Go-around went badly wrong

NTSB reports evidence of Stationair stall-spin in fatal Alaska accident

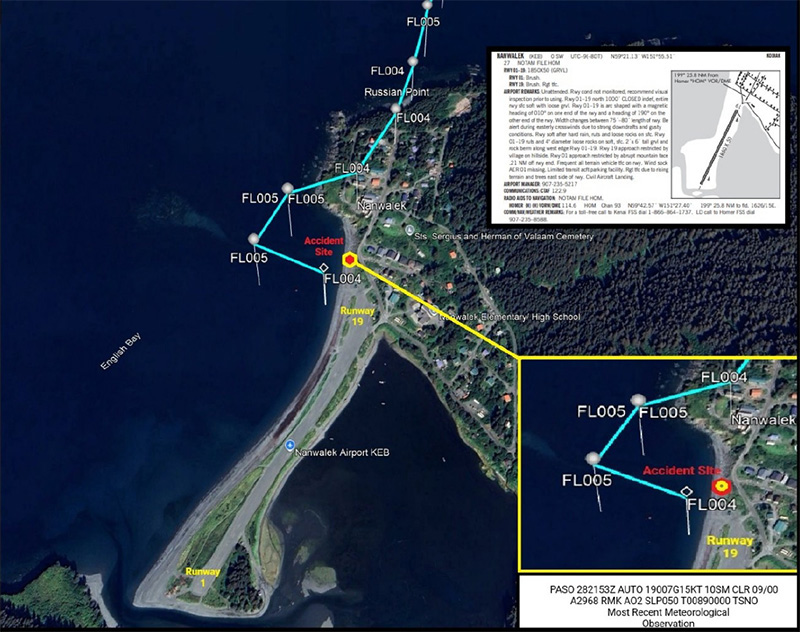

A Cessna T207 Turbo Stationair was destroyed April 28 attempting to land at Nanwalek Airport in Alaska, and the NTSB preliminary report includes details that point to loss of control during a go-around attempt.

The accident at 1:55 p.m. Alaska Daylight Time killed pilot Daniel Bunker, 48, and passenger Jenny Irene Miller, 37, and seriously injured a third passenger, whom authorities have not identified. It was the aircraft's fourth trip of the day, according to available ADS-B data, a Part 135 scheduled commuter flight between Homer, Alaska, and Nanwalek—about 20 nautical miles away—operated by Smokey Bay Air.

Another pilot approaching the same airport a few miles behind the accident aircraft told investigators that Bunker had reported a go-around on the radio: "there's something on the runway." Some witnesses reported seeing a dog on the runway as the airplane was on final approach.

FAA records show Bunker held a commercial pilot certificate with single-engine, multiengine, seaplane, and instrument ratings, and a second class medical issued in June with a corrective lens requirement.

The Stationair had departed Homer with 40 gallons of fuel on board, 271 pounds of passenger baggage, and 257 pounds of mail, the report notes, details that suggest the aircraft was hundreds of pounds below its maximum gross weight. Investigators found no signs of pre-impact flight control defect or damage, the propeller blades had "rotational signatures" (evidence the engine was producing power), and the flap selector was in the full-down position.

The aircraft was about 100 feet above the ground when the final ADS-B data point was captured. The aircraft sidestepped to the right of the runway while still over the village, the data show, and a witness stated the airplane increased throttle before entering the left bank that preceded the spiral into the ground.

While the precise timing of the events is unclear from the preliminary report, the sequence—sidestep, throttle increase, bank, spiral—suggests the pilot applied power while maneuvering close to the ground with full flaps in an aircraft that, while not close to maximum weight, was still carrying more than 1,200 pounds of people, fuel, baggage, and mail. That would put the wings at a higher angle of attack during approach, reducing the margin for error. As former AOPA Air Safety Institute leader (and former NTSB Vice Chairman) Bruce Landsberg wrote in this article about go-around technique, the application of power brings torque and a strong left-turning tendency, demanding prompt rudder correction.

Landsberg wrote that pitch control is also critical during a go-around, the goal being to arrest the descent but give the aircraft time to accelerate in level flight before climbing.

"In many aircraft you'll need to hold the nose level with forward pressure to keep the airplane from attaining too high an angle of attack as power is added," Landsberg wrote. "That's another tricky thing about go-arounds—we want to go up but have to hold the nose down. A strong left arm is an essential part of a successful go-around."

Landsberg wrote that the sequence—power, pitch, reduce (but don't fully retract) flaps, and retrim—requires more authoritative use of flight controls than pilots might suspect. "Want to see what it's like with full power, full flaps, and landing speed? Try a go-around at altitude. The control pressures may be surprisingly strong."