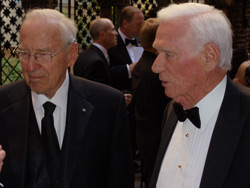

Astronauts and Lindbergh Foundation board members celebrated the organization’s 35th anniversary at the Explorers Club in New York where it was founded in 1977, 50 years after Charles Lindbergh’s solo, nonstop Atlantic Ocean crossing. Left to right, Astronaut Gene Cernan, board member Greg Herrick, Astronaut Jim Lovell, board chairman Larry Williams, board vice chairman David Treinis, and board member Daniel Bennett. Seated: Astronaut Neil Armstrong.

Charles Lindbergh believed in motion. Honoring him with something static, such as a statue, was not a solution, declared Reeve Lindbergh, the aviation pioneer’s youngest daughter with wife Anne Morrow Lindbergh. Reeve Lindbergh made the observation at an intimate dinner celebrating the thirty-fifth anniversary of the launch of the Lindbergh Fund, which today is called the Charles A. and Anne Morrow Lindbergh Foundation.

The event was held May 18 at Manhattan’s Explorers Club, the same location where the foundation was chartered in 1977, nearly 50 years to the day from when Charles Lindbergh left New York in The Spirit of St. Louis to become the first person to fly solo nonstop across the Atlantic Ocean. The event propelled Lucky Lindy to instantaneous worldwide fame, fame that provided a platform from which the couple could showcase their interest in using technology to advance humankind while balancing the needs of the environment. The foundation continues that work today.

As Reeve Lindbergh revealed to the 100 people attending the $1,000-per-plate, black-tie anniversary dinner, her father’s nickname did not come because of his successful Atlantic crossing. Instead, it came from him surviving several aircraft accidents in the years before the crossing. After the crossing, he flew nearly every model of aircraft in existence at the time, she said, often observing from the air the impact that society was having on the environment. “He wanted to continue progress through technology. He was not a Luddite for the environment. He wanted progress and technology and recognized humans’ extraordinary ability to adapt so that we could have both the birds and aircraft—we wouldn’t have to choose.”

Apollo 11 astronaut and first man on the moon, Neil Armstrong, was a co-founder of the foundation, along with Anne Morrow and other aviation luminaries of the time, such as Jimmy Doolittle. Speaking at the New York event, Armstrong reiterated the passion Lindbergh had for balancing progress with the needs of the environment. He along with the two other astronauts speaking at the dinner all had met Charles Lindbergh. Gene Cernan, commander of the Apollo 17 mission and the last man on the moon, spoke of his receipt of the Lindbergh Spirit Award, which is given only every five years. As was Lindbergh’s famed crossing flight, Cernan’s Apollo missions were not the work of individuals, but the result of the efforts of many. “We were the tip of the arrow,” Cernan said, noting that 3,000 to 4,000 people worked on the moon missions. “The award should be given to a nation that gave us the opportunity to do what we did.” A big proponent of manned spaceflight, he wondered aloud whether there was a boy or girl in school today who might one day be the astronaut who launches humans to Mars and beyond.

Jim Lovell, the commander of Apollo 13, which nearly didn’t make it back to Earth after a space accident, was one of the first board members of the foundation. He described the foundation’s series of awards as recognizing those who push technology while balancing the needs of the Earth.

Apollo 13 Commander Jim Lovell and Apollo 17 Commander Gene Cernan were among the space pioneers addressing the crowd celebrating the 35th anniversary of the Lindbergh Foundation May 18.

Apollo 13 Commander Jim Lovell and Apollo 17 Commander Gene Cernan were among the space pioneers addressing the crowd celebrating the 35th anniversary of the Lindbergh Foundation May 18.

Like thousands of young boys in the 1930s, Lovell was inspired by Lindbergh. “We all wanted to be pilots,” he said, noting that Lindbergh’s passion for technology led him to be involved in the development of the first rockets—technology that ultimately led to the Apollo missions. Lindbergh was also instrumental in the development of biomedical equipment and other cutting-edge technology while at the same time studying people in secluded jungles in Southeast Asia with access to no technology. In fact, Lindbergh was deep in the jungle when he happened to hear about the troubled Apollo 13 flight and the attempt to safely return it to Earth. As soon as the space capsule splashed down, Lindbergh sent a hand-written letter to Lovell. Lovell read the letter to those attending the anniversary dinner. The letter congratulated Lovell on his success in returning safely to the planet and reminded him about the perils that face pioneers.

Foundation chairman Larry Williams, CEO of BRS Aerospace, which makes aircraft parachutes, said the foundation continues to reward and recognize pioneers through its series of grants and awards. Grants are made for projects in a series of categories, including aviation/aerospace, and are given in amounts up to $10,580, the cost to build The Spirit of St. Louis. More than $3 million in grants have been given since the foundation’s inception. Funding limitations have caused the foundation to not present any grants in 2012, although grants are expected to resume in 2013.

Meanwhile, the foundation’s Aviation Green Alliance is growing with support from major aviation companies. Aviation Green was established to address the pressing environmental issues facing aviation. The alliance attempts to establish ways that members can share information and successes in dealing with environmental issues and funds grants to help develop new technology to reduce the environmental impact of aviation.