Risk stacking

When a series of challenges add up and equal disaster

Flying single pilot IFR in a Cessna 208B Caravan, she planned a familiar route: Salt Lake City (SLC) to Burley Municipal Airport (BYI) in Idaho, 133 nautical miles to the northwest.

Flying single pilot IFR in a Cessna 208B Caravan, she planned a familiar route: Salt Lake City (SLC) to Burley Municipal Airport (BYI) in Idaho, 133 nautical miles to the northwest.

She knew better than to trust the forecast and discussed the trip with her operations leader. This would be no “milk run,” the term coined by Allied pilots in World War II for flights with little danger. Not this approach, to this runway at this airport, in this weather. The day before, the pilot had attempted the same run and been forced to divert. Spring weather in Idaho, always precarious, seemed especially volatile this year.

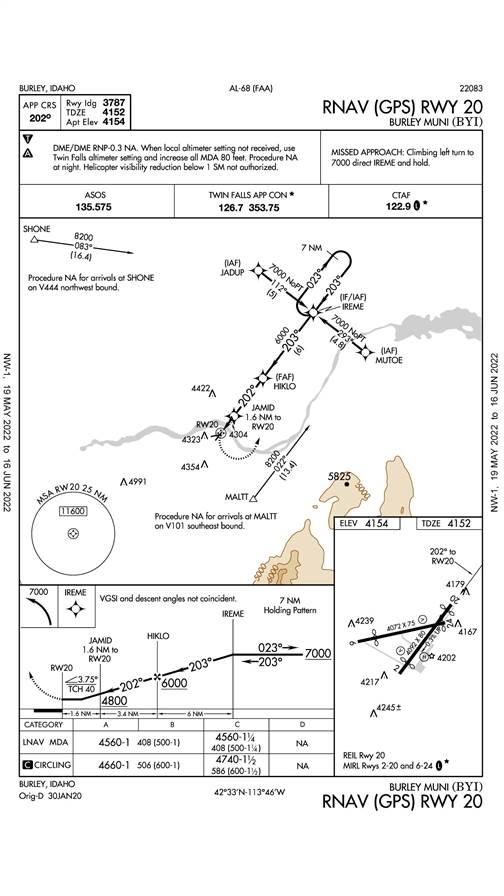

ADS-B data, camera footage, controller communications, and eyewitnesses all offer clues to the progress of her flight and the final tragic moments. FlightAware tracking data indicates an uneventful en route phase followed by a first approach to Runway 20 that appeared solid: precise course tracking, adherence to step-down altitudes, steady descent, although slightly steep. From the final approach fix to the minimum descent altitude, she descended around 1,000 fpm.

Rough calculations from ADS-B ground speed indicate she was fast on the approach, but close to her operation’s procedures, which call for 120 knots on approach until visual with the runway. She would have been comfortable at her speed, even if slightly fast, in a Caravan landing on a 4,000-foot runway with dynamic propeller pitch options (“beta”) for short landing roll.

She flew to the MDA, and went missed, continuing directly over the runway and into the published missed approach procedure, then directly to the initial approach fix for another attempt. The pilot flew outbound from the IAF on the procedure turn, then turned inbound and intercepted the final approach course. All seemed under control except for a short transmission that may have been a harbinger. After clearing her inbound, the controller asked if she had passed the IAF, she first answered negative, then subsequently replied that she had crossed the fix. Was this a sign that she was stressed, perhaps a little behind the airplane and a little confused on her position as she began the approach? Or was it just a misspeak, a small communications error?

Studying FlightAware tracks, it appears the pilot started a controlled descent, not quite as aggressive as her first approach. Notably, she was slower than her first approach, by some 25 mph according to ADS-B ground speed. She emerged below the clouds, in a nose-high descent, then according to eyewitnesses flew into a plume from the smokestacks that are less than a mile from the runway, directly on final approach. She powered up, nosed up, struck the smokestacks, and crashed onto the roof of an industrial building.

The nagging question is why? Why did she drop that low, that early? How did she go quickly from an approach that looked under control to disaster in a half-mile span?We know what happened: She was too low, too early, and hit the smokestacks. The nagging question is why? Why did she drop that low, that early? How did she go quickly from an approach that looked under control to disaster in a half-mile span? The unsatisfying answer is, we may never fully know. The NTSB, now early in its investigation, may not be able to determine why the flight unraveled. Small clues may offer insight. We may learn that several small items, not by themselves hazardous, collectively proved fatal.

Perhaps culture played a role. The day prior to the accident, scheduled on the same route, the pilot diverted. Did that indicate she was impervious to mission pressure? Or did the notion of missing a destination two days in a row put added pressure on her to make it in? Delivering freight on time into demanding places under tough conditions has been a proud heritage for freight pilots since 1910 when Philip Parmelee flew the first freight mission. He loaded a Wright Model B with 200 pounds of silk and flew to a retail store opening in Columbus, Ohio, beating a railroad express service.

Visibility certainly played a role. The pilot may not have recognized just how low the visibility dropped at Burley before she started the first approach. As she cruised en route, the METAR reported 6 statute miles in light snow and a broken ceiling at 2,600 feet, technically VFR. By the time she reached the IAF and began her approach, visibility had dropped to a mile and ceiling to 2,100 feet. A 2,100-foot ceiling is no help when visibility is only a mile. She handled it fine on the first approach, but not the second. Why?

ADS-B speeds are difficult to interpret and can be imprecise, but they are a potential clue. Did the speed variances between the two approaches indicate a pilot struggling for precision in demanding conditions? On her last approach, from near JAMID, a step-down 1.6 nm from the runway until the last solid ADS-B track a half-mile later, her speed dropped rapidly by 30 mph. If accurate, perhaps the slowing speed indicates she thought she spotted the runway and began slowing to landing speed. Perhaps the slower speeds throughout the second approach set her up for trouble in icing conditions. In a Caravan, the tail will ice first—a treacherous, insidious condition that can cause loss of control.

The smokestacks at Burley inside a mile on final were at least a distraction and at worst causal. They wouldn’t normally be a factor; a nuisance, yes, but not treacherous. Dozens of pilots had flown hundreds of approaches over those smokestacks and in poor weather. On this day, however, conditions were perfect for ruinous impact. She approached them almost directly downwind from the plumes, which would have been substantial on such a cold day. The FAA’s guidance warns against flying through smokestack plumes, especially on cold days: turbulence, airframe distortion, reduced visibility, engine problems, icing, flight control deficiency. Any of these could have occurred and would have been potentially serious in ugly weather so close to the ground.

The RNAV 20 approach into Burley has a high MDA and a steep, 3.75-degree vertical descent angle because of the smokestacks so close to the runway threshold, directly on the runway centerline. The steep VDA requires an aggressive descent from the MDA at the missed approach point to the runway. Did the first missed approach, and steep descent angle, nudge the pilot to get low, early, on the second approach, or did something else cause her to drop below the MDA? Something mechanical? Engine problems or structural icing? Did the emanations from the smokestacks cause problems that were unsurmountable in her flight regime?

Perhaps there was a visual illusion. Approaching Burley on the RNAV to Runway 20, the roof tops and highways could all appear to be a runway to a pilot yearning for visual pickup. Perhaps she descended below the MDA early believing she saw the runway, which turned out to be something different entirely. Then, she suddenly went back in IMC because of the plume and lost situational awareness and aircraft control. Perhaps.

Single pilot, in winter conditions, on a demanding approach, with nonstandard obstacle clearance, nonstandard vertical descent angle, directly over a smokestack, and downwind of a debilitating plume. Clearly all the factors proved too much. Our lesson learned may be the perils of risk-stacking. One risk element by itself may not be dangerous, but when we stack several of them together, the synergy is a negative accumulation that even the most talented and motivated pilots cannot overcome. It’s easy for us to identify the risks and stack them in hindsight, sitting casually at zero knots and one G. One takeaway from this tragedy must be that we learn strategies to identify our accumulating risks in the moment, and develop methods to recognize when the stack gets too precarious and it’s time to exit.

[email protected]

airsafetyinstitute.org