The view northeast from Anaktuvuk Pass, Alaska, this morning isn't a pilot's dream.

The air is opaque, and the overcast hides a pair of prominent peaks five and 11 miles away. As if for emphasis, a water droplet sits dead center of the camera lens.

To the south and southwest, it's the same story. Fortunately, a pilot planning an arrival wouldn't have to find out the bad news the hard way. A network of aviation cameras—many installed where harsh terrain and harsher weather are the rule—are giving Alaska aviators a nearly real-time glimpse of local conditions, taking some of the uncertainty out of go/no-go decisions when used with aviation routine meteorological reports (METARs) and other information.

Pilots are praising the FAA's Weather Camera Program, and they don't hesitate to share their wishes for its future. That's been gratifying to Walter Combs, the program manager, who says that as the camera initiative expands, it has been meeting its four key metrics of progress.

Overall, the objective is to reduce weather-related aviation accidents, and improve efficiency of operations by sparing pilots the need to “go and take a look” to decide whether a flight can be completed.

“Everyone who flies in Alaska uses a camera now,” Combs said in an interview. “If one goes out of service, I get phone calls and emails from pilots saying, “I use it every day for my operations.”

Commercial pilot Dennis Warth has flown in Alaska since 1980, and he concurs. Other modernization initiatives increase efficiency, but the weather program in Alaska “has a direct relationship to saving lives,” he said.

As of June 2012, there were 179 operational camera sites operating at remote airports, in mountain passes, and at en route locations including the busy corridor between Fairbanks and Anchorage. The newest site became operational June 27 at Grave Point in southeast Alaska. It was the thirteenth site of 24 scheduled for installation this year.

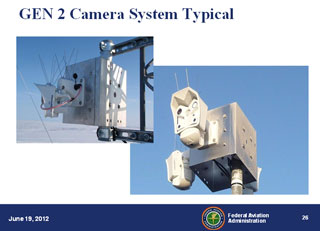

Each installation includes two to four cameras showing views in several directions. When all cameras are deployed—forecast for 2014—the program will operate at 221 locations.

Click a site on a map of Alaska on the program home page to bring up images that are updated every 10 minutes. Next to each current view, a clear-day image of the same scene is provided, with prominent terrain features marked with distance and elevation data.

Each site's page provides details such as latitude and longitude coordinates, and elevation. There's topographic detail, and a sectional chart that traces out the wedge of terrain and airspace captured by the site's cameras. Click a nearby button to view the location's METAR, if available. The images are also available to flight service specialists giving weather briefings

The system is high-tech, but also pretty simple, said Combs. He managed development and installation of the cameras from 2007 to 2011, and became program manager last August.

Designed for harsh exterior conditions, the solar-and-wind-powered cameras are remotely controlled, allowing activation, deactivation, and operation of camera-lens heaters—to melt snow or ice—from a control center. Camera images are transmitted by a satellite communications link.

Warth, who flew de Havilland Beavers, Cessna 206s, and other aircraft for several years for two large floatplane operators in Anchorage, recalls that each morning before flying, “the first thing we'd do is look at the weather cameras.”

With GPS reducing instances of pilots getting lost, Alaska accidents tend to occur on takeoffs, landings, and “hitting granite” after continued VFR flight into adverse weather, he said.

Pilots who use the weather camera images to evaluate flights “are not launching, so there are not events.”

“In terms of saving lives, it's all about the weather in Alaska,” said Warth, an airline transport pilot, flight instructor, and airframe and powerplant mechanic with inspection authorization who now owns a Piper Twin Comanche and a 235-horsepower PA-28 Cherokee.

The cameras have helped reduce the maintenance and fuel costs of Alaska Seaplane Service, said operations director Mike Stedman in a phone interview from Juneau.

Pilots checking the camera images can watch fronts move up the coast, sometimes getting their first alert to weather that isn't conforming to forecast, he said.

Four measures of success

Safety is one of four metrics used to assess the program's performance, Combs said. The safety metric strives for a reduction of accidents below 0.28 per 100,000 operations. Other metrics include improved flight efficiency, as measured by reductions in unnecessary flight time; installing at least 13 cameras per year (24 were added in 2011); and a website availability of at least 98 percent. In 2011 the rate was 99.3 percent, according to FAA data.

Plans include expanding information offerings on the sites' Web pages. In the future, a pilot will be able to place a computer mouse over a site on the program's main map and immediately view a thumbnail of its images.

“You'd start drilling down from there,” Combs said.

The main page for each site will eventually display its METAR and TAF. The program plans to bring Nav Canada images to the site, allowing seamless international flight planning.

Technological triumphs notwithstanding, Mother Nature still sometimes gets the upper hand, occasionally causing a camera to go offline. Then it's time for someone to head out, perhaps trekking to a mountaintop site to scrape snow off a camera's solar panels.

“There are some very remote and rugged sites out there that are difficult to maintain,” Combs said.

While the aviation camera program is a day-to-day resource for Alaska's pilots, Combs hopes that the service will also capture the attention of visiting pilots, some of whom he has observed unprepared for the special demands of flying in the state. (The FAA offers a Fly Alaska Safely Web page providing tips, links to regulatory information, and safety statistics.)

Whether a pilot is an Alaska veteran or a newcomer, Combs expressed satisfaction that the program has become a vital complement to the FAA's 138 automated weather observation systems, 17 flight service stations, and many air-to-ground radio stations.

NextGen improvements in Alaska improve efficiency of operations, but weather data saves lives, said Warth, who urged that more resources be focused on its safety goals.

Stedman offered his wish-list item for the program's future: technology allowing pilots to access the camera images from the cockpit.

“It would be the coup de grace once you can do that,” he said.