Waiting for spring

The volatile season has begun

The first few days of March this year gave us a good look at what we can expect from angry spring weather systems.

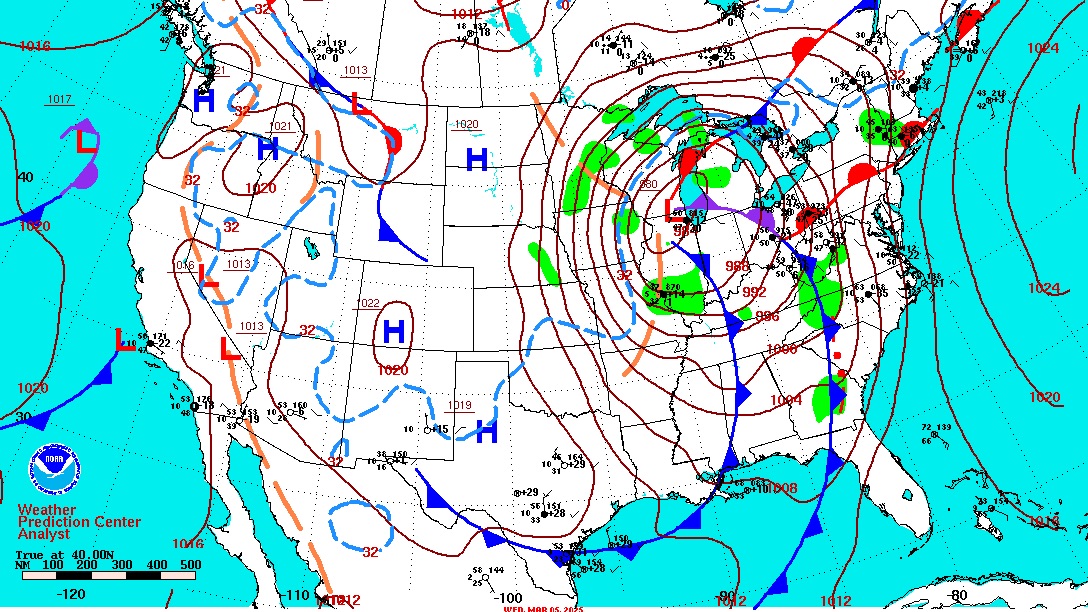

The situation on March 5 clearly shows the setup. Cold air from Alaska and Canada had been steadily flowing into the western half of the United States for several weeks. Meanwhile, warm winds from the Gulf of Mexico traveled northward into the central states. Now there was a cold half and a warmer half of the nation. That clash helped form a center of deep low pressure over the upper Midwest, trailing a strong cold front extending from the Great Lakes to the Gulf.

The result was blizzard conditions (defined as blowing or falling snow, winds of at least 35 mph, and visibility of a quarter-mile or less—all of these lasting at least three hours) over Minnesota and Wisconsin. Meanwhile, a pair of cold fronts formed an arc from Michigan to Florida. The lead cold front was a narrow band of clouds containing heavy rain; a tornado watch over the Carolinas, Georgia, and northern Florida; and a Storm Prediction Center mesoscale discussion threatening severe thunderstorms over the Mid-Atlantic states. G-airmets featured instrument weather conditions, strong surface winds, and low-level wind shear all along the eastern states.

Cloud tops? As high as FL210 over the low’s center, and as high as FL370 to FL450 within the cold front. Icing was advertised anywhere from 3,000 to FL190 near the low-pressure center, and from 6,000 feet to FL200 within the cold front’s clouds. And within that band of clouds, up at 30,000 feet, winds aloft were ranging from 70 to 100-plus knots out of the southwest and backing to the southeast. Backing winds turn counter-clockwise with altitude, and it’s this motion that imparts enough vorticity—or “spin”—at lower altitudes to create tornadoes. Hence the tornado watch boxes.

Anyone up for a cross-country? Unless you happen to have a turbine-powered airplane the best idea might be to park yourself in front of the TV, call up The Weather Channel, and wait it out. It’s March 5 as I write this, and the forecast is for the entire system to exit over the Atlantic in a day or two. The last METAR at nearby Dulles International Airport (IAD) posted winds out of 140 at 19 gusting to 29 knots, and a PC-24 that just departed IAD gave a pirep for moderate turbulence from 4,000 feet to FL200. My home anemometer just peaked at 30 mph out of the southeast, and the temperature just began its fall from 57 degrees Fahrenheit. The cold frontal passage should come by midday. It could be a doozy. That’s why I thought I’d stay put and crank out this case study. Take a look at the accompanying charts to see what March 5 had in store.

Thomas A. Horne is a former editor at large for AOPA media and the author of Flying America’s Weather.