna 310 back in the air. Jared had already disassembled my wheel and cleaned it up nicely. It took him about 30 minutes to mount the new tube and tire on the wheel, and another hour to jack my axle off the dolly, install the wheel, lower the aircraft onto its feet, reassemble the brakes with new linings, and reattach the outer gear door while I watched and kibitzed. By noon, the airplane was ready to go.

Right after lunch, the paperwork was complete, I settled up with the shop for Jared’s two hours of labor, thanked him and Miller profusely for their invaluable help, and launched for home. By 3 p.m. the airplane was snug in its hangar, and all was once again right with the world.

No pilot wants to experience a blowout on landing, but I sure was fortunate that the airplane wasn’t damaged during the resultant loss of directional control. That it came to rest on a hard surface. That Chris Miller happened to be working on a Saturday and came up with a scheme for moving the airplane without damaging it. That I’d had the chutzpah to say no to a bunch of other schemes that surely would have. That I carried all the tools necessary to remove the wheel from the axle. That I managed to find a suitable tire in Southern California rather than Texas. And that Jared was available to help put the airplane back together so quickly and skillfully. All in all, it was an excellent outcome.