Just say no (go)

Stuck in the NYC clouds

By Christine Naktenis

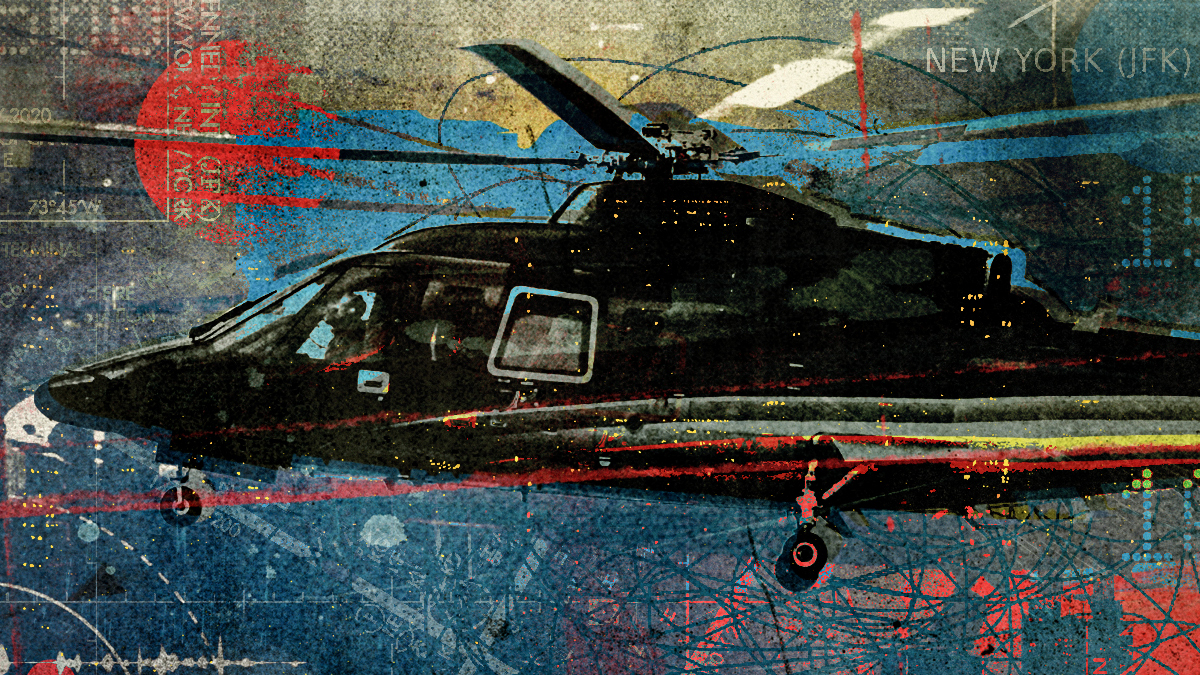

The sky was dark, and the clouds had built to cumulonimbus and towered west of the East River, angrily moving toward our location. The helicopter, a Sikorsky S–76, was already filled with passengers, and the captain was discussing our options with the higher-ups.

Option A: fly the loaded aircraft from the current location to John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK) and get the paying customers to their connecting flights on time, or Option B: look for another job.

The captain stormed out toward the aircraft that I was manning. The rotors were running, and the heat was on for the folks in the back. The weather was one-half mile visibility with 500-foot ceilings and thunderstorms in the vicinity. If we took off, we would not be in compliance with the FAA regulations for our operation, so I told Tim, the captain of the helicopter. He reminded me that he was in charge and that it was his decision to make. I voiced my concerns again, hoping to jar him to his senses. Surely if we both said no, out of concern for our passengers’ safety and that of our crew and helicopter, the higher-ups would be on board with that decision.

I asked Tim again to reconsider, and this time, he unbuckled, went back into the heliport, and called the boss, a guy who sits behind a desk making decisions that affect the rest of us, yet doesn’t have a pilot certificate and does not understand the risk management decision making that a good pilot uses. After a brief exchange on the phone, he walked back in the rain and climbed inside the helicopter.

“We are leaving now and will stay ahead of the weather as we head east toward JFK airport. If the weather deteriorates below a one-half mile visibility, we will turn back.” He spoke quietly and calmly as if trying to reassure himself as well as me.

Tim took controls, and I handled the radios. “I want you to know that I am uncomfortable with this decision,” I said, “and I think that we should be staying on the ground. However, if you decide to take off, I need your word that we will turn back if it gets worse.”

Tim lifted the helicopter into a hover and began the delicate process of backing up over the East River and turning to the north as we departed the East 34th Street Heliport (6N5). We climbed up to 500 feet, and I checked in with river traffic, as was the normal procedure, to let anyone know we would be crossing to the east and heading toward JFK. No one was in the vicinity, which was a testament to the weather conditions. Ahead of us was a five-minute flight to land at the Delta terminal and check our passengers onward to their next connection.

As soon as we got to the east side of the river, the weather deteriorated. We now had one-quarter mile visibility in fog, and it was so dense we had to drop from 500 feet to 350 feet just to see ahead and keep visual contact with the ground. We slowed to about 100 knots and tried to avoid hitting anything in our way as we continued course to JFK. In the meantime, I told Tim that we needed to turn back immediately. “No, it’s not far, and I can make it,” he said. I felt my palms sweat and my heart race as I quickly retorted that I couldn’t make out any definite landmarks in the thick fog and the dark of night.

We continued forward. Things happen fast, even when you are at a crawl of 100 knots—so fast.

I yelled for Tim to take us up and call for an IFR popup clearance. We were in a desperate position. And yet he kept his sights forward into the murky nothingness. And then the desperation surfaced in him.

“Call Kennedy Tower, tell them we can’t see the airport and we are one mile out.”

“Climb,” I yelled. Still, he did nothing.

“Kennedy Tower, this is Helicopter November-One-Two-Three-Four and we no longer have the airport in sight.”

“Helicopter November-One-Two-Three-Four, stay west of the active runways at all times. Landing and departing traffic are using the dual runways Three-One Right and Three-One Left. I repeat, stay west of the runways and the tower.”

We had no visual of the ground, and we were on top of the airport with five passengers on board. This is it, I thought. The feeling in the pit of my stomach was so visceral. I didn’t for a second think we had a chance to land this aircraft upright and not interfere with other airplanes or people on the surface.

As that thought went through my head, the air traffic controller came on again, in a loud and commanding voice: “Helicopter November-One-Two-Three-Four, you are over the airport at 250 feet and one-eighth of a mile from my active runways.”

The Delta ramp control tower wavered in the fog off to our right and at the same height as us. Tim pulled the aircraft into an out-of-ground-effect hover and slowly began to bring it down. Surface lights glowed upward through the mist. I called Kennedy Tower and said we were landing with the Delta tower in sight.

With the aircraft on the ground, we taxied over to parking in silence. The fear in me had turned to anger at the captain for the danger he had imposed on these five passengers in the back of our helicopter. People who had entrusted us with their lives. They had no idea how close they had just come to disaster.

After parking and winding down the blades, we let the people out of the back and wished them well on the next leg of their flight. I grabbed my cellphone and called my boss directly. “I quit,” I yelled into the phone. “How dare you endanger the lives of passengers and people on the ground just to make money.” I hung up and made a second call, one of the utmost importance. I called a car service to pick me up at the airport and take me home. In doing this, I ultimately grounded the helicopter, which couldn’t fly without a co-pilot. I still wonder if Tim would have taken off again if I hadn’t done just that.

I also wonder if being a woman pilot had anything to do with the disregard given to my opinion to cancel the flight and to my call to turn back after crossing the river. I know that if given the chance to make those decisions again while sitting on a helispot at the 34th Street heliport, I would get out of the aircraft before it took off to JFK. I should have been the bigger “man.”

Christine Naktenis is a helicopter ATP and has more than 20 years’ experience flying in commercial operations from Florida to Alaska and the NYC area.