Pioneering Pilatus

The sophisticated STOL jet

We are high over southern Wyoming, moving along at 420 KTAS (Mach 0.73), when Brian Mead, a Pilatus demonstration pilot at the Swiss company’s U.S. facility in nearby Broomfield, Colorado, clicks off the autopilot.

“The wing on this airplane is the key to its versatility,” says the former U.S. Air Force B–1 Lancer pilot, as he smoothly rolls into a 45-degree right bank and the pressure of 1.5 Gs pulls us firmly into our seats. “You can see how the airplane maintains its energy, and the wing is nowhere near its critical angle of attack.”

He turns over the controls to me and I leave the thrust levers for both Williams FJ44-4A-QPM turbofan FADEC engines in their maximum continuous power setting. Then I roll into a left turn and, focusing on the primary flight display, try to hold the green “meatball” on the white horizon line through 360 degrees of turn. Surprisingly, the airplane feels about as stable and well balanced at high altitude as it did during the takeoff and initial climb, so our altitude barely changes.

He turns over the controls to me and I leave the thrust levers for both Williams FJ44-4A-QPM turbofan FADEC engines in their maximum continuous power setting. Then I roll into a left turn and, focusing on the primary flight display, try to hold the green “meatball” on the white horizon line through 360 degrees of turn. Surprisingly, the airplane feels about as stable and well balanced at high altitude as it did during the takeoff and initial climb, so our altitude barely changes.

Mead picks up a descent clearance from Denver Center and, using the Honeywell Apex system’s track ball, programs a vertical path to follow. I pull back the power levers and follow the guidance while the 17,500-pound jet’s indicated airspeed creeps upward toward its maximum Mach number or MMO.

The PC–24 has two speed brake settings: half and full. I deploy them halfway expecting a telltale rumble that usually serves as a confession that the crew has done a poor job of descent management—yet airflow over the wings remains smooth. I extend the speed brakes fully and there’s a minor rumble that’s soon masked by light to moderate chop over the Rockies as we get closer to our mountain destination.

The weather at Steamboat Springs/Bob Adams Field (SBS) seems benign: clear skies, light and variable wind, and an air temperature of 70 degrees Fahrenheit. Yet the warmth and lack of a headwind increase landing and takeoff distances for the PC–24 on the 4,400-foot runway at a 6,882-foot elevation.

Mead plugs the numbers into the flight management computer and it calculates a 98-knot reference speed and a 3,000-foot balanced field length. Those figures seem impossibly low for a mid-sized jet, but they’re accurate. PC–24 reference speeds are typically between 95 and 99 knots, so we’re at the higher end of the range.

“Even so, we should be stopped around mid-field with hard braking,” Mead says. “Not many jets come to this airport, but it’s well within the PC–24’s capabilities.”

Tumultuous times

These should be boom times for Pilatus in the United States. The company’s PC–12 turboprop logged more flight time in 2024 than any other U.S. business aircraft in the airplane’s largest single market, and PC–24 sales and deliveries are near record levels in the United States and internationally.

The Colorado completions center delivered 90 new aircraft in 2024, and it’s in the process of expanding its facility and adding to its current 200-employee staff. Pilatus also intends to build an even larger facility for up to 300 employees in Sarasota, Florida.

The recent imposition of steep U.S. tariffs on international imports, however, is clouding the private company’s outlook. No one can say with certainty how high U.S. tariffs on Swiss imports will be, but the current number including surcharges for aluminum put the figure at more than 30 percent. Components such as engines and avionics manufactured in the United States are theoretically exempt from tariffs, but hard numbers are elusive.

Unforeseen tariffs are a huge unknown for Pilatus, a staid organization founded in 1939 whose hallmark is conservative, long-term planning. The company said it hasn’t altered any of its bullish plans for U.S. growth based on tariffs.

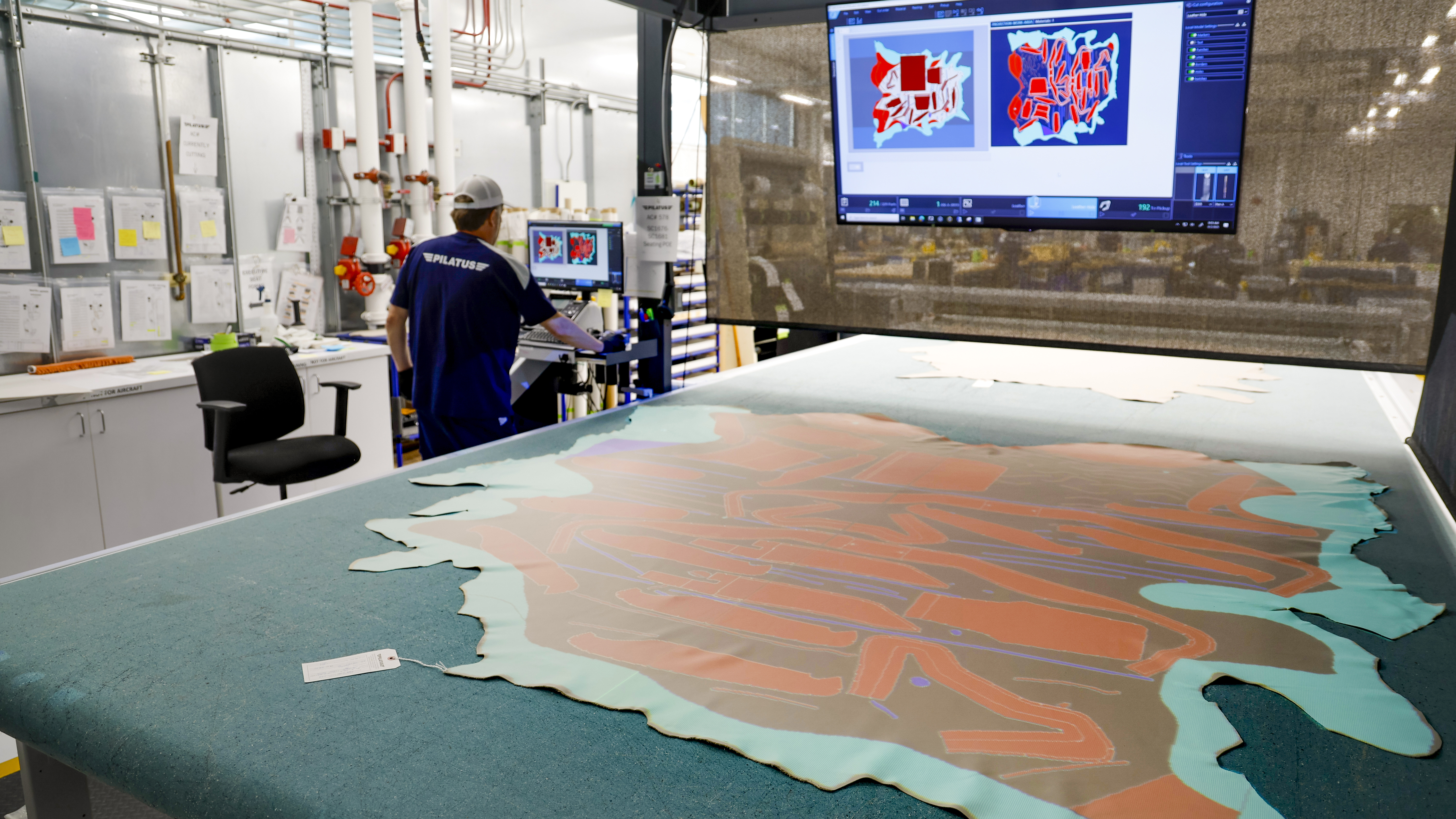

Pilatus opened its U.S. completion center in the mid-1990s and began ferrying airplanes here as soon as they were licensed in Switzerland. Colorado workers paint the new airplanes, install interiors, flight-test them, and deliver them throughout North and South America. The U.S. facility has recently been stockpiling spare parts to support Pilatus aircraft around the world. The warehouse is brimming with components rushed here before tariffs went into effect.

Switzerland charges no tariffs on the products it imports from the United States and has long shared close military, economic, and cultural ties. Swiss International Air Lines, the country’s flagship airline, flies Boeing jets, and its air force uses American-made F/A–18 Hornets and recently committed to buy Lockheed F–35 Lightnings.

Pilatus officials are currently working closely with customers and U.S. dealers to share tariff costs, and they’re consulting with the Swiss embassy, the General Aviation Manufacturers Association (GAMA), and others to reach a long-term solution.

Work for it

The Steamboat Springs ski area comes into view straight ahead as we configure the PC–24 for landing. It’s a clear, sunny morning but high terrain keeps the airport out of our direct view.

“The trick is to follow the highway, make a slight left turn over town, and then look for the airport at your one- to two-o’clock position,” Mead says.

The automation on this single-pilot jet is evident in every phase of flight. FADEC engines make power settings simple and efficient; anti-ice and deice systems turn themselves on and off automatically; if an engine fails in flight, the yaw damper trims out rudder pressure; executing a missed approach is a simple matter of pressing the takeoff/go-around button, advancing the power levers, and raising flaps and landing gear while the autopilot flies the missed approach; spoilers activate automatically upon landing, and the anti-skid brake system is on at all times.

The autothrottles are engaged as we decelerate and descend, and they settle on a lower number each time the pilot extends flaps or landing gear. Mead is flying from the right seat as we follow a Cessna 185 Skywagon to Runway 32.

He clicks off the automation and hand flies the last few miles of a visual approach.

“You’d think the trailing link landing gear on this airplane would make for consistently soft landings, but really, you’ve got to work for them,” he says. “The main landing gear is intentionally stiff for short and rough airfields, so you really want to plant it. This wing is so efficient that it’ll float and float in ground effect if you hold it off.”

An automated voice calls out “100 feet” and that’s Mead’s cue to bring the power levels to idle. The rakish sweep of the windshield and steep downward slant of the nose create an illusion that the airplane is in at a higher pitch attitude than it really is, so Mead counsels new PC–24 pilots to avoid landing flat.

Mead touches down on the main wheels slightly beyond the 600-foot displaced threshold, then stands on the toe brakes as the anti-skid system pulses and the airplane rapidly decelerates. There’s no reverse thrust, ground flaps, or thrust attenuators to shorten the airplane’s landing roll, although spoilers help transfer weight to the wheels for better braking action. As anticipated, the PC–24 stops at mid-field.

We taxi back for three more takeoffs and landings, and each time I’m blown away by the big jet’s nimbleness and the precision with which it can be flown. High or low, fast or slow, the PC–24 does it all with muscular grace.

Swiss consistency

It’s trite to refer the PC–24 as the Swiss Army knife of corporate jets, yet that’s a useful way to think of it. The airplane’s ability to operate on unpaved surfaces is unique in its category, and so is its massive cargo door that can be reached by forklift. Yet it’s just as spacious and luxurious inside as any of its more urbane rivals.

The PC–24 has been flying a full decade yet some of its innovations still impress with their cleverness: The right engine has a “quiet mode” in which it operates as an APU at low rpm without counting as engine operation time; its “thrust vectoring” exhaust system doesn’t really move yet its shape provides a helpful nose-up moment during takeoffs and a nose-down moment during cruise for efficiency.

Other aspects are more artful: Each wing is sculpted from a solid aluminum block and contains five different airfoils. The flying characteristics are sublime throughout the full speed range even without a computerized fly-by-wire system. Double-slotted Fowler flaps allow low approach and landing speeds without the additional weight or complexity of shape-shifting leading-edge devices.

Swiss engineers are known for consistency, and the PC–24 continues the 86-year-old company’s legacy of supreme practicality. Yet, if they had to do it over again, I wonder if the PC–24 designers would insist on off-road capability. Very few PC–24 operators use that hard-won feature, and some insurance companies exclude it. In that sense, a jet that can land on turf or gravel yet chooses not to is like the legions of four-by-four trucks and SUVs that only drive on city streets and highways.

Also, the Honeywell Apex avionics system is amazingly capable, and the fact that it’s installed in both PC–12s and PC–24s makes it easier for pilots to move from one aircraft type to the other. But now that Pilatus has jumped to the Garmin G3000 Prime in its newest PC–12 Pro, and the archrival CJ4 is the launch jet customer for the G3000 Prime, it seems possible—even likely—that Pilatus will make a similar move in its next PC–24 refresh.

Finally, in policy terms, threatening a company like Pilatus—and a country like Switzerland—with punitive tariffs may end up punishing American consumers and workers. Aviation leaders have long encouraged global supply chains, and that degree of specialization has been beneficial in many ways. Pilatus designed the U.S. military’s T–6 Texan II trainer, and it’s been a terrific performer for both the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy when built under license by Beech (now Textron).

Yes, the Swiss have historically used their tradition of international neutrality and opaque banking regulations to maximum advantage (see World War II for details). And if you really want to hold a grudge, the Swiss provided Hessian mercenaries that fought for the British during our Revolutionary War.

But does any of that justify adding millions of dollars to the price of a PC–24 today? Will we get it back in Toblerone chocolate?

Personally, I think we Americans would be better off emulating the Swiss best-practices plainly visible at the Pilatus facility in Colorado, and hopefully, soon, in Florida, too. Apprentices selected from Denver-area schools learn aviation trades while they get college degrees paid for by Pilatus; their hangars are neatly organized and as spotless as surgical suites, and solar power and recycling programs allow Pilatus to supply energy to the local grid.

These are talented friends we’d be wise to keep.