Collected on the approach

Set the stage for a great landing every time

And the local Piggly Wiggly just doesn’t cut it for a vegetarian like me. So, when I first moved to Sewanee, Tennessee, I made a weekly 160-mile round-trip slog to Nashville in search of better options. Several years later, I earned my pilot certificate and along with it with it, I had hoped, an end to those grueling drives.

With a temporary certificate tucked in my wallet, I pointed te of my airplane toward Nashville and smiled as I sailed past cars on I-24. No longer would that be me! Of course, the shopping part still wouldn’t be fun, but sandwiching that chore between two flights made the entire enterprise more than palatable—I was actually excited to go.

Nashville Approach handed me off to the tower and, as I neared Nashville Airport (BNA), the controller requested my “maximum forward speed.” It’s as if he saw my aircraft type on his screen and just knew the kind of approach I was planning. And he was right.

Touching down at minimal airspeed is imperative on every landing and my instructor taught me how to achieve that in the Cessna 152: abeam the numbers on the downwind leg, retard the throttle to 1,600 rpm, extend 20 degrees of flaps, hold te level with the horizon until the airspeed indicator shows 60 knots. Trim for hands-off flight at that airspeed throughout the rest of the pattern. Continually reduce the throttle and close it when the runway is made. Arriving at the flare with a low airspeed means touching down with minimal energy to dissipate. A stabilized approach with a constant airspeed will set the stage for a great landing every time. But is it really necessary?

Aviation author and flight instructor Rick Durden doesn’t think so. In fact, in “Landings: Watching the Really Good Pilots” (The Thinking Pilot’s Flight Manual: or, How to Survive Flying Little Airplanes and Have a Ball Doing It, Vol. 2), he scoffs at the idea. Durden explains that for “piston-engine airplanes, it’s just plain foolish to fly a three-mile final at 1.3 VS0; the pilot will be a year older before getting to the runway.” Furthermore, he says that the word stabilized applies only to jet airplanes that are flown with gear and flaps down at a higher power setting on final approach since those engines take so long to spool up in a go-around scenario.

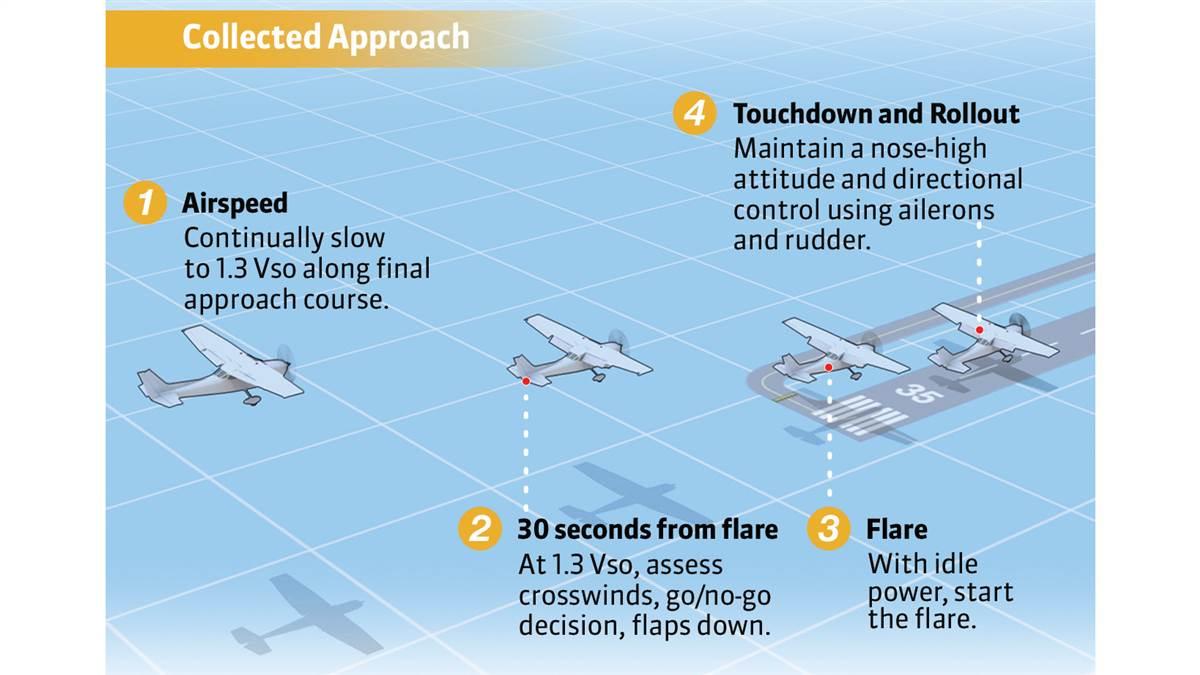

So, if not stabilized then, how should a piston-engine pilot guide her airplane around the pattern? Durden borrows a term from auto racing in which a driver has the car collected as she enters a turn. “An open-wheel racer may be going anywhere from 200 to 240 mph as it enters a turn at Indy. Depending on conditions, the driver may or may not be using the brakes to set up for the turn, may or may not have to make a gear change and may or may not have a choice of ‘lines’ through the turn.” When the driver has made all the appropriate decisions and is ready to act on them, the driver has the car collected. Durden continues, “It’s a perfect term for that last bit of the final approach before the throttle is closed and the flare begins.”

In his article, Durden emphasizes the need to touch down with minimal energy but emphasizes that just a half minute on speed before the flare is enough time for pilots to assess the wind conditions and tee up a great landing. “Being collected may still mean a final approach that is flown at a constantly decreasing speed to target a desired speed at flare height.”

That Durden concentrates on time in the pattern rather than distance makes a lot of sense. When I have flown with a strong wind straight down the runway, it’s sometimes been clear that I could have turned on the base leg much sooner. In fact, a greater distance on the final approach segment in that case will even make it less likely to reach the runway if the engine fails.

I confess that I still fly my trusty 60-knot approach around the patch at my home airport when the pattern is quiet. But if I expect to land at busy airports without annoying controllers too badly in the process, then mastering this advanced technique is a must. Being collected may mean flying a continually decreasing airspeed to target a minimal speed at the flare, but it takes practice to learn how to adjust power and stick pressure to ensure a consistent result. If you don’t regularly practice this yourself, try including it on your next flight review.

Winter is my favorite time to catch up on reading, and one cold, rainy day, I reached for a dog-eared copy of Durden’s book that sits on my bookshelf next to Wolfgang Langewiesche’s Stick and Rudder. His piece on landings brought back memories of my first flight to Nashville in which I smoothly transitioned from 90 knots on most of the approach to 60 knots at the beginning of the runway. Learning to fly a collected approach has been key to regular, $100 veggie burger runs and so many cherished adventures over the years.