Facing the IPC

The return to currency

The regulations say that for carrying passengers, you’re current if you make three takeoffs and landings (to a full stop, for nighttime) within the 90 days. For instrument currency, FAR 61.57(c) says that in the six-months prior to the flight you must log six instrument approaches, fly “holding procedures and tasks,” and intercept and track courses “through the use of navigational electronic systems” before you can launch on an IFR flight plan, or into weather that’s below VFR minimums. Let your currency lapse for more than six months? Then you need to complete an instrument proficiency check (IPC).

The regulation governing IPCs (61.57(d)), which has no flight-hour stipulations, is vague when it comes to requirements. Pilots must demonstrate proficiency in ATC clearances and procedures; flight by reference to instruments; navigation systems; instrument approach procedures; emergency operations; and postflight procedures. And that’s all the regs have to say.

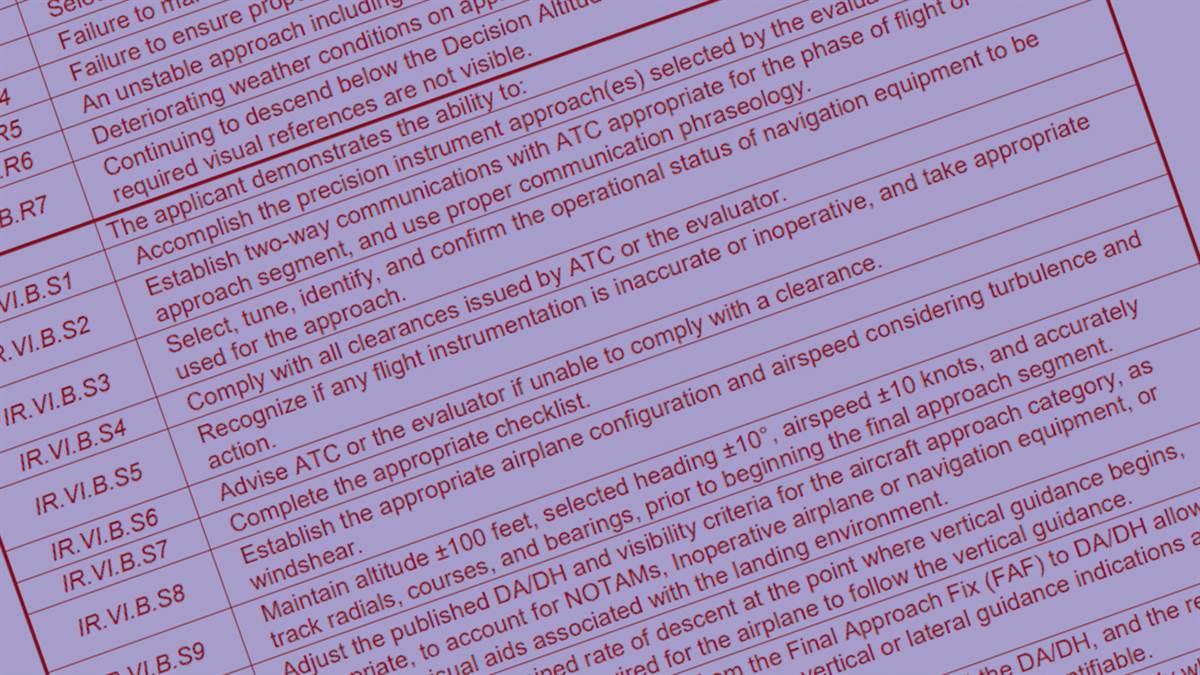

The airman certification standards for the instrument rating provides more detailed guidance, so a flight instructor evaluating you for an IPC will have you demonstrate—under the hood, of course—the following minimum tasks:

- A precision approach.

- A nonprecision approach.

- A missed approach.

- A circling approach.

- Holding.

- Landing(s) from a straight-in or circling approach.

- An approach with the loss of primary flight instruments.

- Recoveries from unusual attitudes.

- Intercepting and tracking navigation courses.

Of course, an instructor can also mix things up. Those approaches may end up with missed approaches, complete with a holding pattern—or end with a circle-to-land maneuver. And all those approaches must be stabilized approaches, with no more than three-quarter-scale deflection from the lateral and/or vertical guidance bullseyes and flown within plus or minus 10 knots of a target airspeed. Then again, expect the unexpected. You may be asked to explain the rules for selecting alternate airports or quizzed about obstacle departure procedures, lighting systems, or autopilot procedures. Multiengine pilots will have to fly a precision approach to a landing with an engine out, plus demonstrate turns and straight-and-level flight.

In fact, you may have to satisfactorily perform any number of tasks listed in the Instrument Rating Airman Certification Standards. In other words, an IPC is designed so that an aspirant can prove he or she can competently fly all the tasks they flew back when they passed the instrument rating checkride, and maybe a few more.

Unfortunately, the pandemic kept a lot of pilots ground-bound for the better part of two years, so maintaining currency has assumed a new urgency. That goes double for instrument flying. Here’s hoping that all of us get back up to speed.That’s the letter of the law. The spirit of the law—the general consensus of how the letter of the law is interpreted—can be a little looser when it comes to the pilot community. Like so many other regulatory areas, this interpretation is left up to a pilot’s or instructor’s discretion. You can fly only the minimum tasks listed above. You can fly approaches to the same three airports in your local area on every IPC you take and meet the regulatory requirements. Or you can push the envelope and go to some distant, unfamiliar airports and practice holds on back courses, night circling approaches, and procedures that require a bit more foreign than those you’re most accustomed to, like diversions to an alternate you’ve never flown to before. Always fly your club’s glass-cockpit airplane? Then maybe push the envelope by trying an IPC in the fleet’s steam-gauge airplane. In short, to meet the true spirit of the law, an IPC ideally should have elements of a challenge—not just consist of a series of the usual tasks you’d fly around the “home ’drome.”

To help an IPC’s variety and boost its challenge, you can take advantage of a simulator-like advanced aviation training device, which can be used for credit for most of the tasks required for the IPC—except circling approaches and landings, and engine-out work in multiengine airplanes. Those must be demonstrated in an aircraft. Even so, AATDs are great for preparing for an IPC, and even better for practicing procedures at unfamiliar airports. For those lucky enough to have access to level C or D full flight simulators, all of the IPC tasks can be completed in them—even the landings.

Unfortunately, the pandemic kept a lot of pilots ground-bound for the better part of two years, so maintaining currency has assumed a new urgency. That goes double for instrument flying. Here’s hoping that all of us get back up to speed, and do it by going the extra mile or two during our IPCs.