Logbook deception

Why don’t IAs tell it like it is?

The time has come for Bill to put his Beechcraft Bonanza in the shop for its annual ordeal. Manny, one of the A&P mechanics, and Tom, a trainee who is building the hours to qualify for the A&P exam, start opening up Bill’s airplane—removing cowlings, inspection plates, seats, and floorboards. They also start draining the oil and remove the oil filter and top spark plugs.

While Manny and Tom are doing this, Isaac, the IA, is busy going through Bill’s maintenance records and researching all applicable airworthiness directives to ensure that they’ve been complied with and to determine whether any AD-mandated actions are outstanding.

Isaac’s inspection

Manny notifies Isaac that the aircraft is opened up and ready to inspect. Isaac comes over with his clipboard, flashlight, oil filter cutter, and compression tester. He proceeds to inspect the airplane in accordance with his checklist, checking off each item as he goes and writing down any discrepancies he finds. He might ask for Manny and Tom to assist him with jacking the airplane, but he does all the inspection items on the checklist himself, since delegating any portion of the inspection is not permitted.

By the time Isaac has completed his checklist, there are several discrepancies noted: worn brake linings, slack aileron control cables, and a few repetitive ADs that have come due. He goes back to his office and documents these discrepancies on a work order, indicating for each one the corrective action he recommends plus a cost estimate—parts, labor, and outside work. If the shop is ethical, the work order is sent to Bill for review and approval before work begins. (Not all shops do this, but they should.)

Once Bill has approved the recommended work, Isaac assigns Manny, Moe (another A&P), and Tom to perform the work documented on the work order. Manny, Moe, and Tom keep track of their labor hours associated with each work order item, together with any parts they install and any charges for outside work. All of this is entered into the computer. By the time the work is completed, the work order becomes an invoice that is presented to Bill for payment.

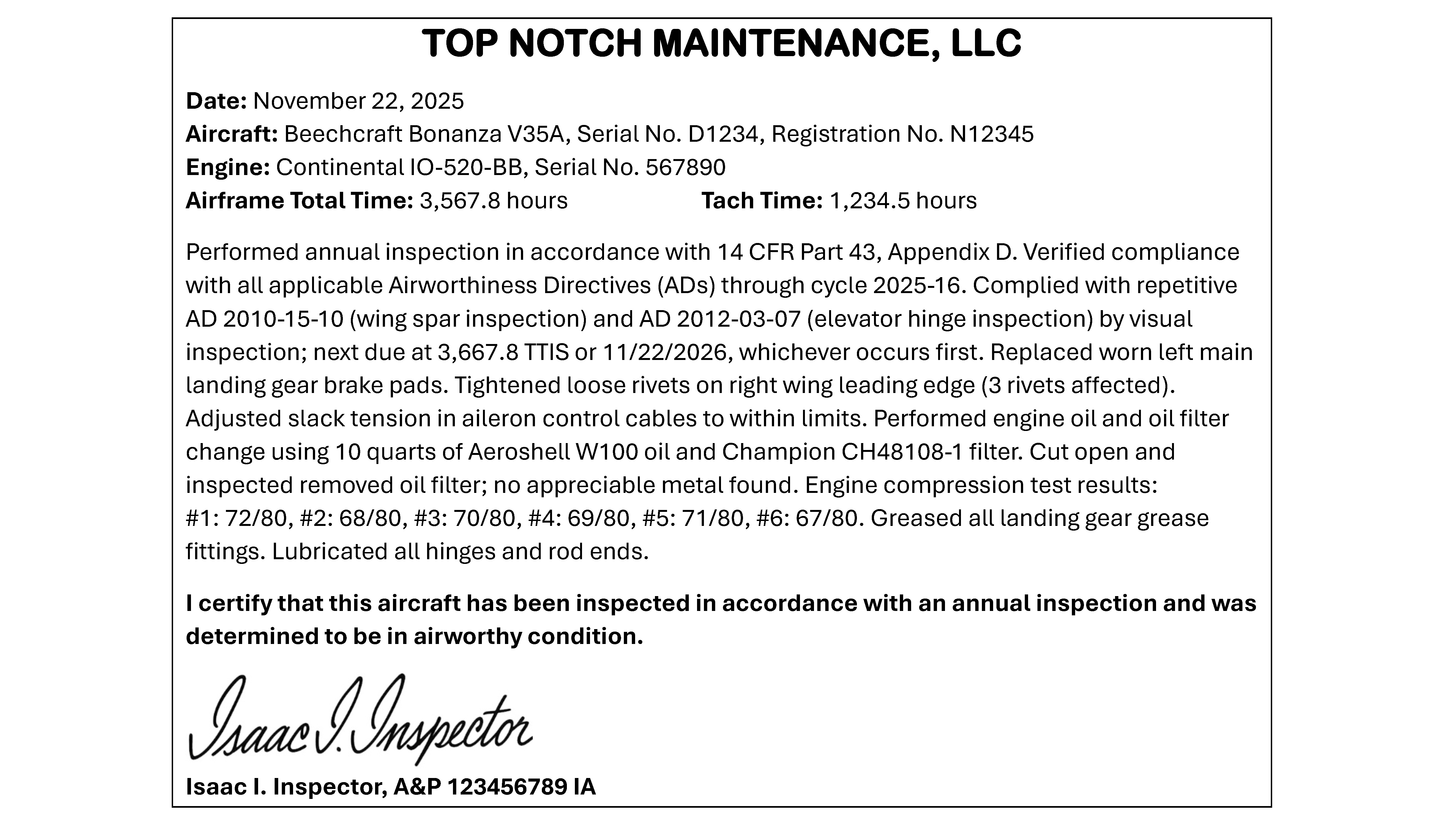

Isaac’s logbook entry

Once Bill’s airplane is buttoned back up, Isaac takes it out for a post-maintenance engine runup, which is required under FAR 43.15 as part of an annual inspection. After verifying that all engine parameters are within acceptable limits, Isaac finally does what Bill has been anxiously waiting for him to do: sign the requisite logbook entry declaring Bill’s Bonanza as airworthy and approving it for return to service.

Over the two decades since I first became an IA, I’ve reviewed thousands of these annual inspection logbook entries and made dozens of them myself. So, I can tell you with high confidence that there is something fundamentally wrong with Isaac’s logbook entry.

Isaac’s deception

It’s a lie! What it describes is not what happened.

To begin with, Isaac certifies that the aircraft was inspected in accordance with an annual inspection (which is true) and was determined to be in airworthy condition (which is blatantly false). When Isaac inspected Bill’s Bonanza, he actually found that it was unairworthy in several respects—recall the worn brake linings, slack aileron cables, and several AD-mandated actions required.

For another thing, the only name and signature on the entry is Isaac’s. What about Manny, Moe, and Tom? They did most of the work, but Isaac’s entry never mentions them.

Perhaps it’s OK because Isaac is the one who approved the work done by Manny, Moe, and Tom? No, he didn’t! Isaac neither supervised Manny, Moe, and Tom, nor inspected their work once they were done. Manny and Moe are both A&P mechanics and don’t require Isaac’s supervision. Tom does require supervision, but Manny was Tom’s supervisor, not Isaac.

See what I mean? The timeline described by Isaac’s logbook entry is all wrong. The inspection came first, not last. It found the airplane unairworthy, not airworthy. The unairworthy items were corrected by Manny, Moe, and Tom, not Isaac.

What the regs require

The content of maintenance record entries is governed by two separate rules in FAR Part 43. One rule (FAR 43.9) applies to records of repairs, alterations, rebuilding, and preventive maintenance—basically everything other than inspections. The other rule (FAR 43.11) applies to records of required inspections, which for most of us means annual inspections. These rules regulate the information content that maintenance records must include, but they’re silent about the form that the records may take. Maintenance records can be organized into physical logbooks, kept on stickies in a cigar box, or maintained electronically in the cloud; the FAA doesn’t care.

Here’s what FAR 43.9 says after deleting a bunch of stuff that applies only to air carriers and Part 135 charter operators:

…each person who maintains, performs preventive maintenance, rebuilds, or alters an aircraft, airframe, aircraft engine, propeller, appliance, or component part shall make an entry in the maintenance record of that equipment containing the following information:

(1) A description…of work performed.

(2) The date of completion of the work performed.

(3) The name of the person performing the work if other than the person [approving the work].

(4) If the work performed…has been performed satisfactorily, the signature, certificate number, and kind of certificate held by the person approving the work. The signature constitutes the approval for return to service only for the work performed.

There are three aspects of FAR 43.9 that are often missed or misunderstood. First, the entry is supposed to be made by the person who actually performed the work, and that person’s name must be included in the entry. Thus, Tom was supposed to make an entry for the work he performed, including his name, even though his supervisor, Manny, was the one who had to approve the work and sign the entry.

Second, the approval signature on a 43.9 entry means only that the work was performed satisfactorily, not that the aircraft is airworthy. So, when Moe tightened the aileron cables, his signature on the 43.9 entry that he was supposed to make meant only that the work he did was satisfactory, not that any of the other unairworthy things that Isaac found had been addressed.

Third, the approval for return to service is only with respect to the work performed. Moe’s approval could not possibly vouch for the work that Manny and Tom performed. Moe’s signature only means that the work he did is airworthy, not that the entire aircraft is airworthy.

Now, what about inspections? Here’s what FAR 43.11 says after removing lots of legalese that doesn’t apply to annual inspections:

The person approving or disapproving an aircraft for return to service…after any inspection performed in accordance with part 91…shall make an entry in the maintenance record of that equipment containing the following information:

(1) The type of inspection and a brief description of the extent of the inspection.

(2) The date of the inspection and aircraft total time in service.

(3) The signature, the certificate number, and kind of certificate held by the person approving or disapproving the aircraft for return to service….

(4) …if the aircraft is found to be airworthy and approved for return to service, the following or a similarly worded statement—“I certify that this aircraft has been inspected in accordance with (insert type) inspection and was determined to be in airworthy condition.”

(5) …if the aircraft is not approved for return to service because of needed maintenance, noncompliance with applicable specifications, airworthiness directives, or other approved data, the following or a similarly worded statement—“I certify that this aircraft has been inspected in accordance with (insert type) inspection and a list of discrepancies and unairworthy items dated (date) has been provided for the aircraft owner or operator.”

A few important points about 43.11: The purpose of an annual inspection is not to make the aircraft airworthy—it is to determine whether or not the aircraft is airworthy. An inspection is a pass-fail exam. There are only two possible outcomes. If the inspector finds it airworthy, he uses the “magic words” of paragraph (4) to approve the aircraft for return to service. On the other hand, if he finds it unairworthy, he uses the alternative set of “magic words” of paragraph (5) to disapprove the aircraft for return to service, and he hands the aircraft owner a list of the airworthiness discrepancies he found. Either way, the inspection is over, and the inspector’s job is finished.

Now, let’s be honest: Have you ever heard of an annual inspection in which the IA found nothing wrong with the aircraft? Neither have I. If it ever happened, the IA would need to have his vision and blood alcohol level tested.

But even though virtually all annual inspections find at least some discrepancies, the correction of those discrepancies has no place in the 43.11 entry. Correction of discrepancies belongs in a 43.9 entry made by the person who did the work, not in a 43.11 entry made by the IA who did the inspection.

Isaac’s entry revisited

So, what kind of animal is that logbook entry that Isaac gave to Bill? It isn’t a proper 43.11 entry or a proper 43.9 entry. It’s some sort of hybrid entry containing both 43.9 and 43.11 elements blended together like a smoothie. The 43.9 elements lack accountability—they don’t say who did the work or who approved the work. The 43.11 elements misrepresent the outcome of the inspection, indicating that the inspector found no airworthiness discrepancies, which is clearly not true.

In short, Isaac’s entry is a hot mess.

So, how should Bill’s annual have been memorialized? It seems to me that the regulations are pretty clear about that. First, Isaac should have made a 43.11 entry certifying that Bill’s aircraft had been inspected in accordance with an annual inspection and that a list of discrepancies and unairworthy items had been given to Bill. After all, that’s exactly what happened, right?

Then, there should have been at least three 43.9 entries, one each made by Manny, Moe, and Tom. Tom’s entry would be signed by Manny, his supervisor. Manny’s and Moe’s entries would be signed by themselves.

Isaac’s 43.11 entry disapproved the aircraft for return to service, as it should have, since the airplane was found to be unairworthy. The 43.9 entries signed by Manny and Moe cleared each of the discrepancies on the 43.11 discrepancy list that Isaac gave Bill. Collectively, all these entries taken together should be sufficient to approve the aircraft for return to service.

But just to tie the ribbons on things, it would be nice (although arguably unnecessary) if someone made one more logbook entry saying that a review of Isaac’s discrepancy list and Manny’s, Moe’s, and Tom’s entries reveals that all the discrepancies had been resolved. Such an entry would not be a 43.9 or 43.11 entry—it would be more like a memo. Who should sign it? Because Isaac conducted the post-inspection engine run under FAR 43.15(c)(2), it would be reasonable for him to make this entry, although any A&P could also do so. Arguably, even the owner could do so. After all, it’s the owner who is ultimately responsible for getting all the airworthiness discrepancies corrected.

As a student of FAA regulations, I think this is the right way to memorialize Bill’s annual ordeal in a fashion that is fully compliant with the regs. Yet nobody does it this way. Virtually everyone does it the way that Isaac does. Obviously, the FAA knows this and doesn’t seem to mind.

Am I the only one who is bothered by this? Maybe I forgot to take my meds.

savvyaviation.com

savvyaviation.com