Disastrous course of action

A Meridian lands on the wrong runway

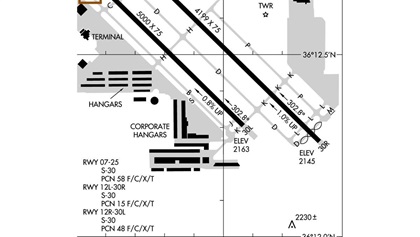

People knew them as a friendly couple, a chatty team in the cockpit, with her often working the radios when he flew the left seat of their Piper Malibu Meridian. Inbound from the north, they were cleared to land Runway 30L, flew overhead the field, and began a fast, swooping, left 240-degree descending turn to final.

Meanwhile, on Runway 30R, an instructor worked out a pilot in a Cessna 172, executing multiple touch-and-go landings, staying in a right pattern. The 172 requested and was cleared a short approach for 30R. Pilots report this as typical operations for VGT: local pattern work on Runway 30R with transient operations on the longer Runway 30L.

Based on ADS-B tracks, the high-wing Cessna turned from downwind and kept a steady right turn through base and on to final. The low-wing Piper continued its constant left turn through downwind, base, and onto final for Runway 30R. On three separate occasions, the tower controller cleared the Meridian to land 30L. After each transmission, the Meridian right seater acknowledged the landing clearance and repeated “…three-zero Left.” The airplanes collided on short final to Runway 30R; both occupants of each aircraft were killed.

The National Transportation Safety Board investigation is ongoing, but the preliminary report confirmed the converging ADS-B tracks. The accident looks to be a “wrong-surface event.” The Meridian lined up on the wrong runway despite repeated clearances and correct acknowledgements. The NTSB’s more difficult task will be in determining why. What factors led an experienced husband and wife team to line up on the wrong runway at their home field under typical operations?

We can sharpen our understanding of accidents and harvest our best lessons by assuming the pilots involved were skilled, competent, had no intention of a tragic outcome, and no recognition that one was brewing. Something in the environment or something in their cockpit made what we can now see as a disastrous course of action seem to be the most logical course of action to them at the time.

The Meridian couple was hailed by an acquaintance on tower frequency as they entered local operations. The voice—presumably that of another pilot—didn’t just transmit a quick hello, but attempted to engage in a dialogue, asking about their trip. Such extraneous communications violate protocol on a controlled frequency, but more importantly they distract pilots in the pattern, which is a critical phase of flight and where most of our midair collisions happen in general aviation. Such extraneous calls are a distraction to everyone on frequency and almost certainly aggravated the tower controller at North Las Vegas and distracted him. “Sterile cockpits,” which limit conversations below a certain altitude to items critical for takeoff and landing, are mandatory in professional flying. They are a good practice for us to adopt in GA when within 5 miles of a VFR pattern or starting an IFR approach. Did the breach in communications protocol distract the team in the Meridian just enough to cause a loss of focus, or a drop in situational awareness? Maybe. It certainly didn’t help.

Was there a disconnect between the team inside the cockpit of the Meridian? The right-seat radio operator knew the clearance was to the left runway, but did the pilot flying understand the assignment? A good practice is for a crew in any airplane to perform verbal challenge and response confirmation of landing runways. Even nonpilot passengers can perform this task.

Did the Meridian crew actually understand its position, over-shooting the left runway, and was it developing a plan but just didn’t call it yet? Anytime we deviate from controller direction, or known or expected procedures, we must call it as soon as we recognize it. And such calls are always “nonstandard.” We shouldn’t worry about the correct call or the right way to do it. We just need to speak—announce our deviation and our intention as clearly as we can.

Perhaps the couple, both of them, just completely misidentified the runways and lined up on 30R, believing they were on 30L. Parallel, offset runways are one of the highest-risk environments for wrong surface events. Something about them can create an illusion and lead to lining up on the wrong runway. Perhaps we glom on to the largest or most prominent runway; perhaps in a glance, we misidentify parallel taxiways as runways; sometimes, we get caught in expectation bias and land on our “typical” runway or the runway we were first cleared to. We can mitigate some of the risk of parallel, offset runways by knowing they present a high-threat environment for a wrong surface event and briefing their presence as part of our arrival procedure. Another good technique is to dial in an approach to the cleared runway, even if flying a VFR pattern.

Even under direction of a control tower, we must maintain our own situational awareness and continue vigilant see-and-avoid operations in the traffic pattern.The unusual pattern entry certainly didn’t help, despite having tower controllers working to assist in deconfliction. The accident scenario at North Las Vegas is exactly why the FAA discourages overhead, descending pattern entry. Long, extended turns to final like the Meridian used present a lengthy “belly-up” period when pilots are blind to conflicting traffic. In a nontowered environment, a standard pattern entry—extending out a couple miles, descending to pattern altitude and turning back to enter downwind from a 45 degree offset—offers longer and better visibility to detect conflicts. Anytime we engage in extended turns we will benefit from rolling out of the turn at least every 90 degrees to clear our flight path and check for traffic on our “belly-up” side.

And what about the Cessna 172? The pilots seemed to be executing everything correctly, and yet they lost their lives. It’s not casting blame to look in hindsight—while recognizing we have the clarity of hindsight—to ask if there is anything they could have done to recognize an impending calamity so that, perhaps, if we are ever faced with a similar circumstance, we can identify it and use the lessons we learn to avoid the same tragic fate. Their continuous turn in a high-wing aircraft would possibly have blocked their view of the Meridian descending upon them. A quick “belly check” may have helped. Were they building pattern situational awareness, a mental map of other traffic? Such a mental map is always important, but especially so during simultaneous operations to parallel runways.

Finally, the accident is a harsh reminder that we cannot completely rely on air traffic controllers for deconfliction. We always have the responsibility to see and avoid. Likely, the controller community is assessing this incident as pilots are, to understand what went wrong and why the controller couldn’t prevent the collision. His repeated calls confirming the landing runway are a possible indication that he saw something developing, something that didn’t seem quite right. His vantage point seemed to offer good visibility to see a pending conflict developing. If in fact he did sense it, a more blatant call, in plain language, directing actions or warning of pending traffic may have been helpful.

Among the many lessons already emerging from the North Las Vegas midair, a prominent one is that even under direction of a control tower, we must maintain our own situational awareness and continue vigilant see-and-avoid operations in the traffic pattern.