Know thy airplane

Short circuit makes for a long day

By Kevin Knight

It was a perfect day for flying 70 miles north of Seattle to Orcas Island. My wife and I were flying to a friend’s birthday party in a 1983 Cessna TR182 with retractable landing gear.

I hadn’t logged much time in the airplane, but a flight to the Mexican border months earlier went flawlessly and confirmed the aircraft was flying book speeds, consuming expected amounts of fuel, and had no bad habits. So far, so good.

Still, paranoia about the hydraulic landing gear haunted me. I’d read about issues with the landing gear, which weren’t surprising after watching a 182RG deploy and retract its gear. It reminded me of a praying mantis, particularly during takeoff. The spindly rear legs dangle behind the fuselage before folding themselves within.

Unlike most other light airplanes with retractable gear, Cessna engineers decided to create a hybrid system requiring a power pack generating 1,500 psi of hydraulic pressure through various lines and valves. If there’s an electrical issue, you have to hand pump the gear down. If there’s a hydraulic leak, you’ll be landing on the belly. If the motor powering the pressure pack doesn’t automatically turn itself off when reaching the correct pressure, it will essentially burn itself up. Mechanics and other RG pilots advised that if I heard the pump running continuously, I should pull the breaker. I thus had my mechanic add a small, yellow light bulb to the panel. It shone brightly when the pump was running. If it stayed on more than 10 seconds after the gear was down or up, I would pull the designated gear pump breaker.

We departed and quickly climbed to 3,500 feet. We heard the reassuring thump of the landing gear coming up, so I focused on engine management and talking with Seattle Center. I set the propeller and manifold pressure for a fuel burn of 10 gph and leisurely speed of 126 knots. However, indicated airspeed showed a true airspeed of 110 knots. What’s going on? I wondered.

“We are way below book speed,” I told my wife. “Do you see the landing gear?”

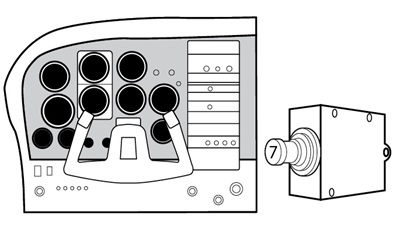

She looked at the mirror on the wing and said the gear was trailing next to the fuselage. I told Seattle Center we needed to work the problem and would be in a holding pattern. Going through the emergency procedures, I saw the circuit breaker for the gear pump had popped out. I pushed it in, recycled the gear, and landed uneventfully. After returning home that evening, I contacted several A&Ps. The consensus was I had a bad circuit breaker.

That made sense, except every breaker had been replaced just a few months earlier. What was going on? I reviewed closeup photos of my original panel and noticed the amperage numbers painted on the faces of most circuit breakers were worn off. I then pulled the electrical schematics and called Cessna to confirm the correct breaker rating for the gear pump. It’s 35 amps, yet the avionics shop had installed a 20-amp breaker.

The airplane easily passed its annual after the avionics upgrade. Apparently, retracting and deploying the landing gear while the airplane was on jacks didn’t replicate the effect gravity and fast-moving air impose during takeoff.

The lessons I learned are to thoroughly know your airplane’s systems, remain cool and work a problem when one develops, don’t skimp on maintenance, and never assume a shop or technician won’t make mistakes.