Flying skeletons and electric hummingbirds

A tale of floaters and foamies

Extreme flying doesn’t always mean speed. It can refer to a lack of speed, too. Here are two model airplanes that are polar opposites, as are their pilots. One lingers on the edge of an aerodynamic stall for more than a half hour and will star in its own documentary called Float, while the other zooms about with electric power, hovering on its tail—or nose—teaching even the birds new tricks. Both have a greater connection to general aviation than you’d think.

Flying skeletons

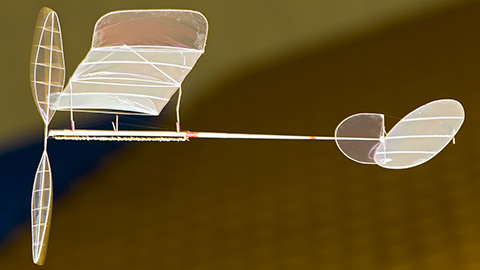

The rubber-band-powered airplanes known to most of us exhaust their energy in seconds, usually slamming into a wall or the furniture and drawing a protest from the nearest parent. But those classified by the Academy of Model Aeronautics as “F1D” appear to fly in slow motion, turning their propellers once each second no matter how tightly wound the rubber band, thanks to an ingenious constant-speed propeller. These are free flyers with rudders set to fly in circles—nudged back on course with a line hanging from a helium balloon. F1D models are the elite of any endurance contest, with a one-hour flight established as the ultimate goal.

Models similar to the F1D, but with longer wings, have achieved the elusive hour goal while flying inside the cavernous New Jersey hangar that the dirigible Hindenburg would have used, had it not exploded. John Kagan of Strongsville, Ohio, flew such a model—in what's known as the "unlimited" category—for more than an hour and is the 2000 F1D world champion. Kagan and hobbyist Steve Brown, whose aircraft fell a few minutes short of an hour, are the only two in the history of modeling to reach or nearly reach the one-hour mark. F1D wings are limited in size so they will fit in a transparent carry-on case for airline travel.

They fly—always indoors—at one mile per hour. Walk too fast carrying one, and its structures will fail in the resulting breeze. Launching is more of a release than a toss, because tossing it would tear it apart. The wings are mounted to the fuselage by toothpick-size balsa supports. The wing is stiffened by a thread of boron running along the wing and down the supports.

They fly—always indoors—at one mile per hour. Walk too fast carrying one, and its structures will fail in the resulting breeze. Launching is more of a release than a toss, because tossing it would tear it apart. The wings are mounted to the fuselage by toothpick-size balsa supports. The wing is stiffened by a thread of boron running along the wing and down the supports.

Good rubber for the "motor" is the same to an F1D pilot as drugs are to an addict. They know the "crown jewel of rubber" was made in May 1999, refer to it as "5-99," negotiate for supplies, and won't tell you their source. It is associated with many record flights. The balsa framework of the wings has the thickness of a shoestring. The body is just a balsa stick. Transparent film only microns thick—used in military capacitors and reflecting rainbow colors from its surface when viewed at an angle—covers the wings and tail. Heat from your body can cause an aerodynamic stall if you stand under it before it has reached 10 feet.

John Kagan was the world champion in F1D competition in 2000 and won silver in 2010. He is also the holder of record for a one-hour flight, using the Unlimited category craft.

The longest an F1D airplane has flown is 39 minutes and change, according to Benjamin Saks, an F1D builder who is trained in architectural design but has devoted himself fulltime to producing the documentary Float . He is raising funds for the movie and hopes to have it completed in 2013. Saks, located in Pittsburgh, and music video filmmaker Phil Kibbe of Cleveland, plan to follow contestants around the world as they prepare for the 2012 competition. "I saw the plane on an iPhone and thought it was slow motion. I was blown away when I found out it wasn't," Kibbe said. "The guys involved in the hobby all have unique, endearing character traits, interesting in and of itself."

Their numbers include scientists, inventors, architects, and engineers. One, Saks said, worked on the NASA Helios project—the solar panel that NASA formed into a flying wing.

While in high school, Saks competed on the United States Junior F1D team, traveling to Romania where competition took place in a windless salt mine 600 feet underground. The prize? Little more than a trophy and personal achievement.

Rubber-band airplanes had their heyday in the 1930s and 1940s, but today interest is dropping rapidly.Supporters of the hobby hope the movie and this article will inspire a new generation to accept the challenge of building airplanes that weigh the same as three one-dollar bills.

Winner of this year's national competition was former airline captain Larry Calliau. He's among the few people in the world with the patience and miniature engineering skills needed to build the F1D that weighs, with the rubber installed, the same as three one-dollar bills.

There may be as many as 1,000 people building the aircraft worldwide, but when the head count is taken at world events, no more than 70 compete, said former world champion and 2011 national F1D champion Larry Cailliau of Payson, Arizona. He is a retired airline pilot who flew airliners weighing 70 to 100 tons—as opposed to the three-gram F1D.

Why doesn't Cailliau just go to the local airport and rent an aircraft if he wants to stay close to aviation? "I've flown rubber-band airplanes since I was a little boy, 12 years old," Cailliau said.

There are 30 hours of work in building an F1D, where tolerances are measured to a thousandth of an inch. It is very satisfying to not only build a good one, but to win the world competition—a title he captured when his aircraft, flying characteristically nose high as though it might stall, flew for 35 minutes and 15 seconds.

"You're seeing a movie in slow motion," Cailliau said. "It floats around like a bubble."

Most contestants use a homemade torque meter to calculate when the rubber band is about to break, usually at 1,600 turns, then they back off a few turns. Eight-time world champion Jim Richmond of Carmel, Indiana, somehow uses 1,700 turns. That's one of his secrets, but not the biggest. Unlike most, he has used a constant-speed propeller that uses balsa-wood levers to grow in length, rather than change the pitch of the blades. Another secret is experience. Now 83, he has made rubber-band airplanes since he was 5, when his grandmother had to read the 10-cent plans to him.

Charles Slater of Fort Lauderdale, Florida, was a designer of medical equipment until he sold his successful company, and he is an F1D builder. "It is on the very edge of a human's ability to handle and manipulate the components of a flying machine," Slater said. He said he feels the concentration on miniaturization aided him in building medical exploratory equipment.

"It's not just a hobby. It's not just a sport. It's a lifestyle," Saks said.

Foamies at a hover

Styrofoam airplanes are the exact opposite of F1D models, but the links to general aviation remain. These electric radio-controlled airplanes are still made by hand for competition, but there the similarities end. They draw a crowd, win cash prizes, and attract youthful participants to a hobby that grows every year. The pilots at the top even have sponsors.

Rob Eberle competes in the self-launched category that tosses models up to 100 feet.

Videos from a company called Higher Plane Productions, and from fans, flood the Internet with shots of model airplanes hanging on a prop—no torque roll—or even hovering nose down inches above the floor. A video in the digital version of this article shows the 2011 second-place winner R.J. Gritter during a 2010 performance, and was produced by higherplaneproductions.com. You'll find 2011 videos there and on YouTube.

The competitions are the invention of Tom Kroggel, former manager of the National Flight Services FBO at Toledo, Ohio. Kroggel left the FBO business and created a company called TnT Landing Gear, located in Toledo, after discovering he had a profitable knack for building model airplane landing gear.

He invented the world contest you may have seen in videos called the Electric Tournament of Champions (ETOC), conducted in a high school gym in Toledo each year. Typically, 5,000 people pay $10 each for the two-day event, allowing cash prizes of a few thousand dollars to be awarded. That's enough for the international competitors like Gernot Bruckmann of Austria, the 2011 winner, to pay for his trip to the United States. At 19, he is a manufacturer of model airplanes.

Email the author at [email protected].