Ice advice

Tailplane stalls behave differently

That would be the issue of tailplane icing. The “tailplane” term applies to either the horizontal stabilizer or stabilator, according to the airplane design. And icing-induced tailplane stalls, while seemingly rare, behave differently than conventional wing stalls.

It’s no surprise that many are not familiar with tailplane aerodynamic disruptions. Those who fly in icing conditions usually focus their attention on inspecting the wing’s leading edges for any sign of ice buildup. Be sure to monitor the airspeed indicator, outside air temperature, and other gauges, and of course, the pitot heat to make sure it is working properly. Bear in mind that ice first accretes on small-radius leading-edge objects. Things like windshield probes, posts, struts, steps, antennas, and even rivet heads will give the first indications that you’re collecting ice. Scanning a tailplane for ice can be neglected or even impossible if the view is blocked.

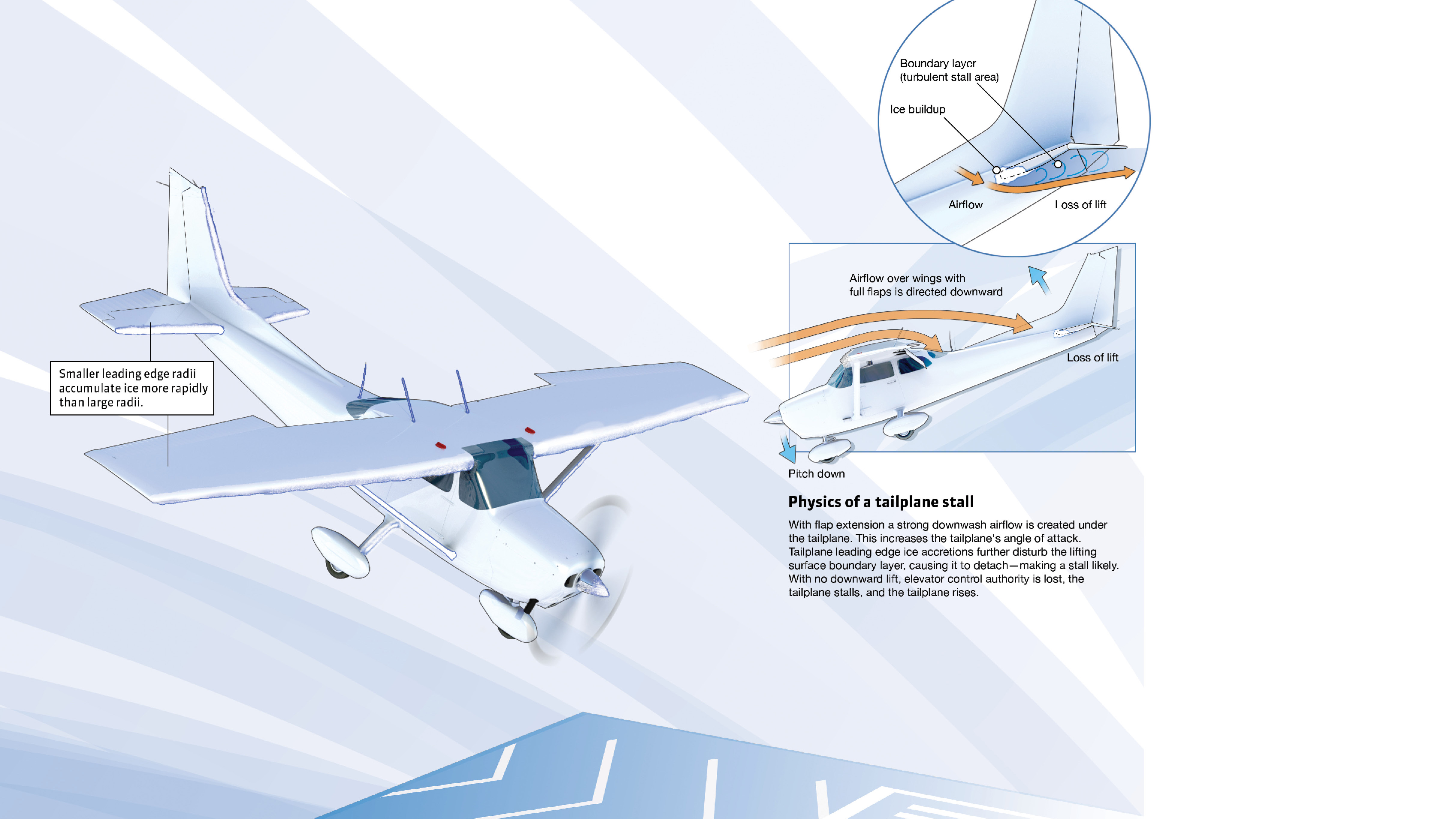

Wing and tailplane leading edges typically have differences in their radii. Wing leading edges are larger and rounder than tailplane leading edges. This means that tailplane ice-collection efficiencies can be far greater than those of the wings.

This is important to remember, should ice begin to accrete on your wing leading edges. The tailplane leading edges are also icing up—and at a faster rate than the wing buildups. Let these buildups continue, and the wing and tailplane surfaces’ stall speeds rise and in certain situations can cause drastically adverse handling characteristics. We all know that wings produce lift in an upward direction and that when wings stall, they lose that lift and drop. Tailplanes also produce lift, but in a downward direction; when they stall, they rise.

Ordinarily, a balancing act between wing and tailplane lift creates longitudinal stability as the airplane pivots about its center of gravity. But throw in icing conditions, and all bets are off. Because tailplanes collect more ice, they can stall before the wing does. When that happens, the tail rises abruptly while the nose pitches straight down. You’re now poised to spear the Earth at a 90-degree angle. Especially if you’re at a low altitude.

The worst-case scenario happens in large-droplet, clear- and freezing rain icing conditions, on an instrument approach, at a higher-than-normal airspeed, and with flaps extended. The faster you fly, the faster ice can build. Flap extension deflects the wing’s trailing airflow downward, increasing the tailplane’s angle of attack. Any tailplane ice accretions can aggravate the condition, causing premature flow separation on the lower surface of the tailplane. An ensuing stall causes an abrupt pitch-over. Headwind gusts and downdrafts are other culprits. These increase the tailplane’s angle of attack, helping to bring it to a stall.

Tailplane stalls have been the subject of ongoing study by NASA’s Glenn (formerly Lewis) Research Center in Cleveland, which specializes in icing issues. Fatal accidents in 1958 and January 1963 involving the Vickers Viscount, a four-engine, 40-seat turboprop, were studied, along with 18 other fatal crashes involving newer turboprops such as the Saab 340, ATR 42, and Embraer Bandeirante.

Witnesses to the first Viscount crash watched the airplane as it made a night visual approach in freezing rain—the worst of the worst large-droplet icing condition—as it turned base, then final. After rolling out, the airplane pitched up slightly, then nosed 90 degrees down and crashed short of the runway. The crew of a third Viscount icing incident in February 1963 said it experienced a series of two or three pitch oscillations above and below the ILS glideslope; they said they never felt like they had total pitch control. A post-flight investigation showed ice on the horizontal stabilizer leading edge. It was determined that this, together with specific airspeeds and flap settings, caused the tail to stall.

A second NASA workshop also examined general aviation airplane incidents on approach in large-droplet icing conditions. A Piper Cherokee pilot experienced a stabilator stall after extending the flaps. The stall was so violent that the airplane pulled negative Gs, but when the pilot retracted the flaps, the airplane recovered. A Piper Malibu pilot had an uncommanded pitchover with flap extension; when he retracted the flaps, he regained control. There was very little ice on the wings at the time, but a half-inch large-droplet, double-horn ice accretion was present on the horizontal stabilizer. In another tailplane stall event, there was one inch of ice on the wings, two inches on the windshield wipers, and three inches on the tailplane leading edges.

The NASA workshops, held in 1991 and 1993, were among the first efforts to produce formal advice on flight in tailplane icing conditions. This guidance included warning signs and recovery procedures dealing with tailplane stalls, which you normally wouldn’t see published in flight instruction textbooks or pilot operating handbooks. Pilots—especially instrument pilots—should learn them and be prepared to hand-fly any approaches in icing conditions, as using an autopilot can mask the pitch sensations and tailplane behavior that precede a stall.

Partner-provided content Avoiding ice and freezing levels /

How to Use SiriusXM & Garmin

As pilot in command, you need to know if and where icing conditions are along your route of flight. Learn how to use Freezing Levels, Icing NOWcast, airmets/sigmets, and pireps to help you avoid icing conditions on your next flight by watching SiriusXM.com/avoidice.