Between the maneuvers

Taking command of your aircraft

As an examiner, though, I’d say much of my critique and advice refers more generally to aircraft control. Time spent during the practical exam is meant to demonstrate that the candidate deserves the added privilege the certificate or rating affords. The airmen certification standards (ACS) merely ensure that we see the pilot fly through a range of flight phases and scenarios and the flight portion begins from preflight until the aircraft is shut down and secured.

Here is some of the general advice I find myself giving on many practical exams.

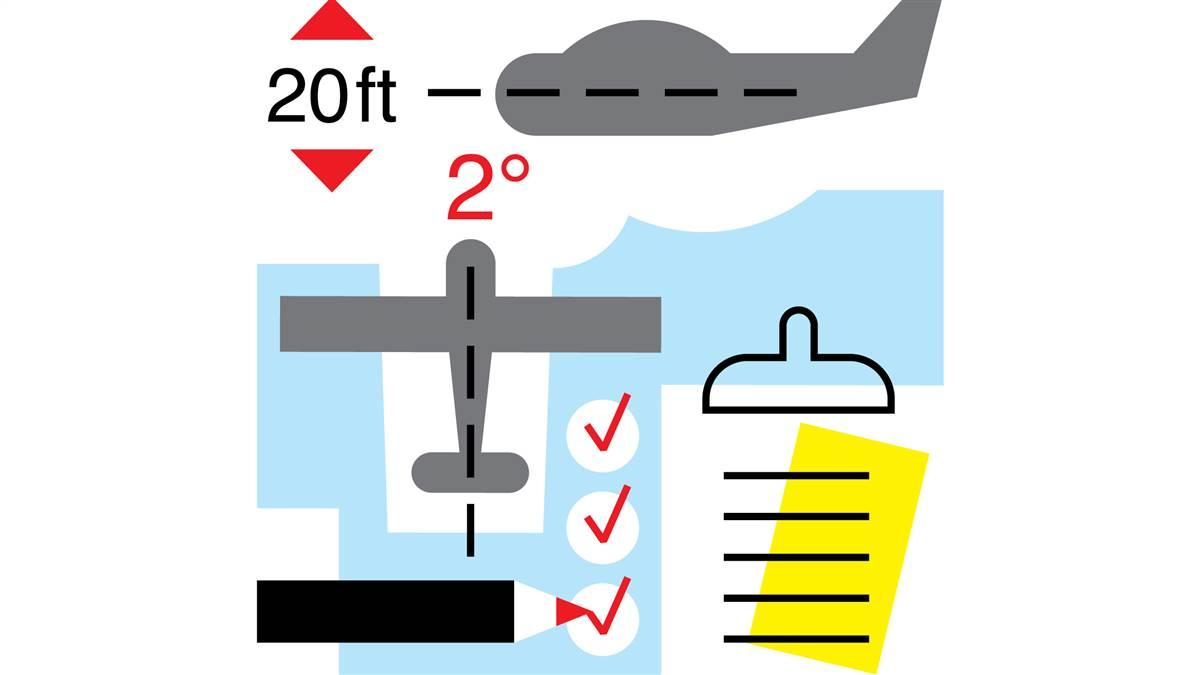

Fly with precision.

The ACS provide minimum standards and pilots should always strive for far higher ones. While, say, deviating up and down 100 feet and wandering 10 degrees off assigned heading may be allowed, such excursions don’t instill confidence in the examiner and certainly won’t with passengers. Aim to stay within 20 feet of altitude and 2 degrees of heading. It’s easier to catch deviations and, even on a bad day, you’ll fly well within ACS standards.

Clear the area.

No, I don’t mean the type of clearing turns that candidates introduce with fanfare. I often witness a pilot announce that he will make a 90-degree clearing turn to the left, followed by a 90-degree turn back to the right but then not even look left before commencing the clearing turn. That tells me he’s missed the point of the clearing turn. Pilots should always be aware of their surroundings and look around before making the aircraft change direction. My heart sinks when a candidate asks, “Would you like me to clear the area again?” before entering a subsequent maneuver. My typical response is, “Well, if you are sure the area is clear then no need; otherwise, you should clear the area.” And clearing the area on the ground is just as important. Always remember to yell, “Clear prop!” before hitting the starter and continue to look outside when the propeller is turning.

Use checklists.

The FAA stresses that we evaluate checklist use and with good reason. How many senseless accidents do we see each year that could have been prevented by following one? The structure of a good checklist and a way to use it effectively varies from pilot to pilot so it’s imperative to find one that feels right to you—detailed enough to hit all the important points but simple enough so that you don’t get bogged down in it. I’ve always found it helpful to design my own checklists especially since, with equipment and panel upgrades, the one in my pilot’s operating handbook doesn’t cover many of the important items. In making or updating mine, I sit in my airplane and create flows to those items by memory and use the checklist to verify their completion.

Have a plan for approaching an airport.

Plugging the airport in the GPS navigator might be a good start but a more detailed plan should follow. For a nontowered field, calling up the local AWOS can give a sense for which runway might be in use as well as listening to the traffic announcing on the CTAF. And when you hear pilots announce on the radio, stop talking so you can hear those who are operating near or in the pattern and build a mental picture of the traffic flow. Do not descend to pattern altitude and head directly for the airport. I’ve seen candidates disrupt operations this way. Instead, start navigating toward a point near the airport for which a 45-degree entry to the downwind can be made. For example, if the winds at Franklin County Airport (UOS) are favoring Runway 7, I plan to arrive at pattern altitude, about two or three miles to the north. Any flight above the airport but not in the pattern should be done at least 500 feet above pattern altitude.

Fly a perfect pattern every time.

Know how the lower-level and surface winds are flowing to anticipate the corrections necessary to fly a rectangular pattern. For example, if the winds are from the northwest, crabbing to the right on the downwind will be important so the aircraft isn’t pushed too close to the runway. It may even make sense to fly a slightly wider downwind since the base leg, with a direct tailwind, will happen fast and overshooting final will happen if you’re not careful. The final approach segment will require either a crab or slip to the left to maintain the extended centerline. Be sure to roll out exactly onto an extended centerline as maintaining it provides valuable information for the touchdown. While crabbing or slipping (to the left in this case) are each fine techniques, I prefer the latter as I am constantly gauging how much aileron and rudder pressure is necessary. The aircraft should be in a slip when the upwind main tire meets the runway.

Take control of the airplane.

Especially on days with gusty winds, I get the impression that some candidates are merely along for the ride as airspeeds and altitudes vary more than they should. As an aircraft slows to near stalling speed, which should happen on every landing, controls are less effective, so more extreme deflections are necessary. Unfortunately, when the ground is nearby, this is exactly when pilots become too shy with them. I coach candidates of all levels, private through flight instructor, “Take control of this airplane and make it do what you need it to do.” Touching down with the upwind main wheel first, just off the runway centerline, with no side drift and the nose pointing exactly down the runway centerline can happen every time.

It’s easy to get caught up worrying about the ACS tolerances but remember that the examiner wants to see that you are a knowledgeable, safe, and skilled pilot who deserves new privileges. Demonstrate that and good results tend to follow.