Opinion: Real-life breakdowns

Dealing with problems away from home base

You’re typically stuck somewhere you don’t want to be and at the mercy of strangers you don’t know whether to trust. It’s usually frustrating, frightening, and exasperating.From firsthand experience, I can tell you these events are emotionally charged. You’re typically stuck somewhere you don’t want to be and at the mercy of strangers you don’t know whether to trust. It’s usually frustrating, frightening, and exasperating. You just want to go home.

Can’t get engine started

A few years back, a Cirrus SR22 owner from Florida called my company’s SavvyBreakdown hotline on Thanksgiving Day. He’d just finished a business meeting in Tallahassee and had returned to the airport to fly home to Gulf Shores, Alabama—about 200 nautical miles—for Thanksgiving dinner with his family.

“When I turn the key to the start position, I can hear the starter motor turning,” he told our account manager Tom Cooper, the A&P/IA on call. “But the propeller just twitches a little and the engine won’t turn over.”

Cooper instantly recognized the symptoms of a slipping Continental starter drive adapter, the clutch-like device that couples the starter motor to the crankshaft during engine starting. He explained that the adapter contains a knurled steel drum that is geared to the crankshaft, and a beefy coiled spring that fits snugly over the drum and is driven by the starter motor. When the starter motor is energized, the spring grabs only the drum like a finger trap and cranks the engine. Once the engine starts, the spring relaxes its grip on the drum and disengages the starter motor from the crankshaft.

“If the outside of the drum or inside of the spring become worn, the starter drive adapter will slip and cause exactly the symptoms you have described,” Cooper explained.

The owner replied that there was a Cirrus Authorized Service Center on the field at Tallahassee, and he would try to have the SR22 towed there so they could work on replacing the starter drive adapter the following day. He was clearly upset that he would not be able to get home to Gulf Shores in time for Thanksgiving dinner.

Cooper told the owner he didn’t think that was the best plan. Continental starter drive adapters for the IO-550-N engine were backordered for at least four weeks, and once a replacement adapter was in hand it would probably take 12 hours of labor to remove the slipping adapter and install the new one.

“See if the FBO can bring over a 28-volt ground power unit,” said Cooper. “In our experience, a slipping Continental adapter is usually good for a few more starts if the airplane is powered from a 28-volt GPU rather than the 24-volt ship’s battery. Let’s see if we can get you home for dinner.”

The owner thought this was worth a shot and called the FBO. About 20 miutes later, he phoned Cooper again. “Tom, it worked! You’re a magician!” the owner said over the sound of the running engine.

“Good flight and enjoy the turkey,” Cooper replied. “I’ll contact your home service center in the morning and have them order a rebuilt starter adapter for you.” The owner agreed that he would be much more comfortable having the work done by his regular shop.Dead jug?

A Cessna owner called the hotline to say that one of his cylinders died in flight and he was grounded at a small unattended airstrip. When asked for more details, the owner reported that his JPI engine monitor had alarmed with a “DIFF” message, signifying that there was an abnormal spread between the hottest and coolest exhaust gas temperature. When the owner looked at the JPI display, the EGT bar for the number 3 cylinder had disappeared. He decided to make a precautionary landing.

A Cessna owner called the hotline to say that one of his cylinders died in flight and he was grounded at a small unattended airstrip. When asked for more details, the owner reported that his JPI engine monitor had alarmed with a “DIFF” message, signifying that there was an abnormal spread between the hottest and coolest exhaust gas temperature. When the owner looked at the JPI display, the EGT bar for the number 3 cylinder had disappeared. He decided to make a precautionary landing.

Our on-call account manager asked the owner a series of questions to determine whether this was a genuine cylinder issue or just an indication problem. Was the engine running rough? Did it lose power?

“Uh, no, I don’t recall feeling any roughness or power loss.”

“What was the cylinder head temperature indication for cylinder number 3?”

“Honestly, I didn’t notice. When I saw the missing EGT bar, I immediately thought ‘the fire has gone out’ and decided to get on the ground and sort things out there.”

This was sounding more and more like a simple indication problem—bad EGT probe, flakey connection, or the like—but our account manager wanted to make sure. He really wanted to get the captured engine monitor data, but that was going to be difficult under the circumstances.

“Now, here comes the fun part,” Cooper said, and instructed the pilot to whack the top of the balky contactor with a hammer or similar heavy object.“Could you go do a short engine runup and capture a video of the engine monitor display that I could look at?”

About 15 minutes later, the account manager received and reviewed the requested video. He observed that the CHT for cylinder number 3 was roughly the same as the other cylinders, and also noticed that the digital readout of the number 3 EGT was missing altogether and not just displaying some cool temperature.

“This is definitely an indication problem,” he told the owner. “Might be a bad EGT probe or a loose harness connection. In any case, it’s not a safety-of-flight issue, so I suggest you continue your trip and have the harness fixed or probe replaced when you get home or at the next convenient opportunity.”

The owner was relieved and continued his trip uneventfully.

Loss of oil

A Piper owner who called the hotline sounded panicked. “Shortly after takeoff, oil covered the windshield,” she said. “I reduced power and returned to the airport immediately and was able to land safely. When I shut down and got out, there was oil everywhere and I found the oil filler cap was loose.”

“Welcome to the club,” our on-call account manager said. “Quite a few of us have had that experience.”

“But when I checked the dipstick, I couldn’t see any oil there,” the owner said. “Is my engine toast? What should I do?”

“Don’t panic,” the account manager said. “There’s a good chance the engine is fine, but we need to check some things to be sure.”

Our account manager contacted the local A&P and asked him to cut open the oil filter and pull the suction screen. The A&P reported back that no significant metal was found in either place. Our account manager asked the A&P to install a new filter, service the sump with fresh oil, and clean up the oil mess as well as possible.

“You should be good to go,” the account manager told the owner, “But in an abundance of caution I suggest you have the oil filter inspected again in 10 hours or so. I’m confident you’ll find it clean.”

Gear won’t retract

A Cessna 340 owner had just taken off, but when he tried to retract the landing gear, nothing happened and all three green gear-down lights remained illuminated. He checked the landing gear circuit breakers and verified neither had tripped. He then returned to the small airport in the middle of nowhere and called the hotline.

“In my experience,” the account manager told the owner, “the most likely cause of such a non-retraction is a broken wire near the landing gear safety switch—the squat switch—on the left main landing gear, or possibly a failure of the squat switch itself.” He suggested the owner take a close look at the exposed wiring that runs to the squat switch.

“If you don’t see a problem with the wiring, I’d suggest you fly home with gear down and deal with the issue at your regular shop, or at least to an airport with a shop that knows twin Cessnas,” said the account manager. “There’s no law that requires you to retract the gear. Just make sure you don’t exceed the VLE speed—I believe it’s about 140 knots indicated—so you don’t damage the gear doors.”

The twin Cessna owner did find a broken squat switch wire and was able to make a temporary splice. He then took off and retracted the gear normally. He then flew home uneventfully and had his A&P make a proper repair to the wiring.

Cracked windshield

A Beechcraft Bonanza owner called to say that he’d gone out to his airplane and was shocked to find an eight-inch-long crack in the windshield. He asked our on-call account manager whether it would be safe to fly home that way.

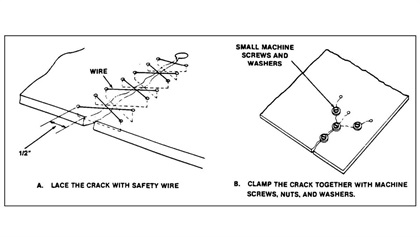

“At minimum, I’d recommend stop-drilling the end of the crack with an 1/8-inch diameter hole to prevent it from growing any further,” our account manager told the owner. “But for a crack as long as the one you describe, I would suggest reinforcing the crack using one of two FAA-approved temporary repair methods—I’ll send the details to your phone.”

The account manager sent the owner a drawing from Advisory Circular AC 43.13-1B Figure 3-24 illustrating the two approved temporary repair methods for cracked plastic windshields. One involves lacing up the crack with stainless steel wire, and the other clamps the crack together with small machine screws, nuts, and washers.

“They’re both ugly as hell,” the account manager warned, “but they’ll keep the cracked windshield intact until you’re able to have a new windshield installed once you get home. For your 8-inch crack, I suggest the wire-lacing repair method.”

Uncommanded cranking

A pilot flying a Cessna 172 owned by his local flying club called the hotline to report that when he turned on the airplane’s master switch, the starter immediately started cranking the engine. Startled, he turned the master switch off and called for help. It was a Sunday and there was no maintenance available on the field.

Tom Cooper was on call again that day, and he immediately diagnosed this as a classic case of a stuck/welded starter contactor (relay). Cooper explained that the proper fix would be to order and install a new contactor. “But there’s an old A&P trick that might get you home today,” Cooper said. “I can talk you through it if you’re game to try it.”

Tom Cooper was on call again that day, and he immediately diagnosed this as a classic case of a stuck/welded starter contactor (relay). Cooper explained that the proper fix would be to order and install a new contactor. “But there’s an old A&P trick that might get you home today,” Cooper said. “I can talk you through it if you’re game to try it.”

Cooper talked the pilot through removing the top engine cowling and locating the starter contactor mounted on the firewall. “Now, here comes the fun part,” Cooper said, and instructed the pilot to whack the top of the balky contactor with a hammer or similar heavy object.

“Are you sure?” asked the pilot, who didn’t see this one coming.

“Yup,” Cooper said, and explained that a sharp whack would usually free up the welded contacts inside the contactor.

The pilot dutifully whacked the contactor a few times, then at Cooper’s direction tried turning on the master switch. The starter didn’t engage. Cooper had him try turning the key to the “start” position and then releasing it. The starter engaged and disengaged normally. The pilot sounded amazed.

“This is only a temporary fix,” cautioned Cooper. “Make sure they replace the starter contactor ASAP once you get the airplane home.” The pilot acknowledged this, reinstalled the top cowling, and flew home without further incident.

Rules for dealing with breakdowns

These real-life case studies illustrate some of the important rules we use when dealing with breakdowns away from home base. Our first job is to gather information about the symptoms and try to arrive at a probable diagnosis. We then assess whether the issue represents a safety-of-flight hazard.

If it isn’t a safety-of-flight concern, we advise the owner or pilot that we think it’s OK to fly home and deal with the problem there. We try to avoid doing repairs away from home base whenever possible.

Of course, sometimes such repairs are unavoidable, in which case we recommend doing the minimum repairs necessary to make the airplane safe to fly home. Frequently that means doing a temporary “battlefield repair” or finding a workaround that allows the airplane to fly home safely where a “proper repair” can be made.

We’re always focused on solving the owner or pilot’s immediate problem (i.e., stuck somewhere they don’t want to be) rather than on fixing the airplane. We call this philosophy “owner first, airplane second.” I suggest you apply this approach next time you have a mechanical problem away from home. Mike Busch is an A&P/IA.