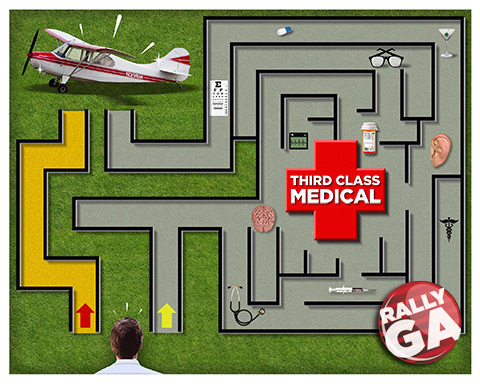

Rally GA: The doctor doesn't need to be in

AOPA and EAA take aim at third class medical

Richard Fox has been flying since his teens, but—like thousands of U.S. pilots—he’s considering shifting to the Light Sport aircraft category because of the potential burden posed by the third class medical examination.

“I’ve got a current medical,” said Fox, 58, of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, who has owned a series of Waco, Pitts, and Stearman biplanes since the 1970s. “But I’m not sure it will be worth the trouble and expense of maintaining it in the future, so I’m planning to switch gears. My next airplane is probably going to be a Cub or a Champ or something else I can legally fly as a sport pilot without a third class medical.”

AOPA has long sought, and petitioned on a number of occasions, to reduce or eliminate the burdens that a requirement for third class medicals impose on pilots, but the FAA has always insisted on having data showing such a move wouldn’t diminish flying safety before making any changes. Now, in a joint effort with the Experimental Aircraft Association, the two organizations are spearheading a major new initiative to give pilots an option—continue to get a third class medical or, in addition to holding a valid driver’s license, complete an online education program on medical self-certification and fly:

• In day, VFR conditions;

• At 10,000 feet or below;

• With a maximum of one passenger;

• In fixed-gear, single-engine aircraft of 180 horsepower or less;

• Aircraft with four seats or less;

• Not for hire.

The data have always shown that glider and balloon pilots, who are not required to have third class medicals, actually have fewer incidents of medical incapacitation than those who do undergo the exams. And now, AOPA and EAA are armed with seven years of experience from the Sport Pilot category.

In all those years, no accidents—zero—were caused by health problems.

“The experience with sport pilots and LSA shows what we’ve long suspected,” said Kristine Hartzell, AOPA manager of regulatory affairs. “The driver’s license medical standard introduced by the FAA demonstrates a basic level of health. Beyond that, pilots are capable of determining whether or not they are fit to fly—and additional educational training on medical topics will enhance that even more.”

AOPA and EAA will ask the FAA for an exemption in early 2012 for the changes. There is no deadline for an FAA response, but the associations will keep pushing.

“Many general aviation pilots like to fly with a friend on good-weather days in simple, single-engine airplanes,” Hartzell said. “Doing away with the third class medical requirement would be a major benefit for them. It would allow them to keep flying safely, and give them the option to remove the burden of the third class medical.”

If the description of the type of flying and kinds of airplanes listed above sounds familiar, that’s no coincidence. The limitations are identical to those for recreational pilots.

The recreational pilot certificate came about in 1988 with the backing of AOPA in an effort to expand the pilot population. But the FAA’s insistence that recreational pilots hold third-class medicals and perform almost all the same training tasks as private pilots—but with many more limitations—prevented the category from living up to its promise. Today, there are only 212 recreational pilots on the FAA registry.

stay informed

AOPA and the Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA) on Sept. 24 unveiled plans that, if successful, could greatly expand the number of pilots who could use the driver's license medical standard currently available only to sport pilots. The two groups are working together to finalize a request to create an exemption allowing pilots flying recreationally to use the driver's license medical standard. In order to ensure and even enhance safety, pilots would be required to complete a comprehensive course on aeromedical factors and self-certification.

Sign up to receive email alerts on the progress of this exemption request, including a notice when you can submit comments to the FAA.

AOPA and EAA propose allowing recreational, private, commercial, and ATP certificate holders to utilize the driver’s license/self-certification medical exemption for flights limited by aircraft size and type of operations. For example, a single-engine aircraft with 180 horsepower or less, four seats or less, and fixed gear in operations limited to day, VFR, and with only one passenger. Instead of a third class medical, pilots would simply take an online course that goes into much greater detail on matters such as flight physiology and identifying medical conditions that could incapacitate pilots, and use that information to assess their fitness to fly prior to each flight. (That course would be available free of charge to all pilots via the Air Safety Institute.)

“The educational program we are proposing will go well beyond the traditional topics of spatial disorientation and hypoxia,” Hartzell said. “It will help pilots identify a variety of medical conditions that could affect flight safety.”

The AOPA/EAA exemption won’t ask for any new FAA rulemaking—a cumbersome process that can take many years to complete. Instead, the associations are seeking an exemption from existing rules.

AOPA and EAA are in the final stages of drafting the exemption, planning to present the strongest case to the FAA. After the exemption is presented to the FAA it is unknown how long the decision process—to approve, deny, or amend—will take.

“The threat of not being able to fly is a big deal to me,” Fox said. “It would mean the end of a part of my life I’ve absolutely loved and shared with my entire family as long as I can remember... Now if you could just make the new rule so that it would allow me to keep flying my [220-horsepower] Stearman, well, that sure would be great.”

Email the author at [email protected].