Postcards: Trek to northern Canada

Arctic Lodges: The lure of Arctic fishing

Photography by Chris Rose

The gravel runway is the first sign of human habitation we’ve seen in the past 100 miles, and it’s a welcome sight. Far from any roads, harbors, or settlements, the Malcolm Island Airstrip (CJS2) covers the entire length of a low, tree-lined outcropping at Reindeer Lake, a massive, 200-mile stretch of pristine water in northern Canada that offers some of the world’s best lake trout and northern pike fishing.

A steady rain streaks across our Bonanza’s windshield as we fly overhead the red-roofed cabins at our destination, Arctic Lodges, located on a separate island, to rattle the windows and let our hosts know we’ve arrived. Arctic Lodges owner Ray Littlechilds informs us via radio that he’ll pick us up by boat at the airstrip in 30 minutes. We lower the gear and prepare to land at Malcolm Island just four miles distant.

A steady rain streaks across our Bonanza’s windshield as we fly overhead the red-roofed cabins at our destination, Arctic Lodges, located on a separate island, to rattle the windows and let our hosts know we’ve arrived. Arctic Lodges owner Ray Littlechilds informs us via radio that he’ll pick us up by boat at the airstrip in 30 minutes. We lower the gear and prepare to land at Malcolm Island just four miles distant.

There’s no wind sock on the little-used strip, but it’s easy to tell from the ripples on the water that a steady breeze out of the southwest favors Runway 18. We touch down just beyond a slight hump at the extreme north end of the strip and roll to midfield, where a wrecked and forlorn DC–3, the victim of a 1969 mishap, instills caution from its out-of-the-way place by the trees. Our arrival startles a flock of Canada geese into honking, flapping, protesting flight as we roll by.

AOPA photographer Chris Rose and I have covered about 1,500 miles from Frederick, Maryland, in N290S, a 1972 Beechcraft Bonanza A36, to reach this remote and rugged wilderness on the edge of the Canadian arctic. We taxi to a sheltered corner of the island and shut down the Continental IO-550 that’s labored so steadily and so long to bring us here. We’ve crossed three Great Lakes and innumerable smaller ones along the way, and we put on jackets for the first time in months as we quietly soak in our exotic northern surroundings. The stifling heat, humidity, and familiar bustle of an East Coast summer seem much more than a dozen flying hours behind us.

Rose unpacks our belongings and sets them under the airplane’s right wing to keep them dry. I secure the Bonanza using rocks the size of grapefruits as wheel chocks, and triple- and quadruple-check to make sure the electrical master switch is off and the ignition key is in a zippered pocket.

Other than the patter of steady rain, the silence is overwhelming.

Arctic Lodges is owned by Ray and Jan Littlechilds (center, top). The main lodge (center, bottom) is the place for driftwood fires, sumptuous meals, and no shortage of fishing and flying stories. The gravel airstrip (far right) is a huge asset to Arctic Lodges.

A huge asset

Arctic Lodges at Reindeer Lake is the realization of one man’s vision for this corner of the far north, the late Fred Lockhart. A geologist for the Hudson Bay Mining and Smelting Co., as well as an outdoorsman and seaplane pilot, Lockhart was enchanted with Reindeer Lake and its possibilities as a paradise for hunters and fishermen. He bought a long-term lease on the land in 1950 from a local trapper and began promoting it to fellow outdoorsmen, but transportation was a nearly insurmountable obstacle. The nearest sizeable town, Prince Albert, is six hours away by car—and then it takes at least two hours more to get to the lodge by boat.

Floatplanes can get a few visitors at a time to the camp’s rustic cabins, but they are relatively slow and expensive to operate, and there’s no place here for them to refuel.

Lockhart’s answer was to convert one of the lake’s nearly 5,000 islands to a gravel-surface landing strip where airplanes with wheels (or skis) could take off and land. And one winter in the early 1950s, he bought a front-end loader and hired a crew to drive it 400 miles across mining roads and frozen lakes to the island. (The heavy machinery is still on the island, and it’s used each spring to clear and grade the 4,700-foot strip.)

Lockhart attracted fishermen and hunters from all over Canada and the United States using chartered aircraft that included lumbering PBY Catalina flying boats and Douglas DC–3s. (The ill-fated Gooney Bird that remains is said to have been done in when the crew forgot to remove the rudder lock before takeoff.)

Lockhart attracted fishermen and hunters from all over Canada and the United States using chartered aircraft that included lumbering PBY Catalina flying boats and Douglas DC–3s. (The ill-fated Gooney Bird that remains is said to have been done in when the crew forgot to remove the rudder lock before takeoff.)

The lodge thrived for many years with Lockhart and his wife Linda running it. But he eventually became ill, retired, and passed away, and the family decided to sell. Littlechilds, a former Canadian wildlife conservation officer who knew the Lockharts when they operated the lodge, fell in love with this part of the far north when he was posted here 20 years ago. He bought the lodge and, with wife Jan and son Kelly, has made great efforts to upgrade the facility.

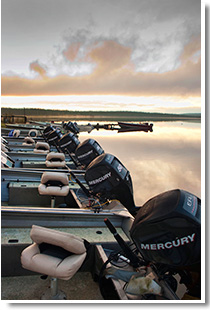

Everything from the oven, pool table, generator, and fuel had to be brought in by boat or barge. The Littlechilds have a fleet of a dozen 50-horsepower skiffs, and they are typically operated by Native American guides who bring two guests each on fishing excursions. There are six similar lodges on the 200-mile-long lake, but Arctic Lodges is the only one with an airstrip, and the Littlechilds use it to attract general aviation pilots from Canada and the United States.

“The runway is a huge asset to Arctic Lodges, and it has been ever since it was built,” Ray says. “It makes us unique and accessible despite our remote location.”

Rest your arms

Rest your arms

A 20-minute boat ride brings us to Arctic Lodges where, despite a steady rain, Jan welcomes us at the dock. We deposit our gear in one of the log cabins, then dry out by a roaring driftwood fire in the main building. The taxidermy inside the lodge suggests some of the possibilities: a toothy northern pike that measures four feet in length, and a rotund lake trout that weighed 70 pounds when it was caught (and released) by a guest a year ago.

The sunlight never disappears during the summer solstice here. But this is the last week in August, and sunset takes place around 8:30 p.m. with twilight lasting another hour.

The rain stops. I pull out a fishing rod and make a few casts from the dock in front of the lodge, just testing the equipment, and am surprised to reel in a 20-inch trout and a 22-inch pike. Littlechilds tells us those are just warm-up fish. “Rest your arms,” he said. “They’re going to get tired tomorrow from reeling in fish.”

Extraordinary experiences

Our guide is George Clarke, 62, a commercial fisherman and member of the Woodland Cree tribe who has lived near Reindeer Lake his entire life. He navigates the seemingly endless lake’s countless twists and curves by memory. Clarke doesn’t carry a GPS and disdains the electronic fish finder.

Our guide is George Clarke, 62, a commercial fisherman and member of the Woodland Cree tribe who has lived near Reindeer Lake his entire life. He navigates the seemingly endless lake’s countless twists and curves by memory. Clarke doesn’t carry a GPS and disdains the electronic fish finder.

I ask him whether he ever gets lost because so many parts of the lake look the same, and he finds the question hilarious. His normally stoic, weathered face breaks into a beaming smile and he’s wracked with laughter. Throughout the day, whenever something reminds him of my question, he smiles and laughs some more.

He tells a story about his grandfather, an Irish emigrant to Canada after World War I who became a policeman, then a fur trapper in this area. He married a Native American woman and had 11 kids, eight of them sons, and Clarke has been one of the most common names in the region ever since.

He kills the engine and our boat drifts to a stop.

“Lots of trout here,” Clarke says, and Rose and I cast our lures. Less than one minute later, a five-pound lake trout is attached to my metal jig.

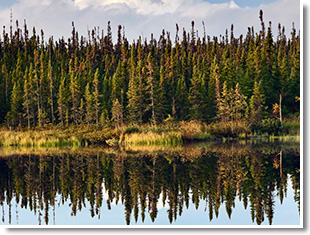

Later, we move from the deep water to a shallow, reedy area in search of northern pike. The shoreline is covered with scrawny pines and red spruce trees. A fish habitat designer couldn’t invent a more ideal location. Whether trolling or casting, it’s rare to go more than 10 minutes without a fish on one of our lines. We use barbless hooks and release every fish.

Later, we move from the deep water to a shallow, reedy area in search of northern pike. The shoreline is covered with scrawny pines and red spruce trees. A fish habitat designer couldn’t invent a more ideal location. Whether trolling or casting, it’s rare to go more than 10 minutes without a fish on one of our lines. We use barbless hooks and release every fish.

At midday, most fishermen keep at least one fish and grill it on the beach for a sumptuous “shore lunch.” But we’re expecting a group of pilots from Colorado Springs, Colorado, to arrive, so we carry a transceiver and stay near the airstrip. We explore the island and the wrecked and stripped, but remarkably well-preserved, DC–3, listening as the first of five airplanes arrives overhead and lands on Runway 36.

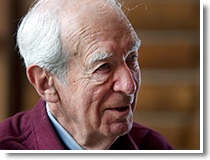

The group is led, as it is every year, by Don Bates, 82, a Canada native and U.S. citizen who attended Colorado College on a hockey scholarship in the early 1960s and stayed throughout a long and successful career in the insurance industry. A 50-year AOPA member, Bates began flying to this region to visit his parents in Prince Albert and fish at Reindeer Lake. His first flying trip here was in a Cessna 150, and now he owns and flies a Cessna 210. The other aircraft on this excursion include another 210, a 337, a 206, and a Bonanza A36. They carry a total of 20 visitors.

None of the airplanes has been modified for bush flying, and the most unusual thing about them is how ordinary they look. There aren’t any tundra tires or vortex generators or STOL kits among them. “People think that you need a specialty aircraft to come to places like this, but you really don’t,” Bates said. “It’s nice to have the speed and the range of a high-performance airplane. But I’ve made this trip in a 150, a 170, a 172, a 182, and a 210. As long as you plan ahead and prepare, it can be done reasonably and safely.”

None of the airplanes has been modified for bush flying, and the most unusual thing about them is how ordinary they look. There aren’t any tundra tires or vortex generators or STOL kits among them. “People think that you need a specialty aircraft to come to places like this, but you really don’t,” Bates said. “It’s nice to have the speed and the range of a high-performance airplane. But I’ve made this trip in a 150, a 170, a 172, a 182, and a 210. As long as you plan ahead and prepare, it can be done reasonably and safely.”

The pilots range in age from their 20s to their 80s, and some belong to families for whom this trip has become an annual rite. Bates’ son David, a lawyer and GA pilot living in Houston, has been flying here since he was a child. “Flying is something that was a part of life for our family when I was growing up,” he said. “Coming places like this was just normal. It’s only much later that I began to appreciate the tremendous effort my parents made to provide us with such extraordinary experiences at such young ages.”

With the eagles

The weather turned atrocious the next day with heavy rain, thunder, and powerful east winds pushing whitecaps on normally placid portions of the lake. This is the first year that Arctic Lodges has had an Internet connection, and I watched the weather forecasts with interest.

It would have been nice to wait out the weather and keep fishing until the sun came out. But a large group was scheduled to fill the cabins in a few more days, and Rose and I had other work and family obligations at home. Rain and low clouds were expected to continue for several days at Reindeer Lake, but the forecast was much more promising 100 miles south. A break in the weather at noon the next day gave us an opening, and we decided to take it. We’d been at the lake less than 72 hours.

I filed a VFR flight plan by phone to Flin Flon, and Ray Littlechilds humored us by letting us catch a few more fish from his boat before racing to the airstrip on a jarring, high-speed ride through intermittent rainsqualls. Soon we were loading our soaked gear into the airplane.

I’d practiced simulated soft-field takeoffs in the Bonanza on the northbound flight, but now it was time to do one for real. I taxied slowly and at low power to decrease the chances of picking up a stray rock and damaging the prop, and then performed the run-up checklist at reduced power for the same reason.

With the long runway there was no need to bring the engine to full power immediately, so I very gradually pushed the throttle forward during the takeoff roll and held the yoke aft. The stall warning horn chirped as the main wheels lifted off the gravel surface, and the airplane accelerated through the cool, choppy air.

We overflew the lodge to let Littlechilds know we were airborne and on our way south along with the geese and the eagles we’d watched during the previous days. True to the forecast, the skies parted about 45 minutes later and it was sunny and clear at our fuel stop.

We overflew the lodge to let Littlechilds know we were airborne and on our way south along with the geese and the eagles we’d watched during the previous days. True to the forecast, the skies parted about 45 minutes later and it was sunny and clear at our fuel stop.

The remoteness and isolation of the Canadian landscape had spooked me on the way up, and I’d actually turned down a direct routing in order to remain on the airways. But we’d take a straight-line course south over Lake Manitoba and the wheat fields of Saskatchewan that would allow us to reach the United States nonstop.

On the way up we had filed an IFR flight plan and eAPIS computer customs notification of our impending return from Flin Flon, and four hours later, we touched down in Duluth, Minnesota. The U.S. Customs agent scanned our airplane with a Geiger counter and seemed incredulous that we didn’t bring any fish home with us, but Rose and I thought it better to leave them in Reindeer Lake where they’d have plenty of company.

Hopefully, we’ll return someday and see them again.

E-mail the author at [email protected].

Flying in Canada

The flight to Arctic Lodges was my first time flying in Canada, or crossing an international border as pilot in command, and it led to a frantic paper chase the week before departure. To fully comply with regulations, I needed an international radio/telephone license from the FCC as well as an “English proficient” stamp on my pilot certificate. I applied for each via the Internet on a Monday, and to my surprise and delight, they arrived in my mailbox on Friday of the same week. (The FCC dinged me for $60, and the new FAA certificate cost $2.)

The flight to Arctic Lodges was my first time flying in Canada, or crossing an international border as pilot in command, and it led to a frantic paper chase the week before departure. To fully comply with regulations, I needed an international radio/telephone license from the FCC as well as an “English proficient” stamp on my pilot certificate. I applied for each via the Internet on a Monday, and to my surprise and delight, they arrived in my mailbox on Friday of the same week. (The FCC dinged me for $60, and the new FAA certificate cost $2.)

Online preparation for the U.S. Customs computerized eAPIS filing came through the AOPA Air Safety Institute. I filled out the manifest in advance and activated it just prior to departure from Basler Flight Service in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. I followed up with a phone call to Canadian customs to let them know we’d be arriving at Winnipeg International Airport about four hours later. The IFR flight plan to Winnipeg, and the flight itself, seemed no different than a domestic instrument flight. After landing, we taxied to the Kelly Western Services FBO and called Canadian customs via cell phone. The customs official said there would be no physical inspection of our airplane (or the documents I’d hurriedly gathered) and to enjoy our stay in Canada. That was it.

The next day’s 3.5-hour flight north to Flin Flon was also on an IFR flight plan, but the procedures were a bit unusual. In the increasingly remote areas, radar coverage became spotty and then nonexistent, and the transponder reply light stopped blinking completely a couple hours north of Winnipeg. The ATC frequency became eerily quiet, too.

About 20 miles away from Flin Flon, I was told to contact Saskatoon Radio, a flight service station that controls traffic throughout the area sans radar. Complying with “Sassy radio’s” instructions, I notified the controller when entering the airport’s control zone (a 10-mile radius), let her know when I was on final approach, and that I had landed and cleared the runway. (Fuel prices were about 50 cents a gallon more than home.)

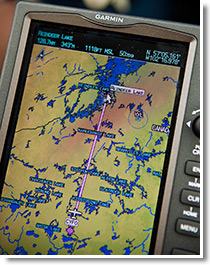

The final leg of the trip to Malcolm Island was an hour-long VFR flight over a dramatic vista of seemingly endless blue lakes and rocky, undulating ground. The magnetic compass wandered more than 30 degrees off heading as we continued north through areas where magnetic disturbances of 180 degrees are common, but the magenta line on the Bonanza’s Garmin GNS530 pointed unerringly to the lat/long I’d manually entered for our destination.

Our airplane was equipped with a standard ELT that broadcasts on 121.5 MHz (Canada doesn’t yet require 406 MHz ELTs), and Rose and I both carried personal Spot GPS messengers.

All flights in Canada require flight plans, and this one was filed by phone and then activated with Saskatoon Radio. Once we took off and departed the control zone, however, there were no more radio calls. On the ground at Malcolm Island, I cancelled our VFR flight plan and confirmed our safe arrival using the lodge’s satellite telephone. —DH