‘Green deck’

Panther Helicopters serves the Gulf of Mexico

It’s the sound of industry at work—and music to Lance Panepinto’s ears. He is the owner and founder of Panther Helicopters in Belle Chasse, Louisiana.

Offshore operations

Panepinto started Panther Helicopters in 1981 as an offshoot of his father Phil Panepinto’s seaplane business, Southern Seaplane Inc. (see “Fisherman’s Paradise,” November 2022 AOPA Pilot). The elder Panepinto had served the oil industry with his seaplanes since the late 1950s, but helicopters became the more viable mode of transportation for workers and others needing to fly out to the offshore oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico. Based in a suburb of New Orleans, the company was perfectly positioned for the job, and the younger Panepinto based his helicopter business down the street from his father’s operation (his father was not interested in expanding into helicopters).

The early 1980s was the height of oil and gas production in the United States. Offshore oil rigs have been in the Gulf of Mexico since as early as 1938 when Pure Oil (now Chevron) and Superior (now ExxonMobil) erected a platform a mile offshore of Calcasieu Parish in Louisiana. From 1954 to 2007, federal offshore areas produced 16.8 billion barrels of oil and 173 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. In 2007, federal offshore sites produced 27 percent of the oil and 14 percent of the natural gas in the U.S., according to U.S. Minerals Management Services. An executive order by then-President George H.W. Bush banned offshore drilling in 1990. That was reversed in 2008 by President George Bush, but in 2010, the largest offshore oil spill occurred in the Gulf of Mexico. The Deepwater Horizon oil spill is regarded as one of the worst environmental disasters in history.

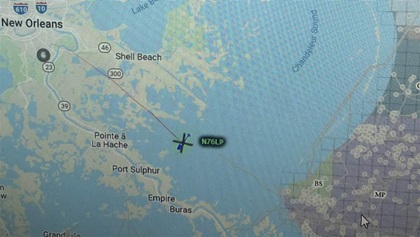

“Flying offshore is a unique experience,” says Panepinto, who has weathered the ups and downs and political discourse of the industry for nearly 45 years. He started Panther with a Robinson R22 flying as PIC in all of the weather scenarios that the volatile Gulf can stir up. He made his mark by undertaking what he calls “flying in the Perfect Storm.” He took on missions to fly to the ships at the mouth of the river. “That’s the most dangerous flying—flying at night in the fog trying to find the ships that are moving. It’s nothing to play with; I’m glad I don’t have to do that anymore.” But it got his name out and the smaller, independent oil companies started calling. Panther flies as far as 120 miles offshore to smaller, independent oil company rigs and also now delivers pipeline workers to the larger platforms.

The challenge of landing on an oil rig platform is great. “There is no windsock on the platform. You read the water, checking the wave movement. We call 10 minutes out so the activity on the heliport is shut down and ready for us. Then you get the ‘green deck’ permit to land from the production foreman. There could be many reasons you can’t land—there could be a crane on the deck, a boat in the area, or people or other refueling operations. And then there’s methane gas. All operations stop.” The gas is invisible and if a helicopter flies through it, there is the potential for an explosion. The helipads range from 35 feet by 35 feet to 50 feet by 50 feet.

Risky flying

Panther Helicopters now has four Bell 206 L4s, two 407s, and a JetRanger. “I really appreciate the Bell product,” he says. “The 206 was really the first to fly in the Gulf. It’s proven, the product support is there, and it’s a durable product.” The aircraft are not IFR-certified even though his pilots are. “The birds are IFR capable but not certified. I wanted it that way so in case they get caught in weather for safety, but we fly day and night VFR only.”

Panepinto calls this type of flying “risky” and says all pilots in his employ have water egress training (see “‘Need to Escape,’” November 2022 AOPA Pilot). “Flying helicopters here is challenging; I like challenges.” He owns a Cessna 185 on floats when he wants it “easy and relaxing,” he says.

“A pilot who wants to work for me has an instrument rating, 500 helicopter hours, and then 250 hours in make and model; that gets them to 750 hours. Those with offshore experience are the most valuable to me. Right now, there is a demand for pilots and mechanics; I try to make sure this is a good environment, and the benefits are good.”

His pilots fly “14 and 14,” which is two weeks of flying and two weeks off. This is standard across the Gulf. Most of his pilots have more than 3,000 hours and lots of experience flying in the Gulf.

“The Gulf is the second worst area to fly in the U.S.,” he says. If you’re wondering, Seattle is first. Louisiana gets the fog from cooling water and warm fronts. “The sea fog can get so thick you can’t see the rim of the helipad. You have to wait until the wind blows it away. You have to teach a new guy that he can land on a perfectly clear day, go inside, and eat lunch at the cafeteria on the platform and come out and not be able to leave.”

His helicopters have wind limits—above 35 mph, the pilot can’t shut the blades down or the wind will “knock the back end off; if we’re picking up a guy on a rig, we’ll keep the bird running waiting for him.” These are his rules, he says, “Panther rules.”

All in the family

The company has 10 pilots on staff and has another division within the company that provides helicopter maintenance. Lance Panepinto Jr., the younger of the owner’s sons, is his father’s righthand man, contributing skills in paint, body work, and refueling. “I’m right there next to Dad,” he says.

“He has become a jack of all trades,” his father says.

“Dad really likes things to be pristine, especially the painting,” says his son.

The signature colors of the company are pink and black, colors his wife picked out when they first started the company. Paula is his high school sweetheart, and one of their first dates was in an airplane. “I wanted the birds to be on a VIP level; the pink and black is first class—it has pizazz. They are impressive.”

Most of the Panepinto family is in aviation, from his older brother and niece at Southern Seaplane to his middle brother Lane in aviation maintenance. His older son Paul worked in the business to put himself through college and is now a public-school principal. “My older brother Lyle has the legacy that my dad started. My brother Lane is a first-class mechanic. Our whole family is in aviation and for all of our lives. It’s a good world.”

“Being a part of a family business is great,” adds his son Lance. “We’re all in this business together.”

“That’s what we do; we’re aviators,” says his father.

The Gulf of Mexico is home to more than 4,000 abandoned oil rigs. Many of these oil rigs were abandoned between the late 1970s and early 1990s when oil prices plummeted below $10 per barrel and the offshore drilling industry went into decline. Most of these rigs were left to rust and fall apart. The oil rigs have become natural reefs, popular with fishermen. —maritimepage.com

The Gulf of Mexico is home to more than 4,000 abandoned oil rigs. Many of these oil rigs were abandoned between the late 1970s and early 1990s when oil prices plummeted below $10 per barrel and the offshore drilling industry went into decline. Most of these rigs were left to rust and fall apart. The oil rigs have become natural reefs, popular with fishermen. —maritimepage.com