Bob Gannon’s excellent adventure

The world was not enough, so he circled it twice

Most general aviation pilots would love to fly an average of 220 hours a year. Flying that much for a decade would be a dream come true.

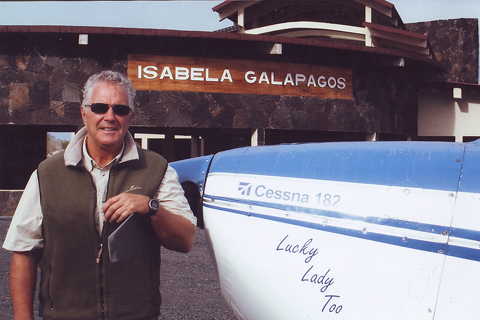

Bob Gannon did all that, but he upped the ante, flying 2,200 hours in 10 years, and making 1,200 landings in 155 different countries, on every continent.

He became an “earthrounder.” Twice.

And his trek required roughly 300 hours airborne over oceans, hand-flying an elderly single-engine Cessna 182 whose most sophisticated avionics was an ancient GPS for which you can’t even get batteries anymore. He says he’d do it that way again.

The first question about Gannon’s adventure had to be, “Why?”

“I’m a curious guy. I like experiences. You walk away with an interesting story, or a little knowledge, or a little wisdom,” Gannon said.

Or all of the above.

On Jan. 8, Gannon, 60, returned home to San Diego’s Gillespie Field, having completed two circumnavigations of the globe, in opposite directions. A flight from central Mexico to a crowd of waiting well-wishers and news media in San Diego served as the last leg of the journey that began in October 2000.

In an interview with AOPA in which he offered some insights on long-distance flying, Gannon admitted to feeling slightly out of sorts for not having another flight leg to plan.

That’s not to say that he expects to remain ground bound. He’s planning a month’s flying with a friend in June, and there are other projects under consideration.

“I’ll get another taste of the adventure,” he says.

It’s hard to imagine topping the adventure Gannon has already had. This was no great race, no frantic rush to create a speed record or beat some artificial deadline.

“My attitude was, I wanted to see the world and this was my only chance of getting around it,” he said. But not in haste; he wanted to see the places where he landed and take in the highlights.

“Whether it’s geography or animals or people or customs, I feel like I get to know it before I go on to the next country,” he said. “I don’t fly in a straight line.”

Click the image above to view a slideshow.

Click the image above to view a slideshow.

That’s how Middle Eastern hot spots become logbook entries. It’s how you find yourself in a standoff with a Venezuelan military man who’d like to make your airplane part of his inventory. That happened on Isla de Margarita while heading for Aruba after landing at almost every island in the Caribbean, except Cuba, Haiti, and Montserrat, and after attending a carnival in Trinidad. It’s how participating in the Port Lincoln Tunarama Festival becomes part of your transit of Australia. It’s how you end up as “the oldest bachelor at a bachelor and spinster ball in Queensland.”

It’s how you find yourself hand-flying your Skylane over the North Pole on instruments, trying to find an altitude that is ice-free but without the need to use oxygen.

It’s the adventure.

You can’t fly that far and that long without some tense moments, and when asked about those, Gannon talks mostly about weather—and not just ice over the North Pole.

“West Africa to Brazil, Cape Verde to Natal, was a very scary flight. One storm after another,” he said. “I took off with 18 hours of fuel, thinking I’d need 14 hours to get there. It took 17 and a half.”

Homebound from the Falkland Islands into 50-knot headwinds was another nail-biter. And whenever he was flying heavily loaded in turbulence, he wondered if the aircraft, named Lucky Lady Too, would hold together.

Weather worries even trumped those long overwater legs in the single-engine airplane, loaded down with up to 22 hours of fuel in tanks that took up most of the cabin space. Those legs didn’t bother him much.

“There are no thermals out there. It’s a calm flight. We all have our fears, but I’m not afraid of flying over water,” Gannon said.

As indicated by her name, Lucky Lady Too (Too as in also) was not the first aircraft in which Gannon globe-hopped. A terse reference on a website to crashing in Kenya in the original Lucky Lady, a Piper Cherokee Six, begged for elaboration.

Not surprisingly, it’s part of a bigger story.

Gannon grew up on an Iowa farm with 13 siblings. He got an agriculture degree, served as a helicopter-borne medic in Vietnam, came home, and went into the construction business. He learned to fly in San Diego in 1992, and then quickly earned an instrument rating, but without any real weather experience. He notes that his introduction to ice came much later, while aloft east of Greenland.

He sold his construction company and took some time off, deciding that an adventure should precede going back to work.

He sold his construction company and took some time off, deciding that an adventure should precede going back to work.

He bought the Cherokee Six from a pilot in Iowa and flew it back to California. Friends from a business course he had completed at Harvard in 1990 were planning a reunion, in Paris. Two days after his instrument-rating checkride, he took off for France.

Then he kept going. He flew all over Europe, the Middle East, across the Red Sea, and into Africa. A case of water poisoning caused by drinking out of a water bottle with a broken seal laid him up for a few days in Nairobi. When finally departing, and still in depleted condition, he didn’t realize until too late that a fueler had put more gas into his ferry tanks than he had ordered.

It was a hot, humid day at the airport, which sits more than 5,000 feet above sea level. Gannon departed on a crosswind runway, rotated too soon, and the Cherokee barely staggered into the air. But it wouldn’t climb. Up ahead an elephant fence awaited “like a giant cheese slicer,” Gannon recalled. The aircraft bounced and the wings and gear separated. When what was left of Lucky Lady came to a stop, Gannon remembered to cut the master switch—a move which he says saved him ‘from coming back in an urn.’

He sold the wreck, and went off to climb Mount Kilimanjaro.

Returning home, Gannon joined a flying club, taking trips into Mexico, and San Francisco, and to the Grand Canyon.

Gannon says that the key to making international flying a smooth operation is to read up on countries’ entry requirements, assemble your paperwork well in advance, and e-mail copies of key documents to yourself—pilot certificate and medical certificates and insurance—so that you can access them from almost anywhere. Have contact information for your destination nation readily available. He even suggests bringing some carbon paper along—in India, officials needed nine copies of a document.

Be patient with the process. It could take hours after you arrive at the airport before you are processed and granted permission to depart. In Mumbai, India, it took from 6 a.m. until noon. Gannon didn’t let that kind of headache spoil the adventure.

Be patient with the process. It could take hours after you arrive at the airport before you are processed and granted permission to depart. In Mumbai, India, it took from 6 a.m. until noon. Gannon didn’t let that kind of headache spoil the adventure.

“If you truly want to see the world, then get over your ideas and prejudices and be happy with the process,” he said.

Gannon’s many letters about the legs of is trip can be seen on the Earthrounders website, and he will host the group’s 2012 reunion in Florida.

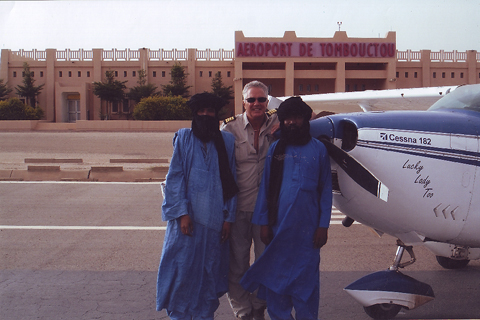

You may never plan to participate, as Gannon did, in the Harry Redford Cattle Drive through the Australian Outback, or fuel your aircraft from a 55-gallon drum mounted on a camel cart (Timbuktu). Still, Gannon hopes you’ll find inspiration in this message on his World Flying Adventure website:

“Hopefully, this site will aid other pilots and adventurers alike with places to go and things to do. And possibly it will encourage you to get at your own adventure. Life is a short flight. If you can do it, do it now!”