Time passages

Jimmy Doolittle’s watch still tells a story

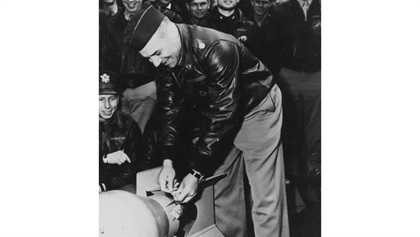

It’s Gen. James “Jimmy” Doolittle’s personal watch, the one he was wearing on the legendary Tokyo Raid, and its ticking feels louder than the twin 1,700-horsepower engines.

Aviators know how big a debt we owe to Doolittle’s leadership and innovation. A sample of his storied career includes speed records, the development of high-octane fuel and instrument flying equipment, earning the first Ph.D. in aeronautics awarded by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, commanding the U.S. 8th Air Force, and the only American to receive both the Medal of Honor and the Presidential Medal of Freedom. It makes perfect sense that such a noteworthy figure should also have a watch of high significance in aviation.

At first glance, the watch looks unassuming. Unlike the ornate and high-tech pilot watches of today, this boasts a practical face, tasteful leather band, and no Wi-Fi connection. On the back is etched the words “Invented by Col. Chas. A. Lindbergh,” the company name and patent number, and another added phrase squeezed in: “Jim from mother 1939.”

First produced by Longines in 1931, these “angle hour” watches were personally designed by Lindbergh to aid pilots in aerial navigation—in addition to telling time, it can determine precise geographical coordinates (see “Move Over, Garmin” right). Because of this, angle hour watches were a natural choice for Doolittle’s most famous undertaking, the Tokyo Raid, which required hundreds of miles of flight over water and hostile territory with limited fuel.

Also known as the Doolittle Raid, the mission set in motion events that would bring about the fall of Japanese rule in the Pacific (see “The ‘Raid’”). Eighty handpicked crewmembers, including Doolittle as their leader, underwent strenuous training in short-field operations, navigation, and very low-level flight for this high-risk and skill-demanding mission. Although the raid only inflicted a small amount of physical damage, its main objective was a success—it shook the Japanese public’s faith in their warlords and gave Americans at their lowest point a desperately needed boost of courage.

This watch’s journey began with Doolittle and his friend of many years, Don Penny—Hollywood writer, comedian, and actor known for such productions as 12 O’Clock High—who worked in communications for the Gerald R. Ford administration. Although the Smithsonian requested the watch, Doolittle didn’t want it to go to a museum, worried that “They’ll just put it in a box, and nobody’ll ever see it.” Penny collected fine watches, and in 1992 Doolittle passed on the Raider watch to Penny with a solemn injunction: “Use this to keep the memory of my boys alive.”

Two decades later, Penny discovered that the B–25 Panchito was in his vicinity offering rides with Dick Cole, Doolittle’s co-pilot on the raid. When he went out to meet them, Cole recognized Penny’s watch immediately. One of the Panchito staff heard their ensuing conversation and pulled Penny out to the B–25, where pilot Larry Kelley was briefing passengers.

Kelley has been involved with the Doolittle Raiders for decades and is the executive director of the Delaware Aviation Museum Foundation, home of Panchito. Named an “Honorary Doolittle Raider” by the survivors, he has been instrumental in keeping their story alive and honored in many ways. As Penny began to attend Raider events Kelley was involved in, he saw that this crew was doing what he himself had been charged with, and eventually passed the watch to Kelley, deciding he was the right person to carry the torch. Kelley takes the responsibility seriously.

“The watch does not belong to Larry Kelley. It’s an artifact, it belongs to history,” he said. “I’m just a caretaker...a person that happens to have a safety deposit box this thing resides in. Post your stories about what the watch stands for and what the Raiders did, how they changed the course of the war in the Pacific. Tell that story—one of the few artifacts to come from one of the greatest airmen that ever flew an airplane.”

Tell the story it does. Seeing the watch takes your breath away—not just in awe, but with the weight of meaning—and its soft ticking conveys the spirit of Doolittle and his boys more profoundly than any person could.

On April 18, 1942, 16 stripped-down B–25s with extra fuel tanks were crammed onto the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Hornet. The first aircraft, flown by Doolittle and his crew, had only 467 feet to take off, followed by the others. They flew 650 miles over water to attack Tokyo and other main cities, dropping bombs from as low as 1,200 feet and continuing to China where they ditched, bailed out, or crash-landed (one diverted to the Soviet Union). Of the 80 crewmembers, three were killed in action, three executed by the Japanese, and one died in captivity. In 2014 the group received the Congressional Gold Medal for “outstanding heroism, valor, skill, and service to the United States.”

On April 18, 1942, 16 stripped-down B–25s with extra fuel tanks were crammed onto the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Hornet. The first aircraft, flown by Doolittle and his crew, had only 467 feet to take off, followed by the others. They flew 650 miles over water to attack Tokyo and other main cities, dropping bombs from as low as 1,200 feet and continuing to China where they ditched, bailed out, or crash-landed (one diverted to the Soviet Union). Of the 80 crewmembers, three were killed in action, three executed by the Japanese, and one died in captivity. In 2014 the group received the Congressional Gold Medal for “outstanding heroism, valor, skill, and service to the United States.” Coming in variations of appearance and size over its production life, the Lindbergh Hour Angle watch was a fantastic navigation aid. With a little mental math, a sextant, a radio, and an air almanac (which lists the geographical position of celestial bodies at certain dates), a pilot or navigator could calculate the coordinates of their location in the following steps:

Coming in variations of appearance and size over its production life, the Lindbergh Hour Angle watch was a fantastic navigation aid. With a little mental math, a sextant, a radio, and an air almanac (which lists the geographical position of celestial bodies at certain dates), a pilot or navigator could calculate the coordinates of their location in the following steps: